On April 10, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appoints former Tacoma Mayor and U.S. Senator Harry Cain to a seat on the federal Subversive Activities Control Board, a Cold War-era committee charged with ferreting out communists and other alleged enemies. Cain's tenure on the committee will be brief and turbulent, and come to be known as the "Cain Mutiny."

McCarthy's Friend, and then Foe

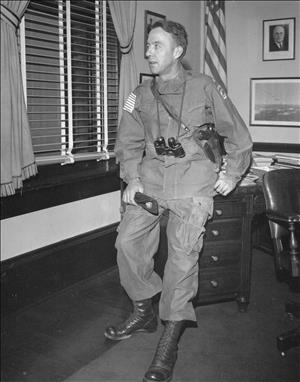

Defeated by Henry M. Jackson in November 1952 in his bid for re-election, former Tacoma mayor, war hero, and one-term U.S. Senator Harry P. Cain (1906-1979) returned to Tacoma to consider his future. There were rumors about a TV network news commentating job or a position in the newly elected Eisenhower Administration. "I’ve been mulling over a lot of things in the last two months and now I have to make up my mind," Cain told the Washington correspondent for the Tacoma News Tribune (Shannon).

Former friend and political ally Senator Joseph McCarthy (1908-1957) lobbied the new Secretary of Defense, Charles E. Wilson, to consider Cain as a candidate for Secretary of the Air Force or Assistant Secretary of the Army. Although Cain had publicly supported Eisenhower for the Republican nomination, and had served with distinction in the military government branch of Eisenhower's staff in London during the war, Cain’s controversial Senate record may have led to questions about his suitability for high appointive office. However, on April 7, 10 weeks after Eisenhower assumed office, the White House announced that Cain would have his choice of three jobs: a seat on the Subversive Activities Control Board (SACB), a seat on the Civil Service Commission, or a top job in the Veterans Administration. On April 10, Cain was nominated to fill a vacant seat on the SACB, with the promise that he would be re-appointed at the next opportunity.

During his confirmation hearings, Cain was sharply questioned by his former Democratic colleagues about controversial positions he had taken while a member of the senate, but was confirmed by the Senate on April 28.

It is unclear how much vetting Cain received before his nomination. Had they explored his background in more detail, they would have discovered a pattern of defending controversial groups and individuals he felt had been unfairly accused. Those included Japanese Americans in the months following Pearl Harbor, two Cleveland mobsters who Cain believed had their civil rights violated by the Kefauver Committee, the liberal Anna Rosenberg during her nomination as Assistant Secretary of Defense, and then Senator McCarthy himself when columnist Drew Pearson attacked his war record.

The SACB was an independent, quasi-judicial entity created by Congress to determine – based on formal testimony presented before the board by the Justice Department and the accused organization – whether the organization in question should be forced to register as a Communist-action or Communist-front organization. Rulings of the SACB could be appealed all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The public’s fear of communism provided the Republicans with a potent campaign issue in the 1952 national election. The Republican Party Platform charged the Democrats with "shielding traitors" and "undermining the very foundations of our Republic" (Smith). Realizing that he was going to have to face the issue of McCarthy and communism in the coming campaign, Eisenhower fought hard to have Richard M. Nixon chosen as his running mate and include conservatives like Cain in his administration. A new Executive Order 10450 broadened the criteria used for investigating new and existing federal employees. By adding "security" to "loyalty," the new criteria greatly expanded an employee’s grounds for dismissal.

Before long, Cain was receiving calls from individuals who were being investigated by the government. The cases set off multiple alarms in his mind. In some cases, he believed that the employee’s basic constitutional guarantees were being ignored. The manner in which many of the cases were being handled smacked of intrusive big government at its worst and of poorly trained, ill-informed bureaucrats trying to implement the governments none-too-clear policies. To make matters worse, the lives of the employees and their families were being adversely impacted, sometimes severely so, by unproven allegations and smear tactics, making it hard for them to get another job, or even to live in their own communities. If something wasn’t done, this could become a public embarrassment to the President. Once again, as he had in the Senate, Cain decided to listen to his conscience and do what seemed right to him at the time.

Cain began to express his concerns privately with Maxwell Rabb and others. Could he take his concerns public so long as he did not try to speak for the President? By doing so, he thought that he might be able to change the public’s perceptions, which could lead to changes in the administration’s policies.

Cain’s speeches, including one entitled "Can Freedom and Security Live Together?," were the opening round in what subsequently became known as the Cain Mutiny. "For the better part of two years I have been sitting, listening and thinking," Cain said, while admitting that, in the Senate, he had "lost sight of some fundamentals which have returned to focus during the past two years." Cain told his audience, "I am here as a proud Republican, but I am speaking as one who feels that his basic allegiance is to his Nation rather than to the political Party of his deliberate and considered choice" ("A Case Study ...").

Cain’s speeches soon came to the attention of the Justice Department and Eisenhower’s staff. A story in the Washington Evening Star, almost certainly leaked by Cain, recounted a sharp conversation between White House Chief of Staff Sherman Adams and Cain in which Adams order Cain to provide him with copies of his speeches in advance. As ordered, Cain sent copies of his upcoming March 18, 1955, speech to the National Civil Liberties Clearing House – entitled "Strong in Their Pride and Free" – to Adams and Attorney General Herbert Brownell, but not in enough time for them to do anything about it. In a note to each, he said, "I have never tried so hard to be objective and constructive in committing these views to paper. I applaud what the administration has done to improve our security systems, but I am venturing some suggestions which may anticipate future requirements" ("A Case Study ...").

But the biggest news to come out of the March 18 speech was that Cain had finally parted company politically with his longtime friend, Joseph McCarthy.

In deciding to go public with his concerns, Cain set into motion a series of events that would unfold over the next 18 months, alienating him from the President who had given him his job, leading supporters and detractors to question his judgment and motivations, and, ultimately, costing him his job.

In the beginning, as Cain told several interviewers, he felt that the logic of his arguments would bring changes to the security program by discussing the need for them within the administration. When it became obvious that, for its own reasons, the administration was not open to Cain’s suggestions, he decided to take his concerns to the public. When officials at the Justice Department impugned Cain’s motives and tried to discredit him, the battle was on. Brownell and others felt that the only honorable course for Cain to follow was to resign and continue his fight from outside the administration as a private citizen. Cain believed this argument to be "nonsense ... Had I resigned, my effectiveness would have been nil. Everybody knew this, but the critics had to say something. My views prevailed in the end and nothing else mattered" ("A Case Study ...").