Camano Island is the second largest of the dozens of islands in the northern Puget Sound that were formed by glacial deposits during the last Ice Age. Encompassing about 40 square miles, the island is 16 miles long from north to south and has about 50 miles of shoreline. Several Coast Salish tribes shared the island until non-Native settlers arrived in the 1850s to operate timber and shipbuilding businesses at Utsalady Bay. Camano Island became a vacation destination in the twentieth century and remains a popular spot for recreation and relaxation. No town has been incorporated on the island, but the population has increased steadily, from 1,395 in 1960 to more than 17,000 in 2020.

Exploration and Mapping

Camano Island is separated from the mainland on its eastern shore by Port Susan Davis Slough, a waterway between Skagit Bay and Port Susan at the mount of the Stillaguamish River. In June 1792, British Captain George Vancouver led a mapping and charting expedition of Puget Sound that included the first observations of Camano. Piloting the sloop Discovery and accompanied by the armed tender Chatham, Vancouver proceeded about six miles up what Vancouver named Port Susan. But when the crew charged with taking soundings failed to notice the shallowness of the waters, the Chatham grounded, stopping their progress in approaching the mainland. Vancouver decided to turn around, and thus never recognized Camano as an island. It wasn’t until the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842 that it was so identified and given the name McDonough’s Island. The name of the passage between Camano and Whidbey Island that Vancouver referred to as Port Gardner was changed to Saratoga Passage. Point Allen at the south end of Camano became known as Camano Head. The British renamed the island in 1847 for Don Jacinto Caamano, who explored Nootka Sound in 1792 but never sailed southward to the Puget Sound or saw his namesake.

The Kikiallus band of Coast Salish Indians kept winter villages on the island at places now known as Utsalady and Madrona, and in the lower section south of Camano City. The Snohomish band had seasonal camps from Elger Bay south and around the east side of the island. Camano Head was the site of a deadly landslide, thought to have occurred in the 1830s, that killed many Indians who were camped there. Accounts by early non-Native settlers recall Northern Indians traveling through in their West Coast canoes to work as hop pickers in south Puget Sound.

Across Saratoga Passage on Whidbey Island, non-Native settlers arrived at Penn Cove in the early 1850s. They soon recognized the promise of Utsalady Bay as a sheltered deep-water location for timber. The name Utsalady was unusual, and its origin has been debated by researchers. According to Robert Hitchman’s Place Names of Washington, Utsalady is a Chinook jargon term "Ollallie," thought to mean "place of berries" (Hitchman). Secondary sources and newspaper accounts in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries primarily repeat the berries story, which was mentioned by Puget Mill Company executive E. G. Ames in his 1884 typewritten "History of Utsalady, Washington." There is also the local account of an unnamed Utsalady Scotch father who is claimed to have answered the question of whether his newborn child was a girl or boy: "Uts-a-laddy."

Activity at Utsalady

When Washington Territory was created out of Oregon Territory in 1853, Lawrence Grennan and partners James Thompson and Marshall Campbell established a spar camp at Utsalady Point on the north end of Camano Island. Cutting 200-foot trees, it took them two days or longer to land their timber near the shore to load onto waiting tall ships. Grennan chose Utsalady because the bay was sheltered and deep enough for the tall ships. With the permission and assistance of Native American Kikiallus men, the first load of Douglas fir spars was logged from Utsalady by Thomas Cranney, who by then had bought an interest in the venture. The Kikiallus gave permission to Grennan and Cranney, a storekeeper who lived at Coveland on Whidbey Island, to take the tall trees along the shoreline of Utsalady Bay for spars, and were hired to help.

Grennan went to San Francisco to purchase a steam engine, boiler, and saws to start a mill at Utsalady Point. On the return trip to Puget Sound the machinery had to be thrown overboard when the ship met rough seas passing the Columbia Bar. In 1855, spars from Puget Sound were shipped to England and France by Captain James Henry Swift of Whidbey Island, the first of three such voyages. Thompson and Campbell dissolved their interest in the earliest camp in 1856, leaving Grennan and Cranney to form a new partnership with a mill. In the meantime, in 1855 the Treaty of Point Elliott was arranged, and the Kikiallus chief Sd-zo-mahtl was among those who signed it.

When prices for lumber rose in 1856, the Grennan and Cranney Company formed. It built the 600-by-100-foot mill building with its boiler engine and vertical saws in the winter of 1857. The mill began operating in 1858 and paid off a mortgage that financed the construction in 1860 with a shipment to Shanghai. The mill was built at the eastern shoreline of Utsalady Point and produced up to 64,000 board feet per day. Cranney continued the business despite an 1859 setback due to falling lumber prices, when he again had to mortgage the mill.

The mill attracted workers and settlers to the area after the Fraser River gold rush in 1858. Grennan and Cranney established a school, a Masonic Hall, and a store, and there were several houses built to accommodate the workers and their families. Mill workers' cottages were built behind and up the logged-off hillside at Utsalady Point. A two-story granary was built to hold grain from Skagit River farms. The noise from machinery, including a 175-foot-long slab conveyor, was said to be tremendous, and smoke from the fires was always present. In August 1866, a flagstaff 150 feet long was loaded to be used in Paris at the 1867 Exposition. The 1867 Pacific Coast Business Directory advertised "lumber and spars shipped to all parts of the world" from Camano Island.

There was an active shipyard at Utsalady where the steamer J. B. Libby was built in 1862. It was a 70-ton sidewheeler that was launched at Utsalady and used by different owners until 1865. Beginning about that time she began to carry passengers and mail two times a week between Seattle, Coupeville, Utsalady, Swinomish (La Conner), and Whatcom. Between 1861 and 1873, nine vessels of various types were built at Utsalady.

In 1869, Cranney’s original partner, Lawrence Grennan, died while on a business trip to California. Cranney continued operations along with business partner Colin Chisholm and silent partner Elizabeth Grennan. Then on November 4, 1875, the American sidewheel passenger steamship SS Pacific foundered after a collision south of Cape Flattery with a loss of 275 lives. Struck by the S/V Orpheus, she went down in a few minutes. Only two survived. This was a well-documented and tragic event on many levels in the Puget Sound, but little was mentioned of the resulting loss to Cranney, whose partner Chisholm was one of the passengers on the SS Pacific. "As manager of the mill, Mr. Colin Chisholm, was going south to settle bills for the sawmill and for the stores, shipyard and others" (Prasse, 15).

With Chisholm dead, Cranney filed for bankruptcy, and so a new era began at the Utsalady Mill. The Puget Mill Company purchased the mill and mill site for $32,000 in March 1876, and Cranney moved back to Whidbey Island in 1877. For the next 15 years, Cyrus Walker modernized and managed the mill, though he usually worked from the Puget Mill headquarters at Port Gamble. According to E. G. Ames, the mill could cut logs up to 6 feet in diameter and up to 75 feet long, had a capacity of 75,000 feet per day, and employed about 45 men. It also had a lath mill and could produce 10,000 lath per day with a crew of four. The mill at Utsalady operated for almost 30 years before closing in 1891, the same year the railroad arrived in Stanwood. This permanent closure was unanticipated, but Utsalady was an inconvenient port for access to the Strait of Juan de Fuca and international trade. The Panic of 1893 caused a depression that the region did not rise above until the Klondike Gold Rush in 1898. The mill building stood idle, and the machinery was removed to other Puget Mill sites. In April 1897, a fire from a stovepipe destroyed at least 15 houses, though the mill building was saved.

By 1900 there were 460 people counted in the census on Camano Island. A fire took the hotel in 1906, and in 1916 the Utsalady mill building was taken down. Yet farm families remained in the area, and women, led by Constance Olson, formed the Utsalady Ladies Aid, raising funds for a variety of causes, and built a new building in 1923. That building is now on the National Register of Historic Places and remains the heart of the Utsalady community.

The Utsalady Post Office remained active until 1910. Among those on the island were Norwegian immigrants Sivert Johnson, Nels P. Leque, O. B. Iverson, and John Einarson, who had established farms on the north end of the island in the 1870s. The local Masonic Hall was established in 1872. It was called the F. & A. M. Camanio Lodge No. 19 in reference to the Spanish pronunciation of the name of the explorer Don Jacinto Caamano. The order moved to Stanwood in 1890 because the Stanwood members had difficulty getting to meetings on the island; many of them had worked in the mill before they moved to Stanwood or to farms in the Stillaguamish Valley. By 1903, the Stanwood Lumber Company incorporated at the mouth of the Stillaguamish; a few of the Utsalady employees worked there or at nearby shingle mills.

Villages, New and Old

Native American encampments and villages began to disappear as properties were built upon and Indigenous populations diminished from disease and relocations to reservations. Primary locations of villages were Utsalady and Madrona, with smaller summer camps at Indian Beach, Camano Head, and Juniper Beach, though shoreline encampments were present at any point from time to time. A few Native Americans returned to Camano City and Indian Beach to dig clams until the 1930s. Many of the non-Native men who came to Camano married Kikiallus women; among them were Marshall Campbell and John O’Brien (d. 1908). O’Brien sold a section of his land at what became the locality Terry’s Corner for the first cemetery on Camano, now called Pioneer Cemetery. It was established on a wetland, so a second cemetery was built by the Camano Lutheran Church on the uplands to the southwest in 1921.

In 1902, the Camano Commercial Company was incorporated by James and Andrew Esary, and in 1904 the Camano Land & Lumber Company was established with James Esary and Alpheus Byers listed on the incorporation papers. They began logging various tracts from the west side of the island and built the schoolhouse at Camano City in about 1904. There was also a school at Livingston Bay, established in 1884. Its building was replaced twice; the second school burned down in about 1913, and the third operated until 1937, when schoolchildren began to be bussed to Stanwood. Other schools were located at Mabana, Rocky Point, Elger Bay, and near Triangle Cove.

The other large logging operation on the west side of the island was operated by Dominick Cavelero. In the early years Cavalero used oxen to haul logs to the east side of the island from the ridge. His logging camp had a large cook house, bunk house, and a long log chute extending to Port Susan. He also owned and operated the shingle mill on Driftwood shores with Nels Konnerup.

Logging activity on the south end began about 1911 when Nils Anderson began operations and built a 900-foot wharf at a place he platted as Mabana. About that time a small store with the post office was established. In 1916, perhaps as a result of Anderson’s influence as a county commissioner, a wagon road was put in as far as Mabana. Sterling Barnum, also an early commissioner, had a road built to his farm at Barnum Point. As many as 20 logging camps hauled timber out, leaving immense stumps and acres of slash in their wake that led to platting and selling lots.

When Camano Island's few farmers needed access to the mainland, they went by boat or the ferry crossing, which could carry wagons until 1909, when a bridge across the Stillaguamish River signaled the transition from water to motor vehicle and connected Camano Island to Stanwood. After roads were paved, it was only a two-hour drive between Camano Island and Coupeville, the Island County seat on Whidbey Island. The coming of the bridge and the automobile resulted in a collaboration with Snohomish County for school and library support; residents used Stanwood as their commercial district. There never has been an incorporated town on Camano Island.

Farming on the island was small scale with milk cows and orchards, though there are still a few farms with fields large enough to hay and manage livestock. The founding family descendants still own the Kristoferson Farm, which dates to 1912. The extensive Danielson Farm (1917) visible from State Route 532 provides a sweeping visit of the pastures and hay fields with the mountain ranges in the distance. Other farms included a 15-acre holly farm (1956) that is now part of Island County Barnum Point Park, once also a farm. In 1938, the Williams Turkey farm was established, selling turkeys to Seattle or locally.

Making Connections

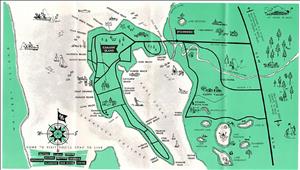

As early as 1911, when the population was 678, attempts were made to promote Camano Island as a destination. Maps from the period reference Camano City, a dot on the west side of the island that was never an incorporated town, much less a city, though the name has always held. Before the county road was built over the creek north of the schoolhouse at Camano City, early residents had to drive down to the beach and back up the other side of the creek to proceed south. But the road to Mabana from Camano City wasn’t to be until 20 years later. The schoolhouse has survived as a community center operated by the fire auxiliary and is now on the Washington State Historical Register. It is operated by the Camano Schoolhouse Foundation.

In 1915, the Utsalady-Oak Harbor Ferry began operating between Whidbey and Camano. A new ferry, the Acorn, made its first run in 1924 and continued until 1936, a year after the Deception Pass Bridge was completed. Many attempts were made to establish another ferry run in the 1960s through 1982, but a ferry service has never materialized to connect with the county seat.

Beginning in the 1920s, several people who owned land on the shorelines started resorts and rented boats to vacationers. Camano Island was promoted as the "Island You Could Drive To." Shoreline property continued to be divided up into small shoreline lots and cabins were sold to those in cities who could afford a second property. The interior remained open space with a few scattered small farms. The population was still small, ranging from 678 in 1910, to 910 in 1920, and 679 in 1930. This made the island’s shorelines convenient landing places for bootleggers and moonshiners during Prohibition. Law enforcement kept busy monitoring isolated coves and beaches for deliveries.

Up until the early 1930s, steamers served Utsalady, Camano City, and Mabana on Saratoga Passage, where post offices, small stores, schools, and hotels operated. Camano City and Mabana had long docks enabling better access at low tides. Over the years schedules varied, and the Mabana stops, which connected with Everett, were more oriented to South Whidbey than Stanwood. These services could vary depending on the economy, weather, tides, and current logging activity.

In 1926, Nils Anderson sold 66 feet of shoreline, which included the Mabana dock, for $500 to the Port of Mabana for public access. According to Port of Mabana minutes from 1934, repairs were still being made to the dock, funded through residents’ subscriptions. In 1935, the port commission levied a tax for maintenance, which continued until 1942, when the commissioners voted to discontinue dock maintenance and the county took over the road. The Port of Mabana still exists, continuing to provide among the very few public access points on the island. A Port of Camano was established in 1925, though it never became active. In May 1981, a controversial vote to expand the Mabana port to an island-wide port district failed resoundingly.

In response to the long distance to the county seat and lack of representation in local government, every few years citizens have explored ideas of annexing to Snohomish County, or tried to incorporate the whole island. All attempts have failed when put to a vote. They also made later efforts to convert the whole island to a city, as Bainbridge has. But that was repeatedly voted down.

Resort Era

After the Camano Commercial Company dissolved in 1927, the dreams for a Camano City as a town were long past. The small year-round stream, Chapman Creek, runs under the road there and down from the gully to the east. In 1926 Camano Land and Lumber Company sold the hotel and adjoining lots, and it has since served as a local landmark on Camano Island called the Camano Island Lodge and had a succession of owners who operated primarily as a restaurant and hotel. In 1960 it became the Camano Rest Home for senior citizens with capacity for 20 guests. The Rest Home owner sold it again in 1995 and 2008. In 1959 a restaurant opened on SR 532 as the Camano Island Inn; it was said to be the only restaurant on Camano at the time.

Beginning in the 1920s, the automobile, "paid" vacations, and perhaps a little more disposable income for the average worker allowed people to get away to camp, hunt, fish, swim, hike and picnic farther away from home. For those in Seattle and Everett, Stanwood and Camano Island were popular destinations.

The early 1930s brought road improvements from Tulalip to Stanwood, with the idea that it would promote a tourism economy. On Camano Island in the late 1920s, summer cabins began to be built along the most accessible beaches. "Auto parks" with tent spaces, community kitchens, tables, and benches were also created. Resorts with cabins were established promoting their scenic views, fishing, clam digging, crabbing, picnicking, and hunting. Most had a small store and a gas pump associated with them. Many fishing derbies were sponsored; the larger ones offered boats and motors and a way to launch a boat. On Camano Island, most were located on the west side of the island on Saratoga Passage. Some of the resorts were well-established, others were of a more temporary nature and went through many owners.

Beginning in the 1930s, people apparently preferred and could afford to buy their own cottages. With the introduction of bigger boat motors and the ability of people to trailer their boats, vacationers no longer needed many of the services the resorts could offer. Gradually, the economy of Camano, in addition to its small farms and logging operations, became focused on real estate rather than resorts. Many of those who enjoyed the resorts most certainly bought retirement property or investment property. The eventual diminishment of salmon populations brought the fishing derbies to an end.

The Camano Commercial Association was established in 1947 and became the Camano Island Chamber of Commerce in 1957. The local retail economy was limited to a few stores that provided gas and groceries to campers and cabin owners. There was Huntington’s Store established in 1951, and Elger Bay Store established about 1953. There was an Utsalady Store aka Utsalady Trading Post. Camano Plaza started in about 1964, featuring a "superette," and "automatic laundry" and dry cleaning with plans for a restaurant and hair stylist. It is as of 2023 the only full-service grocery on the island. The And Tyee Store, farthest south, opened in the 1970s and closed in 2021. Restaurants and cafes came and went.

After World War II, news articles reported on the establishments of a resort-owners association and commercial clubs to help promote tourism. Among the earliest resorts was the Madrona Beach Resort, established by Henning Sandberg in about 1926. In 1955, Clinton Parker took over and established a rural postal station, which was discontinued in 1969. There were no parks and little access to the privately owned shorelines and beach cabin communities, so in 1949 the local South Camano Grange in collaboration with Stanwood residents lobbied the State to establish Camano Island State Park. It took similar citizen advocacy to establish Cama Beach State Park in the 1990s with the purchase of the largest of the remaining resorts, Cama Beach Resort.

Neighborhoods

The development of planned neighborhoods on Camano began at the end of World War II, when logged-off properties were developed. Rocky Point and Maple Grove were early neighborhoods. Dan Garrison, son of Porter Garrison, a colorful logger at Camano City, converted the Cavalero log dump landing and surrounding hillside into the expansive Country Club development, with lots platted along the eastern side of the island. It is among the largest of the early developments, though many hillsides on the upper ridges are now sprawling with large homes on circuitous streets.

Social services for retirees began at the Camwood Senior Center, which provided nutrition programs and other outreach services. In 1973, Senior Services of Island County was formed, and in 1978 until 2000 these services were located at the County Multi Purpose building. It provided a successful Thrift store that raised significant funds. Its first location was at the Camano Yacht Club. In 2001, a new Senior and Community Center building was completed on the north end of the island with beautiful artworks throughout.

Into the Future

Since the 1980s a new generation of retirees and young people have inspired new types of activities on the island. In 1990 Island County Extension established WSU Beachwatchers for environmental adult education regarding water quality of the Puget Sound now known as Sound Water Stewards and Shore Stewards. A new parks organization grew out of the advocacy efforts of volunteers for the Cama Beach State Park. Friends of Camano Island Parks serves as a critical volunteer support group for maintaining and advocating for parks, recreational water access, and preservation of open space and shorelines. Many of them now celebrate local history at the English Boom Trail, Iverson Trail Preserve, and Barnum Point County Park, all providing dramatic views of the surrounding mountain ranges.

There always were artists on the island, but in 1999 the first annual Mother’s Day Studio Art tour took place, featuring many artists who had recently been attracted to affordable living on the Island. Among the many Chamber of Commerce efforts to promote the island, several artists joined and decided to help build a new visitor center with updated signage. In May 2000 Camano Island celebrated the replacement of a small visitor center at Terry’s Corner with an architect-designed metal building featuring art glass and sculptures and paintings to begin a new century on the island.