Albert Mead served as Washington's fifth governor from 1905 to 1909. A Republican, he was known as an affable straight arrow who took a keen interest in a wide range of issues facing the state, from the significant to the slight. He proved to be an effective executive who encouraged some of the progressive seeds which began to bloom in the state during his administration.

Beginnings

Albert Edward Mead was born December 14, 1861, in Manhattan, Kansas, the son of William Mead (1833-1911) and Harriet Carleton Mead (1828-1867). He had an older sister, Frances (1857-1942), and a half-brother, Harry. He moved to Iowa at age 13 and to Anna, Illinois, two years later. He attended college at Southern Illinois Normal College (later Southern Illinois University) and went to law school at Union College of Law (now Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law) in Chicago, graduating in 1884. He was admitted to the Illinois Bar in 1885 and moved to Wichita, Kansas, soon after, where he practiced law for four years. In 1887 he married Elizabeth "Lizzie" Brown (1864-1898), and four children followed: May, Wendell (1891-1952), Rollin, and William "Damon" (1896-1976).

Mead moved to Washington Territory in 1889, months before it became a state. He lived briefly in Bellingham before settling in Blaine, where he practiced law for the next nine years. He was elected mayor of Blaine in 1892 and served one term. It also was in 1892 that he was elected to the legislature, where he similarly served one term. His obituary in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer says that it was "here his ability in public affairs first became generally known to the people of the state" ("Albert E. Mead ..."). He served as chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, and he took an active role in the legislative process of choosing a U.S. senator (U.S. senators were chosen by state legislatures before 1913, when the 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution established direct elections).

Mead was elected prosecuting attorney of Whatcom County in 1898 and moved to Bellingham. That same year, his wife Lizzie died. In 1899 he married Mina Piper (1860-1941) and they had a son, Albert V. (1900-1955). Mead was reelected to a second term as prosecuting attorney in 1899, and by 1904 he was under consideration for a nomination for judge on the Whatcom County Superior Court. Instead, he became a dark-horse candidate for governor. Until 1907 the state's gubernatorial candidates were typically chosen at party conventions, or sometimes by petition, and many had expected that the sitting governor, Henry McBride (1856-1937), would be nominated at the Republican convention that year. However, McBride had incurred the animosity of the powerful railroad lobby, which succeeded in blocking his nomination.

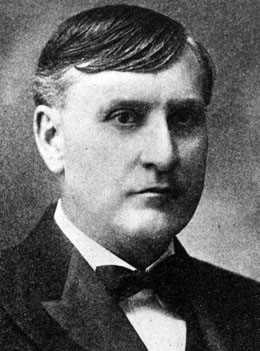

There were other, better-known candidates, but the convention delegates from Whatcom County successfully pushed to make Mead the nominee. The announcement came so quickly and was such a surprise that there was talk among his detractors that "the railroads had nominated Mead" ("Albert E. Mead ..."), but this was not true. Mead was a solid, known candidate with nearly 20 years of legal experience and few, if any, blemishes on his record. A large, friendly man with a shock of dark hair that spilled down his forehead, he was viewed by his contemporaries as straightforward, even-tempered, and honest. He was elected in November 1904 with more than 51 percent of the vote, defeating Democratic candidate George Turner (1850-1932) by a more than 10-percent margin.

A Hands-On Executive

Mead was sworn in as the state's fifth governor by Chief Justice Wallace Mount (1859-1921) of the Washington Supreme Court on January 11, 1905, in a simple, almost austere ceremony in the House of Representatives – there wasn't even a band, which was standard for any kind of ceremony in those days, big or small. He delivered a detailed inaugural address with a number of recommendations, which included a state railroad commission to regulate rates and deal with abuses. He also proposed a state tax commission. Prior governors had argued for both, though none had been successful. This changed in 1905, when the legislature passed bills that established both commissions. Mead additionally argued for "road legislation," which was similarly approved. In March he signed a bill creating the office of Highway Commissioner, which was designed to work with county commissioners to build state roads. (This was particularly timely. In early 1905 the automobile was considered a novelty and there was still talk of building "wagon roads," but this would soon change.)

He touched on a total of 22 topics in his address, and ended it with a frontal attack on lobbyists, which surprised everyone:

"These enemies of civic righteousness and good government, bearing no commission from the people, no letters of marque to engage in political privateering, acting under no oath of office, worshiping only the god Mammon, cherishing no high ideals, will haunt the corridors of this capitol building from now until adjournment. They dare not fight in the open for they realize that, like the fatal basilisk 'whose breath was poison and whose look was death,' their active, open espousal of any cause would damn it" ("Governor Mead's Message").

Mead soon received his first real challenge as governor, and it was generated by none other than a powerful lobbyist in the state, George Stevenson. Stevenson had been retained by Charles Sweeny, a wealthy politician from Spokane, to woo legislators into voting him into the U.S. Senate, but the effort failed. This infuriated Stevenson, who retaliated by inducing various parties to coax the legislature into introducing a bill to move the state capital to Tacoma. There had been efforts to move the capital from Olympia before. This included a proposal to move it to Tacoma just four years earlier, but it had not passed the legislature. The 1905 effort was more successful: The Senate quickly passed the bill, while the House did two weeks later. The bill then went to Mead for his signature.

Mead sat on it for a week before issuing a stern veto on February 27. He pointed out that the state constitution required an amendment to change the seat of government, and the amendment had to be approved by two-thirds of state voters. (Had he signed the bill, the removal question would have appeared on the ballot in the November 1906 general election as a proposed constitutional amendment.) He argued accordingly that both houses of the legislature also had to pass the proposition by an identical majority before submitting it to the voters. Though the Senate passed the bill with the requisite majority, it did not receive two-thirds of the vote in the House. The governor took it further:

"From the inception of the consideration of this measure, evidence has been constantly accumulating that this bill was forced through the legislature by a practice bordering close to the line of intimidation and coercion… The people are at all times entitled to express their candid, voluntary and honest judgment upon public questions and in the selection of public servants. I ask that the legislature be afforded at all times the same privilege and prerogative" ("Governor Vetoes ...").

His veto was promptly sustained by the Senate, and even The Seattle Times – which tended to be liberal in its criticism of Mead – approved, acknowledging in an editorial that the governor "did himself credit and the State honor when in a clean-cut and logical message he vetoed the crazy proposition ..." ("The Governor's Veto"). A resolution (which did not need Mead's signature) to place the removal question on the 1906 ballot was deferred by the Senate four days later.

By the middle of his term in 1907, Mead had become known as a detail-conscious governor of many aspects of his administration, from large to small. He also was a prolific writer. There was considerable anticipation of what he would cover in his 1907 message to the legislature, and the governor did not disappoint. He discussed an array of topics, ranging from a call to create a department of archives to care for the state's earliest records, as well as a request for the completion of all the portraits of former governors of Washington state and territory, to recommendations to create a state board of finance and to establish a modern state reformatory to replace a smaller one then in existence. (The legislature passed a bill that year to create the reformatory, which opened in Monroe in 1910.)

A Nod to the Progressives

Mead also favored other legislation that reflected the slowly increasing shoots of progressivism sprouting in the state. He supported a direct primary law, which would provide for candidates for state office to be chosen in a public primary. Though a similar bill had failed in the 1905 legislature, it passed in 1907, leading the way to the primary system that Washingtonians know today. He also called for the creation of congressional districts in the state, and the legislature subsequently passed a bill creating three districts. Other progressive bills were not successful in 1907; for example, a bill providing for the initiative and referendum failed in the legislature that year. (A similar bill, which also allowed voters to recall state elected officials, passed in 1911 and was approved by Washington voters in 1912.)

Mead faced an unexpected challenge later in the year when the financial Panic of 1907 struck in the autumn. What had started as a recession suddenly accelerated in October into a sharp but mercifully brief financial crisis in the United States, with runs on banks by panicked depositors that threatened to spiral further out of control. A larger downturn was avoided when wealthy American financier J. P. Morgan (1837-1913) and other powerful financial titans stepped in and provided financing to save some struggling banks, while Morgan took over others.

Though the crisis wasn't as severe in Washington, Mead declared a legal holiday for the final two days of October, giving the state's banks the option of closing. It was not a popular decision. A few of the leading bankers in the state told Mead they did not believe the holiday was necessary. Some cities, such as Everett and Port Townsend, ignored it. The governor explained that he had taken the action out of concern that smaller local banks in the rural areas of the state would be unable to obtain sufficient cash during the panic. However, the crisis passed quickly. It was necessary for some banks to issue clearing house certificates (scrip) for a time, but by the end of November the worst was over, though the economic aftereffects lingered into 1908.

A Gracious Defeat

Mead ran for reelection in 1908, but pursuant to the new direct primary law, candidates for the governor's seat were now chosen by the people, not the candidate's party. Thirteen men – eight of them Republicans – ran for the position in Washington's first primary on September 8, 1908. Mead came in second, losing by a nearly 4-percent margin to Samuel Cosgrove (1847-1909), a Pomeroy lawyer who used his prodigious ability to connect with voters to offset his lack of experience in statewide office. Mead was gracious in defeat, and said he was glad it that it was Cosgrove who had been nominated instead of some of the other candidates. The Seattle Times couldn't resist a dig at that, wryly exclaiming in an editorial, "The announcement that Gov. Albert E. Mead is glad that Judge Samuel G. Cosgrove was nominated has cleared away the gloom like the passing of a hat disperses a crowd" (editorial, September 13, 1908, p. 6).

There does not seem to have been a particular reason for his loss. He was criticized for granting several hundred paroles during his term, including to men convicted of serious crimes, and this probably cost him votes. His declaration of a legal holiday during the Panic of 1907 may have cost him a few more. His detractors viewed him as too friendly and eager to appear to please, a fact acknowledged by the Mead-friendly Seattle Post-Intelligencer, but there were no allegations of wrongdoing made against Mead; he was just a nice guy. Part of the problem seems to have been the large number of candidates on the ballot, which had the effect of dispersing the votes between them and preventing a clear majority for any one candidate. For example, Cosgrove won the primary with a mere 25 percent plurality, while Mead collected 21 percent and the third-place finisher, former governor Henry McBride, gathered more than 20 percent of the total vote. The remaining candidates each won a percentage in the single digits.

Cosgrove won the general election in November, but by then he was gravely ill with kidney disease. It was not clear when, or even if, he would be sworn in. Shortly after the election, he traveled to California in an attempt to recuperate. The state constitution prohibited him from becoming governor if he was out of state, even if temporarily, and Mead remained governor in the interim. Cosgrove met with Mead before his departure and suggested he carry on as governor, but the new governor's inauguration was ultimately delayed by only slightly more than two weeks, until January 27, 1909.

Afterward

Mead gave his final address to the new legislature two weeks prior to Cosgrove's inauguration. He urged that a new state mental hospital be created, and he called for a state tuberculosis sanitarium. He argued that race-track gambling should be banned, and the requisite bill passed the legislature that year. (Legal horse racing returned to the state in 1933.) He also argued in favor of a local option law, which would allow voters in any town to vote whether to license saloons in their community. This was an especially contentious issue, and similar bills had failed in the 1905 and 1907 legislative sessions. It passed in 1909, but not without a great deal of rancor and bitterness.

He also asked that the direct primary law be amended. "Efforts were made by some of the candidates in the late primary election to defeat the purpose of the law and violate its spirit by filing declarations of candidacy solely for the purpose of aiding or defeating other candidates for the same office," he explained. "Such an abuse of the law should not be tolerated" ("Reduce Size ..."). This was a remarkable statement coming from the governor, who was not known for hyperbolic allegations. The suggestion was not followed.

Mead returned to Bellingham and resumed practicing law. In December 1911 he was elected president of the Bellingham Chamber of Commerce and was unanimously reelected the following December. He chaired a committee to raise funds for the local YMCA, and he was a frequent speaker on a multitude of topics. In the winter of 1913 he came down with a particularly serious case of influenza, which proved difficult for him to shake. His doctors discovered that he had a damaged heart valve, and his illness had exacerbated the condition. They urged caution, but Mead refused to take them seriously and instead resumed working on a reduced schedule. This was a mistake, and he died from a ruptured aortic arch at his home at 2311 J Street on the afternoon of March 19, 1913.