On January 27, 1909, Samuel Cosgrove is sworn in as Washington's sixth governor. The new governor is seriously ill with Bright's disease, a kidney disorder that will ultimately prove fatal. When he arrives at the capitol the audience is shocked by his weakened appearance, and many break into tears. But as he delivers his inaugural address Cosgrove seems to gain strength; it is the pinnacle of a long-sought dream in his life. He will leave Olympia two days later and not return, dying in California after two months. Based on his brief inaugural speech, he will become known as "Washington's One-Day Governor," but the appellation fails to capture the real story of Samuel Cosgrove.

Chasing Down a Dream

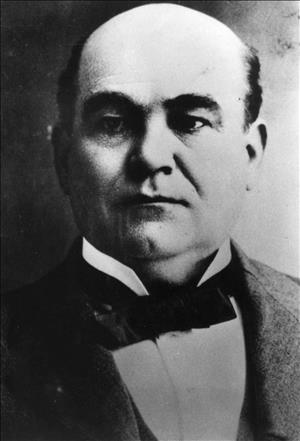

Samuel Cosgrove (1847-1909) would say in a rather flowery 1908 story in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that his ambition to become governor had begun 40 years earlier, when his father refused to support him in his ambition to go to college. (The story was written by Eugene Lorton [1869-1949], a political advisor to Cosgrove who also was editor of the Walla Walla Bulletin.) Born and raised in Ohio, Cosgrove eventually left the state and moved to Pomeroy (Garfield County) in 1882. An attorney, he practiced law in Pomeroy and served as mayor for five terms. He became active in Republican politics and served on the Washington State Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1889, which led to statehood for Washington the following November. By this time his dream to someday be governor of the state was becoming well-known to his peers, though his political base was so limited that few expected it to ever happen.

He became active in state politics. It was a good fit for Cosgrove, who was blessed with an exuberant personality and an ability to easily make friends from all walks of life. However, until 1907, candidates for state office were chosen by the political parties themselves, often at conventions, sometimes by petition. Though he was well-liked and respected by his fellow Republicans and worked in a variety of positions, when it came to the governor's chair, Cosgrove had to content himself to support the party's candidate for years.

His chance came in 1907, when the Washington State Legislature established a direct primary system for candidates for state office, allowing voters to choose candidates in a public primary. It was perfect for Cosgrove. He promptly launched a bid for governor in the upcoming election, and campaigned throughout much of the state for the next 18 months. His personality and perseverance paid off: He won the Republican nomination in Washington's first primary in September 1908, and he was handily elected governor on November 3 with more than 62 percent of the vote.

It was widely known during the campaign that Cosgrove was ill with what was then called Bright's disease, chronic kidney inflammation that could prove fatal. (In the twenty-first century, the illness is called glomerulonephritis.) He was too weak to campaign during the final weeks prior to the election – he was not even able to attend a Republican rally in Pomeroy a few days before voting day – and The Seattle Times published several articles the week before the general election about the precariousness of his health. Shortly after the election his condition deteriorated significantly, and on November 7, The Seattle Times reported that he was near death.

By the following week Cosgrove had regained enough strength to travel by train to Paso Robles, California, where he planned to recuperate with an assist from nearby mineral hot springs, which were believed to have health benefits. His condition fluctuated for the next two months. He initially seemed to recover, but in early December his condition became critical and he was again near death. Nevertheless, Cosgrove rallied once more. By the beginning of 1909, it was hoped that he would be able to return to Olympia for his scheduled inauguration on January 11. Winter weather in Washington forced him to delay the trip north, and reports circulated that he would not return until spring. Governor Albert Mead (1861-1913) remained in office during the interim.

In late January Cosgrove left California in his private railcar, "California," and after a somewhat arduous trip north, arrived in Olympia in the early afternoon of Wednesday, January 27, to sunny skies and a temperature in the 40s. The railcar was switched to a side track, and after a brief meeting with various dignitaries, he was taken by automobile – probably the first governor in the state to travel to his inauguration by car instead of carriage – to the capitol. (The car was loaned by suffragist May Hutton [1860-1915] of Spokane and sported a large banner across the back that read "Votes for Women." This probably was fine with Cosgrove, who favored women's suffrage.)

A Powerful Moment

The inauguration took place in the assembly room of the House of Representatives shortly after 3 p.m. in front of a packed house. Cosgrove walked down the aisle to the podium, assisted by senators Alex Polson and John Stevenson. The two men helped him out of his overcoat as he briefly took a seat, and the crowd was shocked when they got a closer look at him. His weight had dropped from 195 pounds to little more than 110 pounds; he was shrunken and emaciated, and as described by the Seattle Star, "seemed ready to collapse with every word he spoke" ("As Dillon Saw ..."). Women in the audience began audibly crying, and shocked exclamations slipped out from some of the legislators as well as other men in the audience.

Though a brief, minute-long speech had been prepared for Cosgrove, he didn't read it. He instead gave his own 10-minute address, starting out in a weak voice but seeming to gather strength as he went. He thanked the crowd for its support and admitted that he had nearly died: "A few weeks ago I was led down into the valley of the shadow of death and I was allowed to peep almost on to the other side, but for some reason or other I have been called back and I am here with you again" ("Gov. Cosgrove's Life ..."). He asked that the legislature pass a local option law, which would allow voters in any town to vote whether to license saloons in their community. (It did.) He asked for a constitutional amendment to give the state railroad commission additional power to control rates, and he asked that the new direct primary law be strengthened. He asked for a joint resolution granting him a leave of absence pending his recuperation, and then took the oath of office from Washington Supreme Court Justice Frank Rudkin (1864-1931).

It was a powerfully emotional moment. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, as was its wont in its coverage of Cosgrove, was upbeat: "Although thin and frail ... Gov(ernor) Cosgrove reached the supreme moment of his career with splendid courage ... When he began his speech, there was an exalted look in his eyes, as if he realized fully that he was about to see the fulfillment of his life's ambition" ("Gov. Cosgrove's Life ..."). The Seattle Times was more blunt, describing the scene this way: "Never was there, and it is doubtful if there ever will be, a more pathetic official ceremony to the living than that enacted yesterday afternoon" ("Sympathy Shown ..."). The Seattle Star penned its own dramatic version. Its reporter began one article by describing the governor "like a father giving his last words to his children" ("As Dillion Saw ...").

Cosgrove remained in Olympia for two days after his inauguration and conducted state business, including making several appointments, from his private railcar. He also met with Lieutenant Governor Marion Hay (1865-1933) to discuss further appointments that he wanted Hay to make after he returned to California, since Hay would be acting governor in Cosgrove's absence. The new governor had such a good time that his son Howard and others guarding the railcar relaxed their watch to some extent and allowed many of his old friends to drop in and visit.

Cosgrove spent the rest of the winter in California, and the news from Paso Robles was hopeful as spring began. It was said that he might be sufficiently recovered to return to Olympia by late spring or early summer. But it was not to be, and he died from a massive heart attack in the early morning hours of Sunday, March 28. He has since become known as "Washington's One- Day Governor," based on his inaugural address in Olympia. The nickname is flawed but it has stuck, overshadowing the story of his life and resolve to reach his dream.