For more than 50 years, the Puget Sound Navigation Company (PSN) carried goods and passengers between towns in Washington and British Columbia. PSN was founded by Walter Oakes, Charles Enoch Peabody, and several associates, and incorporated in 1900. Six years earlier the men had started Alaska Steamship, a company that boomed during the Gold Rush era transporting miners and supplies to Alaska and the Yukon. Through mergers and competitor buyouts, PSN came to dominate passenger service on Puget Sound. Also known as the Black Ball Line, it helped pioneer auto-ferry service, a vital part of Washington’s transportation system. Leadership was transferred to Peabody’s son Alexander in 1928. In the 1940s, after strikes, fare increases, and scheduling snafus stranded tens of thousands of riders, civic groups and businesses petitioned state officials to create a state-run ferry system, and on December 30, 1949, the state agreed to buy most of PSN's ships, docks, and routes. Washington State Ferries became operational on June 1, 1951.

Oakes and Peabody, Steamship Company Founders

Before steamships arrived, sailing vessels and canoes were the main methods of transportation on Puget Sound. The ships carried "log piles, square timber, and sawed lumber away from the heavily forested shores of the Sound bound for San Francisco, the Sandwich islands (Hawaii), and even Australia and China. They returned such goods as sugar, salt, syrup, rice, dry goods, paints, liquor, tobacco, nails, and window glass ... The idea of introducing American steamships onto the waters of Puget Sound generated excitement for local boosters who wanted to develop the commercial interests of the region, attract settlers, and gain bragging rights over Portland, Oregon – the main settlement on the Columbia River" (Puget Sound Ferries, 27).

The parent company of Puget Sound Navigation was Alaska Steamship, founded in 1894 by Walter Oakes (1864-1911), Charles Enoch Peabody (1857-1926), and four others. Oakes and Peabody came from families steeped in the shipping and transportation industries. Oakes, born in St. Louis, Missouri, was the son of Thomas F. Oakes (1843-1919), long-time president of the Northern Pacific Railroad Company. A graduate of Phillips Andover Academy and Harvard University, Oakes moved to Tacoma after graduation and got involved in Alaska-bound steamboat traffic.

Peabody was born into a wealthy and well-known family in Brooklyn, New York. His grandfather, Alexander C. Marshall (1799-1859), was part of the family that in 1818 co-founded the Black Ball Line, a venerable company whose sailing vessels handled both passenger and freight traffic between New York and Liverpool, England. Peabody’s own maritime career took a roundabout route. He worked first on Wall Street and then tried his hand at farming in Minnesota. In 1882, he was appointed a special agent for the U. S. Treasury Department, managing the U.S. Revenue Cutter service on Puget Sound. He resigned that post to move to Port Townsend, where he worked in a bank before co-founding the Alaska Steamship Company. Its first vessel was the Willapa, which carried 79 passengers and 23 horses to Juneau, Alaska, on March 3, 1895.

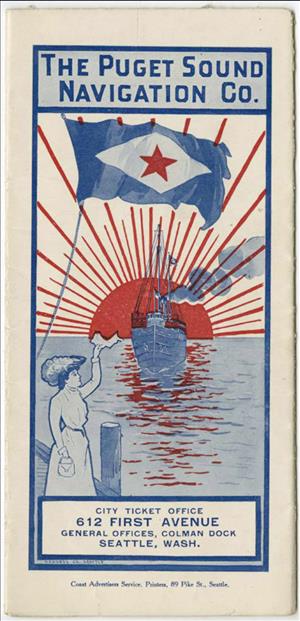

Alaska Steamship got an economic boost in 1897 when gold prospectors, desperate to make their way to the Klondike, booked passage on the new steamer service. Leaving Seattle every two weeks, Alaska Steamship transported not only a steady stream of miners but also carried food and equipment, from hogs and cattle to sleds and wagons. In a nod to Peabody’s lineage, the ships sailed under a flag reminiscent of the Black Ball Line but with one difference: The black ball on a red background added the letter 'A' (for Alaska) in the center.

As the business grew, Alaska Steamship required larger ships. The smaller vessels were used to create a new company called Puget Sound Navigation. Peabody and Oakes incorporated the business in September 1900, listing its assets as $50,000. Over the next decade, PSN bought out most of the competition. In 1902, it purchased the Thompson Steamboat Company for $150,000 in cash, and the next year merged with the La Conner Trading and Transportation Co., which had been founded in 1889 by Joshua Green (1869-1975).

A native of Jackson, Mississippi, Green traveled with his family to Tacoma in 1886 and later took a job on the sternwheeler Henry Bailey, part of the famed Mosquito Fleet on Puget Sound. Green saw his future in shipping and took out a $5,000 loan from Seattle financier Jacob Furth to purchase his first sternwheeler. More vessels were added, and by 1900, the La Conner Trading and Transportation Co. was an industry contender. After the two companies merged in 1903, Green became president of PSN while Peabody moved up to become chairman of the board. Green resigned his post in 1927 to pursue a career in banking but never forgot his roots. In 1974, at his 105th birthday party, his cake was decorated with a drawing of a sternwheeler and the phrase: "Still on deck at 105." He died the following year.

The Mosquito Fleet was a primary means of transport on the Sound from the 1880s through the 1920s. "Often jerry-rigged, usually reliable, occasionally less seaworthy than they should be, and always more functional than fashionable, the ships steamed across the waterway transporting people and goods. By sailing nearly anywhere there was water, the Mosquito Fleet was essential to the growth of Puget Sound by allowing people to live anywhere along its 1,332-mile shoreline and still stay connected to the world around them" ("Mosquito Fleet").

Puget Sound’s Black Ball Line

In 1904, Alaska Steamship, Puget Sound Navigation, and allied businesses employed more than 600 men, and their trickle-down impact on Seattle’s economy was huge: "The companies have paid out in labor, supplies and boat building about $1,000,000 in the past twelve months. All supplies are purchased in Seattle and the figures at the company’s offices show that local merchants have received more than $7,000,000 in the past year. Then, the stockholders of the company are all Seattle men and reside here with their families. At the present time, the company is building a new vessel for the Alaska run which will cost in the neighborhood of $250,000. All material for the new boat, including the machinery, is furnished by Seattle retail and wholesale dealers. There is scarcely a firm in Seattle which is not benefited by this arrangement and each month many hundreds of dollars are distributed for provisions" ("American Boats Aid Seattle").

While Alaska Steamship ferried many of the Klondike gold-seekers north, Puget Sound Navigation focused on Puget Sound from its base at Colman Dock on the Seattle waterfront. "The waters of the Sound are continually dotted with the boats of this fleet, and it is not surprising that this traffic alone aggregates nearly six millions of dollars annually, and it is constantly on the increase" ("Fine Shipping Facilities"). With such high revenue at stake, there was fierce competition among steamship companies. One competitor was the Kitsap County Transportation Company, popularly called the White Collar Line. PSN had bigger ships, but Kitsap County Transportation had faster ones. Their bitter rivalry would go on for 20 years.

Disasters and Upgrades

Accidents, from collisions to running aground, occurred regularly on the shipping lanes. On January 8, 1904, the steamship Clallam, owned by Puget Sound Navigation, encountered gale-force winds and heavy seas and sank in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Three lifeboats were deployed, but various mishaps caused the small boats to either capsize or wreck, sending occupants into the frigid waters. At least 55 men, women, and children were lost. After a nine-day investigation, the blame was placed on the chief engineer who, it was said, had allowed the pump rooms to fill up with water, rendering the ship helpless. The jurors determined that the steamer was operating with a defective rudder and ill-equipped lifeboats.

Despite the disaster, PSN continued to grow. In 1905, the company commissioned at least 10 new vessels and replaced its fleet with steel steamers, many burning oil rather than coal. Two fast steamships were earmarked for the Seattle-San Francisco run, while new vessels were promised for Seattle-Tacoma and Seattle-Vashon Island. Vacationers seeking a comfortable way to access summer waterfront properties clamored for newer and faster ships, as well. In 1906, three steel passenger steamers were added to the fleet at a cost of about $200,000 each.

"With the advent of more roads, and a demand for vessels that could haul automobiles, Charles Peabody decided in 1919 to convert his trim-lined fleet to snub-nosed ferryboats" ("'Cap' Peabody, Man of the Sea ..."). Transporting automobiles was no easy feat in the early years. The cars had to be partially disassembled to get them on board, since the ships had not been designed for that use. Once they arrived at their destination, the cars had to be reassembled on the dock. The first steamer adapted by PSN to carry vehicles was the Whatcom, built in 1901. "The process used to transform the passenger vessel Whatcom into an auto ferry became standard procedure between 1912 and the early 1920s. The first auto ferries were all conversions. Changing the ... vessels involved removing the superstructure above the deck and widening the hull as well as widening the bow and stern to fit the landing slips and to provide the ramp necessary for the movement of cars on and off the ferry" (Puget Sound Ferries, 62). A superstructure was added atop the deck, containing a passenger cabin and wheelhouse.

The Next Generation

When Charles Peabody died in 1926, his son, Capt. Alexander Marshall Peabody (1895-1980), joined the company, and in 1929 he became president and general manager. At the time, PSN ran 17 routes with 25 vessels. Alexander Peabody reinstated the iconic Black Ball flag, which had been replaced earlier when the company was managed by Joshua Green. With this move, PSN became synonymous with Black Ball Ferries. "Alexander Peabody shared his father’s business acumen and competitive zeal, and soon grew the company to become the dominant water transportation provider throughout Puget Sound. One strategy to keep up with the changing times was to take older passenger ships – either that were already in the fleet or those purchased from retiring fleets – and retrofit them to carry automobiles. Among the most famous of these conversions was the Kalakala ("Black Ball: 200 Years Strong").

During the Great Depression, unions representing ferry workers were pressed into service to negotiate higher wages and better working conditions. At first, Peabody simply ignored the unions, refusing to recognize them until 1933. In 1935, a 33-day strike stopped all ferry traffic on Puget Sound. Black Ball was able to ride it out, but its chief rival, Kitsap County Transportation Company, could not. Peabody acquired his competitor by assuming $140,000 in liabilities. After the 1935 strike, Peabody continued to buy out smaller companies. As PSN took over new routes, the increase in service meant the fleet needed to expand. In 1937, Peabody bought six wooden-hulled vessels from California ferry systems and purchased nine more in the early 1940s. In 1942, Black Ball had 23 ships that could carry 22,500 cars and 315,000 passengers daily. "Fifteen different routes and 452 sailings each day is evidence of the Herculean task. In cooperating with the needs of the U. S. Government to provide war workers, Peabody also agreed to reduce ferry fares by 10 percent" (Puget Sound Ferries, 84).

Controversial Fare Increase

Although Peabody kept fares low during World War II, he sought to make up for lost revenue after the war. A 10-percent fare increase was approved reluctantly, but a request for a 30-percent rate hike in 1947 was met with resistance. After much debate, state officials awarded Peabody a 10-percent increase but deemed he had to refund two-thirds of each fare retroactive to January 1. Peabody threatened to shut down the ferry system completely.

This controversy came just months after 70 Black Ball engineers went on strike for six days in March 1947, seeking higher wages and a reduced work week of 40 hours versus 48 hours. When the engineers walked off the job, they crippled the entire fleet; 10,000 Puget Sound commuters were stranded. Buses and small aircraft companies tried to fill the void, and some residents banded together to charter their own ships. Governor Mon C. Wallgren (1891-1961) stepped in to arbitrate, hashing out an agreement that included a 10-percent wage increase, but kept the 48-hour work week. The contract was approved by a vote of 43 to 21.

Peabody’s iron grip on the ferry system continued. In 1948, a second strike was called, but rather than negotiating with workers, Peabody halted ferry operations, hoping that public pressure would convince the state to approve a fare increase. "Citizens and state agencies scrambled again, and were once more outraged at the effects of having one person in control of a vital link in statewide transportation. Seeking recourse, the state stepped in" ("Striking Ferry Engineers Shut Down ...").

Washington Begins Ferry Service

Although Gov. Wallgren supported a state-run ferry system, he lost the 1948 gubernatorial election to Arthur Langlie before he could take action. "For the next year, Peabody and Langlie went back and forth on the issue of public and private. Peabody remained adamant about retaining control of his ferries. Langlie retorted that he and the public had lost confidence in Peabody’s operation" ("Turning Point 9 ..."). Finally, on December 30, 1949, the state announced that it would buy most of PSN’s equipment and operations and assume control of the ferry system. The purchase included 16 ships at a cost of $5 million. "While the captain [Peabody] remained convinced that state-owned ferries were an unholy monopoly, by 1951 he was prodded by his bankers to sell his Black Ball Line to Washington’s Toll Bridge Authority. Most, including Capt. Peabody, thought that Puget Sound’s ferries would eventually be replaced by a network of bridges and tunnels" ("State Ferries Strife is Nothing New").

On June 1, 1951, Washington State Ferries began service. Passengers noticed little difference. Routes and schedules remained the same. Many ferry workers simply left the Black Ball Line one day and joined the state ferry system the next. Even the phone number was unchanged.

When it took over ferry service, the state "inherited an eclectic fleet that included converted passenger steamers, vessels made completely of wood, and a streamlined silver ferry that looked like it was out of a Buck Rogers movie serial. The newest vessel was 16 years old, and much of the fleet had been designed for the slim cars of the 1920s and 1930s ... Many vessels of the Black Ball Line survived well into the 1970s" (Ferries of Puget Sound, 9).

Although most of the ships and routes were sold to the state, Peabody moved his remaining fleet to British Columbia and retained the right to the Victoria-Port Angeles route, sailing under Black Ball Ferries, Ltd. He later sold the single route to Robert Acheson, a former employee of Puget Sound Navigation. When Acheson died in 1963, his wife Lois took over until her death in 2004. Her estate was left in trust to the Oregon State University Foundation to endow its college of veterinary medicine. In 2008, the company changed its name to Black Ball Ferry Line. It continues to sail the M. V. Coho, built in 1959, on its route between Victoria and Port Angeles.