Although dense primeval forest covered much of Whidbey Island, there were also fertile prairies that for centuries were used and maintained by Indigenous people. Most were on Central Whidbey, the ancestral home of the Whidbey Island Skagit tribe. In the mid-1800s the first non-Native settlers arrived, and after some initial hostility the Skagits largely tolerated their presence, only to be repaid by swift and utter dispossession. Farming, trade, and small industries such as boatbuilding sustained the early settlers, while logging eventually came to dominate the island economy. As areas were logged, new settlements arose, primarily in South Whidbey. In 1901 the army's Fort Casey opened on the island’s west shore. Whidbey’s population continued to grow modestly for several more decades, then took a large leap in 1942 when Naval Air Station Whidbey Island (NASWI) was commissioned at Oak Harbor. In 1978 Congress created Ebey's Landing National Historical Reserve, the first, and still only, historical reserve in the country. As of 2022 Whidbey Island remained predominately rural, with two incorporated cities and one incorporated town, a vibrant arts and cultural scene, and an economy buoyed by the island's seemingly irresistible allure for day-tripping mainlanders.

A Few Fast Facts

Whidbey is the largest of eight islands in Island County and one of only two that are populated, the other being Camano. The fourth-longest saltwater island in the contiguous United States, it measures about 41 miles from tip to tip (although there is a remarkable discrepancy among sources), with about 148 miles of convoluted shoreline (another disputed measurement). Estimates of its area also vary widely. Broader land masses at both ends are connected by a narrow central section, not much more than a mile wide at Penn Cove and Holmes Harbor. Most of the land is agricultural or undeveloped.

Whidbey has suffered a number of variant spellings, including Whidby, Whidby's, Whitby, and Whitby's. There are three regions -- North, Central, and South -- which have no precise demarcations and are more notional than actual. The terrain comprises rolling hills, forests, prairies, bluffs, and marshes. There are four primary freshwater lakes -- Deer, Lone, Goss, and Cranberry. Crockett Lake, the largest on the island, is a brackish wetland preserve near the shore of Admiralty Bay. There are no rivers, but abundant streams. The rain shadow of the Olympic Mountains limits Central Whidbey's average annual rainfall to 18 inches, about half that of South Whidbey. Average winter temperatures are in the high 30s and the high 60s in summer.

The island's estimated population in 2022 was almost 66,000. With the exception of those in its three incorporated municipalities, most island residents live in rural settings or small, unincorporated communities. Its most historic town is Coupeville, the Island County seat, and much of Whidbey's artistic and cultural life is centered on Langley to the south. Oak Harbor is the undisputed commercial center, much of it in the service of active-duty military personnel and civilian employees of NASWI. The largest private-sector employer, Nichols Brothers Boat Builders in Freeland, builds ferries, fishing vessels, yachts, and other watercraft. In 2018, the last full pre-pandemic year, tourism revenues for Island County were nearly $850 million, most of it spent on Whidbey.

Whidbey Island is served by two ferry routes, between Mukilteo and Clinton and Port Townsend to near Coupeville. Since 1935 it has also been accessible via State Route 20 and the Deception Pass and Canoe Pass bridges at its northern tip.

Out of the Ice

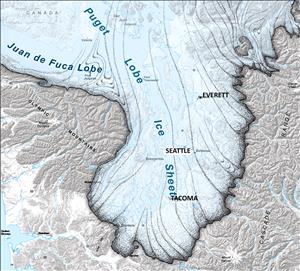

Over the 2.6 million years of the Pleistocene Epoch, which ended about 11,500 years ago, there were up to 20 cycles when massive glaciers, thousands of feet deep, advanced, retreated, and advanced again over much of the globe. At the peak of the most recent Ice Age, a tongue of the vast Cordilleran ice sheet extended as far south as Thurston County. (Note: For clarity, contemporary place names are used throughout.) Called the Puget Lobe, it buried north Puget Sound under nearly a mile of ice, its massive weight depressing the Earth's crust by hundreds of feet.

The lobe began a rapid retreat about 16,000 years ago. Glacial meltwater raised sea levels worldwide, but the Pacific Ocean was blocked from entering Puget Sound by the still ice-locked Strait of Juan de Fuca. South of that, the Puget Lobe’s disappearance revealed a gouged, scoured, and barren landscape -- the Puget Lowland. Unburdened of ice, the Earth's crust began to rebound, and freshwater lakes, mostly meltwater, appeared. When the Strait of Juan de Fuca became ice-free, the Pacific Ocean flooded in, displacing the fresh water and filling Puget Sound. As the rebound continued and sea levels dropped, Whidbey Island emerged as several smaller landforms coalesced.

A Changing World

Life returned over thousands of years, and most of Whidbey became blanketed by thick forests. But, primarily in the central section, scattered grassy lowlands developed where gravelly glacial till from the Puget Lobe mixed with the organic remains of life-forms -- plants and animals -- that thrived between earlier glaciations. These fertile prairies hosted camas roots, nettles, bracken ferns, and other food plants used by humans, who first arrived on Whidbey more than 10,000 years ago. At some later point, they learned to maintain the prairies by intentional burning that destroyed invasive trees and shrubs and further enriched the soil.

Most sources agree that in recorded time only two Coast Salish tribes maintained permanent villages on Whidbey. The Whidbey Island Skagits, the most populous division of the Lower Skagits, had five villages in their realm, which encompassed almost all of the island north of Holmes Harbor. In winter they lived in large, multifamily longhouses, with many dispersing in spring to temporary encampments near rich food-gathering sites. A smaller contingent of the tribe dwelt near the delta of the Skagit River on the mainland.

The Snohomish tribe had two shoreside villages on heavily forested South Whidbey, at Cultus Bay and Brown's Point (now Sandy Point). According to at least one source, there was a third village on the west coast at Willow Point (now Bush Point), with "a Potlatch house, three long houses [sic], a few private dwellings and a cemetery" ("Bush Point). A more aggressive group, the S'Klallam from the Kitsap Peninsula, held a small enclave on the western shore in Skagit territory, but it was not always inhabited. Other Puget Sound tribes came frequently to Whidbey to gather plants, hunt, confer, and celebrate potlatches, but maintained no continuous presence.

This life would not last. Since the 1700s, epidemic diseases brought by explorers, traders, sailors, and non-Native settlers had repeatedly scythed through Native American populations across the land. There is no accurate accounting of the toll taken on Whidbey Island, but there was no escape. Then, in the early 1850s, the first Euro-American settlers came ashore, drawn by the same fertile prairies that sustained the Skagits. Within little more than a half-decade, 10,000 years of indigenous habitation came to an end.

First Contact: Joseph Whidbey

On May 30, 1792, Lieutenant Joseph Whidbey (1757-1833) of the British exploring ship HMS Discovery came ashore near Penn Cove, believing it to be the mainland. His party encountered a friendly Native group, almost certainly Skagits. Their curious wonder at Whidbey's pale skin indicated that he and his men were the first white people they had seen, but a few metal artifacts and smallpox scarring suggested that they already had been touched, at least indirectly, by foreign technology and disease.

Whidbey next sailed north to Deception Pass, where he discovered that his earlier landing place was part of a large island. The Discovery's captain, George Vancouver (1757-1798), gave it Whidbey's name, writing in his journal that "The Country ... is, according to Mr. Whidbey's representation, the finest we had yet met with, notwithstanding the very pleasing appearance of many others ... The number of its inhabitants he estimated at about six hundred ..." (A Voyage of Discovery ...).

Men in Black

After the Discovery sailed on, Whidbey's Native people went unmolested by white outsiders for nearly 50 years. In 1838, Catholic priests Francois Norbert Blanchet (1795-1883) and Modest Demers (1809-1871) arrived at Fort Vancouver to minister to European settlers and convert the Native population. Their writ covered a huge territory, so they trained catechists (lay teaching assistants) -- first settlers, then tribal leaders -- to help spread the gospel.

Tsalakum, a Whidbey Island chief whom Blanchet identified as a "Skekowmish" or "Sowkamish" ("Exploring 10,000 Years ..."), was perhaps the first Native catechist. In spring 1839 he traveled more than 100 miles to Blanchet's Cowlitz Prairie mission, where he took well to the preaching of the "black robes." He asked Blanchet to visit the island, and when the priest did so a year later he was gratified to find that Tsalakum's people knew the sign of the cross and could sing simple hymns in Chinook trading jargon. Other island Natives soon arrived, including a group of Skagits led by the widely respected, perhaps paramount, Chief Snakelum (d. 1852). A few days later, a 24-foot wooden cross was built and raised by the tribesmen. Despite such overt signs of faith, many "converts" did not embrace Christianity exclusively, but simply incorporated biblical stories and personalities into their age-old, spirit-filled belief system.

In July 1841 the United States Exploring Expedition, led by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes (1798-1877), passed by Whidbey Island and noted the presence of the mission at Penn Cove. Wilkes wrote in his account that the island was "more thickly peopled" and the tribe "more advanced than any others" he had yet encountered (Wilkes, 41). But by 1847 the mission had been abandoned and the priests gone, "owing to the turbulent disposition of the Indians" (Kane, 227).

Off to a Bad Start

In 1848 Thomas W. Glasgow; his Native wife, Julia (1830-1857), and Antonio Rabbeson (1825-1891) canoed north from Tumwater to a prairie plot on the west side of Whidbey Island that Glasgow had claimed the year before. Shortly after their arrival, members of almost every Puget Sound tribe and band arrived at Penn Cove to have what Rabbeson called "a grand hunt and big talk" ("On Puget Sound ..."). He estimated, perhaps with some exaggeration, that they numbered about 8,000.

The hunt went very well, but the talk did not, at least for the settlers. Julia's father, Patkanim (1815-1858), the wily and volatile chief of the Snoqualmie and allied tribes, called for an attack on the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Nisqually "to kill or drive the King George men (as the English were then called) out of the country" ("On Puget Sound ..."). Warned by Julia that the chief planned to kill them first, Glasgow and Rabbeson stole a canoe that night and left, never to return. (In May 1848 Patkanim did attack Fort Nisqually, unsuccessfully. Bowing to the inevitable, he allied with the American military during the Treaty Wars of the mid-1850s.)

Coming to Stay

At the urging of his friend Samuel Crockett (1820-1903), in the spring of 1850 Isaac Neff Ebey (1818-1857) left Olympia (which he is credited with naming) to explore Puget Sound by canoe. Drawn by Whidbey Island's agricultural potential, Ebey became its first successful white settler. More would arrive very soon. Most Native residents, if not enthusiastic, were by then not openly hostile, in part because they hoped the settlers' guns might protect them from slaving and plundering raids by rapacious tribes from Canada.

In September 1850 Congress passed the Donation Land Claim Act (DLCA), which granted 320 acres of public land (with conditions) to white or "half-breed Indian" (DLCA, sec. 4) males who arrived or would arrive in Oregon Territory before December 1 of that year. If married, an additional 320 acres could be claimed in the name of the spouse. On October 15, 1850, Ebey filed for 640 acres (one square mile) of prairie land on the west side of the island, including Glasgow's abandoned claim. His wife, Rebecca (1823-1853), and their two sons arrived from Missouri in 1852 with her three brothers.

Less than three months after Ebey, three men filed donation claims on Whidbey after failing to find their fortunes in the California Gold Rush. Zakarias Martin Taftezon (1821-1901), Ulrich Freund (1821-1870), and Clement W. Sumner (1818-1891) took passage to Oregon Territory in 1850, hired Native canoes, and on January 4, 1851, took up adjacent donation claims on prairie land between two hills on the north shore of Oak Harbor. There followed two Irishmen, Thomas Maylor Sr. (1823-1898) and his brother Samuel (1821-1896), who settled on the peninsula that separates Oak Harbor from Crescent Harbor to the east. In the summer of 1851, William Wallace and his wife, Rufinda, were first to claim on Crescent Harbor. Their daughter, Paulowna, was the first white child born on Whidbey. In 1855 the Wallaces started the island's first formal school, and William is credited with shipping over its first horse.

Also in 1851, Dr. Richard Lansdale (1810-1897), after naming Oak Harbor and Crescent Harbor, moved south, claimed 320 acres near the head of Penn Cove, and started the village of Coveland. On January 6, 1853, less than three months before Washington Territory was created, the Oregon Territorial Legislature created a vast Island County, which included present-day San Juan, Skagit, Snohomish, and Whatcom counties, with Coveland named the county seat and Samuel Crockett's brother Hugh (1829-1900) appointed sheriff. Among the most prominent early arrivals to Penn Cove was Thomas Coupe (1818-1875), the only captain to successfully sail a square-rigged ship through Deception Pass. He settled there in 1852 and eventually claimed 320 acres. His wife, Maria, joined him in 1853. Their land became part of the town of Coupeville, which in 1881 would replace Coveland (now called San de Fuca) as county seat.

In 1854 Rebecca Ebey delivered a daughter, Harriet, but died four months later. Early the previous year, she had taken an informal census of Whidbey's non-Native population -- six families, 15 young children, and 18 bachelors and "youths" (Kellogg, 25). By the time the DLCA expired in December 1855, 29 claims had been filed for land on or bordering prairies near Penn Cove, including by several Crocketts and Ebey's parents, Jacob (1793-1862) and Sarah (1796-1859), who arrived in 1854 with three of Isaac's adult siblings. In January 1856 Isaac Ebey married a widow, but she was soon widowed again. On August 11, 1857, a band of Native warriors from north of the border killed Ebey at his home, taking away his head as a trophy.

A World Lost

On January 22, 1855, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862) concluded the Point Elliott Treaty council at Mukilteo. Representatives of more than 23 tribes attended. The Skagits had no recognized chief, so Stevens appointed one -- Goliah, described later as a man "of humble birth" in a largely heirarchical society who previously "had negligible importance to the natives" (Harmon, 101). Goliah is often identified as a Lower Skagit, but only the term "Skagit" appears in the treaty. The Whidbey Skagits had no say in Goliah's appointment, and his name does not appear in any historical accounts of the tribe that predate the council. Nonetheless, he and 18 Stevens-appointed subchiefs put their X marks on the treaty as "Skagit." None of the estimated 300 then-remaining Whidbey Skagits are known to have attended the council, and no provision was made for an island reservation, although their ancestral lands exceeded 50,000 acres and could easily accommodate one.

The Whidbey Skagits had lived on the island since as early as 1300 BCE. In far less than a decade after Isaac Ebey came ashore, they lost the land that had shaped and sustained their culture for centuries. The Point Elliott Treaty established the Lummi, Suquamish, Swinomish, and Tulalip reservations. Most Whidbey Skagits ended up on the Swinomish Reservation on the southeast portion of Fidalgo Island, others on the Tulalip Reservation. It appears from photographs that a potlatch house stood for many years thereafter, probably at Penn Cove, but the very few Skagits who remained on the island were for the most part regarded with affectionate condescension by the usurpers.

Exploiting the Forests

Simple survival was the priority for the island's first white settlers, but commercial exploitation of its natural resources lagged not far behind. The 1860 census counted 292 non-Natives in Island County, and 15,381 acres had been claimed on Whidbey, "nearly all of them on or bordering the prairies" (White, 38). Only Penn Cove's Coupeville and Coveland could plausibly claim to be villages. In 1861 the Washington Territorial Legislature created Snohomish County from the last mainland portion of Island County. All the best farmland had by then been claimed on Whidbey, and population growth slowed.

As the prairies were farmed and the necessities of life secured, interest turned to the island's most plentiful saleable resource -- its thick forests. Conifers, primarily fir, were the dominant species, but thousands of Garry oaks, useful for ship building, flourished in the savannah-like ecosystem around aptly named Oak Harbor. Low-level commercial logging began on Whidbey in the 1850s, and over the ensuing decades it would become the largest component of the island's economy. Federal law prohibited the sale of public land for any purpose before it was surveyed, and Whidbey had not been. Until it was, loggers simply ignored the restriction and harvested trees at will, with much of the labor done by Native workers. As early as February 1853 ships were loading pilings and spars at Coveland for transport to booming San Francisco.

There appears to be no documented evidence of commercial sawmills on Whidbey until decades later, but by 1852 a mill was operating at Port Ludlow, and in 1853 Pope & Talbot opened a steam-powered mill at Port Gamble. Rafts of logs from the island were towed over for milling. In 1858 Lawrence Grennan (d. 1869) and Thomas A. Cranney (1830-1907), who owned a general store in Coveland, built a mill at Utsalady on Camano Island, the first in the county. The difficulties of harvesting and moving timber with nothing but heavy hand tools and plodding oxen dictated that only trees less than two miles from shore could be profitably taken; interior forests remained largely undisturbed until steam-powered donkey engines and horse-drawn rail carts made them accessible.

Getting Around

Deer trails and ancient paths used by Native Americans were all that connected Whidbey's earliest white settlers. The first wagon roads, cut in the mid-1850s, were hardly better. When not reduced to quagmires they allowed some wagon travel between settlements, but for many years canoes were more convenient, often rented from the Skagits, with Skagit paddlers. A handful of semi-retired sea captains in Coupeville had sloops or other sailing craft, used mostly for commerce, including the export of timber.

On February 9, 1855, Isaac Ebey traveled from Port Townsend to Coupeville on a steamship misidentified as the Major Tompkins (which had blown up in 1851). Whatever its name, the Ebey ship and the sidewheeler Mary Woodruff were the first steamers to stop at Whidbey Island, and before long a variety of small, independent trading vessels, mostly steam-driven, would visit Oak Harbor, Coveland, and Coupeville carrying produce, tools, equipment, and a few luxuries such as cloth and tableware. The doughty craft also stopped by the island's smaller and more isolated settlements, announcing their arrival with a steam whistle. In a still cash-scarce economy, much of the trade was by barter.

Whidbey Islanders soon found themselves less alone on north Puget Sound. Port Townsend and Seattle saw their first American settlers in 1851. In 1854 the former, at the entry to Admiralty Inlet, became headquarters for the Puget Sound Customs Collection District, where all ships had to stop before proceeding south. In January 1861 the Red Bluff Lighthouse went into service atop a 90-foot cliff on Whidbey's west side to guide ships in. Later renamed the Admiralty Head Lighthouse, it stood until 1903, when the completion of Fort Casey as part of the defensive "Triangle of Fire" ("Triangle of Fire ...") forced its relocation.

Steamboats soon were key to the islanders' survival, or at least their prosperity, but it would be the 1890s before there were enough people to warrant scheduled boat service. When it did come, several ships of the legendary Mosquito Fleet were used over the years, including the sternwheeler Fairhaven (built in 1889) and the propeller-driven Camano (1906), Calista (1911), Atlanta (1913), and Whidby I (1919). In 1922 the Calista, sailing from Oak Harbor to Seattle, was rammed by the Hawaiian Maru while entering fog-shrouded Elliott Bay in Seattle. She sank within a half-hour, but the only loss of life was a coop of chickens.

With the arrival of more people, better equipment, and improved methods, the roads of Central Whidbey were gradually expanded and made more passable. Still, it was not until 1902 that a rough road was pushed through from Coupeville to South Whidbey. By then the automobile age was fast approaching, and Whidbey would be greatly affected. At least one source states that in 1912 "an auto ferry to Anacortes began, with a run to Camano Island added soon afterwards" (Washington State's Historic State Roads, 57), but does not say where on Whidbey the boat landed. By 1914 a small car-carrying ferry connected Whidbey to Fidalgo Island at Deception Pass, and served until the completion of the Deception Pass and Canoe Pass bridges in 1935. By 1915, mainland motorists could drive to Utsalady on Camano Island and board a four-car ferry that landed at Polnell, east of Oak Harbor. The Seattle Times reported that year that Whidbey and Camano had "above average country roads" ("Tour of Islands ...").

South Whidbey

For more than 30 years after Isaac Ebey's arrival, South Whidbey remained uninhabited by settlers save a few solitude-seeking pioneers living off the land. Logging would change this. Almost all timber was exported, and the east shore was most amenable to maritime commerce. The west shore was much less so. Admiralty Bay was exposed and had strong currents. Mutiny Bay, ominously named for reasons in dispute, had strong tide rips. The names of Useless Bay and Cultus Bay ("cultus" being Chinook trading jargon for "worthless") were accurately descriptive.

In 1883 (or 1875, depending on the source), brothers Edward and Henry Hinman filed a logging claim on the southeast shore overlooking Possession Sound. They named it Clinton, and it soon had a dock, a small hotel, and a post office -- "the first semblance of a town on South Whidbey Island" (Cherry, 1). By 1910 Clinton was a successful little community, and by 1919 car ferries ran between it and Mukilteo, as they still do (2022).

In 1890, about five miles north of Clinton, a young German immigrant named Jacob Anthes (1865-1939) partnered with Seattle investor James Weston Langley (1837-1915) to form the Langley Land and Improvement Company, which in November purchased a tract of land on Saratoga Passage. Five months later, the company filed a plat for 244 lots, and for obvious reasons named it Langley. First incorporated as a town in 1913, it is now the only incorporated city on South Whidbey. The two other incorporated municipalities are the city of Oak Harbor and the town of Coupeville.

Several other settlements, mostly on South Whidbey -- due to bad luck, bad location, choice, or other factors -- did not develop as the island's three incorporated places would. Among these are Austin, on Mutiny Bay; Glendale, about two and a half miles south of Clinton; Bayview (originally Newell), which overlooks Useless Bay; Bush Point on the west shore; Greenbank, at the entrance to Holmes Harbor in the east; Maxwelton, on the south shore of Useless Bay; and Saratoga, four miles northwest of Langley.

Unincorporated Freeland on Holmes Harbor is rather a special case. Founded in 1900 as a quasi-socialist utopian community, it survived the failure of that plan and has thrived. Its population was 2,252 in the 2020 census, more than Coupeville (1,964), almost double that of Langley (1,169), and second only to Oak Harbor and Naval Air Station Whidbey Island (24,622).

Ebey’s Landing National Historical Reserve

The National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978 recognized the outsize role played by Central Whidbey Island in the development of north Puget Sound. The law established Ebey's Landing National Historical Reserve, the first, and still only, historical reserve in the country. Centered on Coupeville and surrounding Penn Cove, the 17,572-acre reserve integrates the town, historic farms, Native and pioneer land-use traditions, and ecologically significant areas.

The reserve is managed collaboratively by a trust board comprising the National Park Service (NPR), Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, the town of Coupeville, and Island County, with input from other interested parties, including the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, NASWI, and property owners. Rather remarkably, approximately 85 percent of the land within the reserve is privately owned, with the rest a combination of local, state, and federal ownership. According to the NPR, the reserve attracts an estimated one million visitors each year.