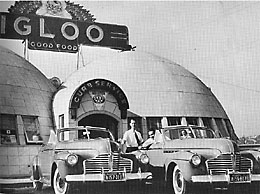

In this People's History, Irene (Borlaug) Wilson recounts her memories of the Igloo Restaurant and World War II in Seattle. HistoryLink's Heather MacIntosh interviewed her in Seattle in May 1999.

On Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, Irene Borlaug walked from the apartment she shared with her sister at 6th Avenue and Seneca Street to the Igloo Restaurant. It was Irene's first job in Seattle. She'd recently moved from Williston, North Dakota, away from a somewhat contentious relationship with her father's new wife.

A Job To Love

Irene moved to Seattle with her sister to be closer to a boy she'd met. Once she moved to the Pacific Northwest, she decided she wasn't all that interested in the relationship. She was much more intent on getting a job, "I was desparate ... I really wanted to work!" It wasn't so much for the money. "The Igloo was a glamorous kind of job ... Compared to North Dakota, I guess anything'd be pretty glamorous. But don't get me wrong, the Igloo was great. I loved my job."

The short walk to the Igloo was generally pleasant, with one exception: "Two guys stood in a doorway and threw breadcrumbs at me when I'd walk by." Irene was 19, petite, and attractive. Irene got the job soon after she arrived in Seattle on a $30 train ticket. The walk might have been rainy at times, but Seattle was a welcome change from Williston. When she arrived in February 1941, "everything was green. Flowers were everywhere. I couldn't believe it." The rain was getting to her, though. "The first winter was the worst."

Thankfully, The Igloo, standing at 6th Avenue and Denny Way, wasn't that far from her place. It wasn't that far from Aurora Avenue either: The neon eskimo hovering over the two metal domes of the drive-in invited passengers from a distance. Irene's uniform, which included a short red skirt, red panties, white short-heeled boots, and white jacket, probably attracted more customers. She changed into her outfit once she arrived at the restaurant.

One fateful Sunday, shortly before noon, Ernie Hughes' father walked through the Igloo's doors, solemnly carrying a folded newspaper. Ernie Hughes owned the restaurant.

War

It was a moment Irene recalls vividly almost 50 years later. "He had the paper folded over, you know, so that you could just make out the headlines. He held the paper up so that everyone in the restaurant could see. The headline was just three letters -- WAR. The whole place was dead silent. Like we couldn't hardly move. Then over the [counter jukeboxes] they made the announcement 'all men report...' and the men just got up at once. The women, we were left there, dumb on our seats with blank faces. Nobody paid for anything, they just got up. They didn't even wait for their orders. Men just left the line. I couldn't believe it. I thought that was the end. That we were all going to die."

One of the waitresses, whose brother had been on a ship in Pearl Harbor, whispered to Ralph "I'm not waiting on any Japanese." She wouldn't have much opportunity -- Seattle's Japanese American residents were soon ordered to internment camps in Idaho and Wyoming.

Irene walked home, incredulous. Everyone in Seattle seemed affected. The two breadcrumb throwers stood stunned and motionless as she passed.

She soon decided to leave the Igloo, and Seattle, for California, where she briefly worked at an aircraft manufacturing plant, drilling tubes into metal parts. She wasn't very good at it. She realized this within a week, submitted her notice, and returned to Seattle, and her beloved job at the Igloo.

During the early 1940s, the place was hopping. "I liked working outside better. More freedom. Outside, you only had to worry about your tray. Inside, they had to bus the tables." Indoor waitresses wore white uniforms with blue-dotted aprons.

Irene enjoyed the atmosphere, and liked her boss Ralph Grossman, the other waitresses, and one of the two cooks. She and the other waitresses took their breaks at the lunch counter. One of the cooks frequently encouraged her to eat plates of pancakes, eggs, and bacon. "I was real little, and he was worried about my weight." He looked out for her. "He'd make sure I got home alright on late nights. I look back on that now, and I'm really glad. You know, it was just me and my sister here in a new city. It was good to have someone look out for me."

The Igloo was like a family. Part of this had to do with the management -- Ralph Grossman, who would later sell cars on Aurora. Ralph would send Irene across the street to the Dog House (another Seattle restaurant) to compare prices. Ralph was a decent business man, and a good person -- part of the reason Irene enjoyed working with him. He would sit in the restaurant, wearing a button reading "Uncle Ralph." He was friendly to all the customers. It was Ralph's idea to scour the hotels for attractive elevator operators for his new Igloo restaurant, a business venture he pursued with Ernie and Dorie Hughes.

Talking Norwegian

Ralph allowed the waitresses to take breaks at the lunch counter, Irene recalls proudly. "Nowadays you never see that. Waitresses in uniform eat in the back." Sometimes she'd sit there speaking Norwegian with Dorie Hughes. This aggravated Ernie -- he had no idea what they were talking about. "So we'd just laugh, and talk some more."

She stopped waitressing in 1942 when she married one of her best customers, Phillip Wilson. The Igloo operated for another decade. When she heard it had been torn down, she was quite upset. "It was a great little place. It would have made a great record shop or something." The Igloo still stands in Irene's mind as one of her best early memories of Seattle.