Pier 55 was built by the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1900, one of the company's several piers along Seattle's central waterfront. In September 1901, a little more than a year after it was completed, the pier collapsed into Puget Sound but was quickly rebuilt and put back into service. Known originally as Pier 4 and commonly called the White Star Dock, it was renamed Pier 55 in 1944 and underwent major renovations in 1945 and 1983. Although the pier hummed with shipping activity during and after the Klondike Gold Rush, the heyday of steamer traffic on Seattle's central waterfront was brief, ending after World War I. The Fisheries Supply Company was the pier's primary tenant from the late 1920s into the 1980s. Today Pier 55 is a tourist destination, home to Argosy cruises, a coffee shop, a restaurant, souvenir and candy stores, and a popular hotdog stand.

Activity at the Foot of Spring

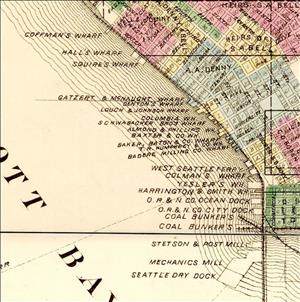

An 1889 Anderson New Guide map published before the Great Seattle Fire identified 19 piers along the central waterfront from Jackson Street north to Vine. Also on the map was a small, unnamed pier at the foot of Spring Street. When the fire spiraled out of control on June 6, 1889, everything on the waterfront south of Union Street, including the little dock at Spring Street, was destroyed. Eventually, the city of Seattle rebuilt the dock, and in February 1898 Mason County timber baron Sol G. Simpson (1844-1906) acquired the lease and operated the White Star Transportation Company (not to be confused with the White Star Line of Titanic infamy) from offices on the pier.

Simpson was already rich, but as the gold rush unfolded he saw an opportunity to make even more fabulous sums of money ferrying prospectors to Alaska. By June 1899 he had purchased at least six steamships – the Marguerite, Multnomah, City of Aberdeen, City of Shelton, Discovery, and Laurada – and in December he acquired the SS Oregon, a sleek but outdated passenger ship, for $60,000, then spent another $25,000 on improvements. In the spring of 1900, Simpson and other Seattle investors founded the Bank of Cape Nome with Simpson as vice-president and built a bank in the middle of Nome's bustling mining camp. By then Simpson had acquired more than 70 claims in the Nome gold fields and recruited a battalion of workers to dig on his behalf.

Back in Seattle, Simpson brought in a partner, steamship agent Frank A. Bell, to manage the White Star Dock and Simpson's fleet of vessels. Bell had come to Seattle from the Midwest with dreams of making his fortune and seemed to be well on his way. Simpson incorporated the Seattle Steamship Company with Bell as his partner, and in July 1899 they expanded the pier and warehouse to accommodate larger, ocean-going vessels. "The Seattle Steamship Company operating the dock has doubled the warehouse space and has spent about $1,000 in the past ten days in improving it," reported The Seattle Times on July 14. "It is now about the third in importance of the docks along the waterfront. A fine slip fourteen feet wide over which the owners claim they can load anything at any stage of the tide has been completed" ("Have Changed Docks").

With the gold rush in full frenzy, Simpson and Bell's operation reached deep into Alaska, with regular Seattle departures to Wrangel, Juneau, Skagway, Dyea, Dutch Harbor, Golofin Bay, St. Michael, and Nome. Gold seekers flooding into Seattle paid dearly for their passage and freight; most of the men were outfitted with a ton or more of food and gear. In June 1900, the 11 steamship companies operating on the Seattle-Nome route agreed to fix ticket prices at $90 for a first-class cabin, $72.50 for a second-class cabin, and $55 for second-class passage (no bed). Freight fees were set at $30 a ton for general merchandise, machinery, oats, and hay. Horses and cattle were $85 a head, dogs $20, sheep $12.50. When the Laurada sailed for Alaska on September 12, 1899, she carried only 18 passengers, but her departure was delayed for several hours to accommodate the loading. "A more general assortment of merchandise has never been sent out, and most of it goes to Cape Nome," reported The Seattle Times. "One of the last things loaded was a printing outfit consigned to Major Ingraham at Nome or, Anvil City, where a newspaper will soon be printed … A good deal of the Laurada's cargo is of a bulky nature, which makes her look as if she was loaded down. Every particle of space is utilized. The flock of sheep that are going up are cooped up in a pen built on the roof of the after cabin" ("They Are Rushed"). When Captain F. M. White finally ordered off the lines and slipped away from the White Star Dock, the Laurada and her 46 crewmen had taken on 1,200 tons of cargo.

Captain White was a popular man around the White Star Dock. Newspaper reporters sought him out for quotes about his travels in Alaska, and he was a personal favorite of Bell's. In July 1899, White "brought down with him a Siberian dog which he secured at St. Michael, and which had been brought across the Straits last winter. The dog was given to Manager Bell of the Seattle Steamship Company. It is being trained as a watch dog for the White Star dock, but the weather seems to affect it and it does a good deal of sleeping … The breed is similar in some respects to the Eskimo dog, but shows a different nationality. It is expected to keep the dock free from rats" ("A Siberian Dog").

On the Rocks

The Laurada never made it to Nome after leaving Seattle othat September day in 1899. She sprung a leak on the morning of September 28 and was run ashore by Captain White on a remote island in the Bering Sea. A Coast Guard cutter arrived to rescue the passengers and crew, but the cargo, valued at $50,000, and the Laurada, valued at $30,000, were declared total losses. Insurance covered $50,000, leaving the Seattle Steamship Company liable for $30,000. This would be the first crack in the short-lived business relationship between Simpson and Bell.

Despite the recent wreck of the Laurada, 1900 was a banner year for the White Star Dock. The Oregon was placed into service early in the year after being retrofitted at Quartermaster Harbor on Vashon Island, and the Alaska routes, particularly the Cape Nome Flyer Line, remained lucrative. The Multnomah and City of Aberdeen had become part of the Mosquito Fleet on Puget Sound, ferrying passengers to and from Tacoma and Olympia six days a week. Bell launched a new agency, F. A. Bell & Co., to lure other shipping operators to the pier, and when navigation to Alaska resumed in April, the schooner Thomas F. Bayard (Alaska Transport, Trading and Mining Co.) had joined the armada of vessels leaving for Nome. In July, the 300-passenger Charles D. Lane – owned and immodestly named by Simpson's brother-in-law, San Francisco millionaire Charles D. Lane – arrived from California to join the Alaska stampede.

Most exciting of all, the White Star Dock was scheduled to be rebuilt in grand fashion by the Northern Pacific Railroad. "Important improvements are in progress along the water front," reported The Seattle Times on June 2, "the most important one this week being the rebuilding of the White Star Dock. It will be 112 feet wide and will extend to the harbor line, 325 feet. The one-story warehouse will be 80x310 feet" ("Local Real Estate"). Demolition began two days later. "The somewhat antiquated dock property at the foot of Spring street will soon be a thing of the past," wrote the Times. "Workmen were engaged today in tearing down the old structure which has done such good service in the past to make room for the new docks. The dock will be similar to the White Star dock, and will be the second of five to be erected in that vicinity" ("New Dock Started").

The five new docks were built in accordance with Seattle City Engineer R. H. Thomson's 1897 plan for the central waterfront. Notably, the new piers were aligned at a southeast-to-northwest angle from Railroad Avenue. "Thomson's plan called for new piers … to be aligned at the same angle, preventing a recurrence of the crowding at the ends of the piers. In addition, building them at an angle instead of straight into the bay enabled them to remain in shallow water for a longer distance. This made it easier for boat traffic and permitted the construction of larger storage sheds on the docks" (Dougherty). The new White Star Dock – officially designated Pier 4 – had 750 feet of berthing space and a storage capacity of 8,000 tons. Timber pilings bridged with heavy timbers supported the platform and its thick timber decking. The shed was "of heavy timber post and beam construction, with knee bracing used to stabilize interior free-standing posts, as well as the posts within outer walls. These walls were covered on the exterior by horizontal wood siding" ("Descriptions for Piers …"). The monitor roof featured a series of multi-pane clerestory windows, allowing light into the interior. The new pier was an impressive sight, and by late July 1900 it was fully operational.

Yet as summer faded, the mood at the White Star Dock turned dark. Simpson discovered that Bell had been playing loose with company money, and on September 1 Simpson officially dissolved their business ties. Simpson then argued for relief in King County Superior Court, as reported by The Seattle Times:

"To the surprise of the business men of the city a receiver has been asked for and appointed to take charge of the White Star dock, growing out of misunderstandings incident to a verbal agreement between Sol G. Simpson and F. A. Bell. The former made the application to Judge Jacobs … and alleges that Mr. Bell has not in several important instances kept the verbal agreements that were entered into. It is claimed that Mr. Bell has overdrawn his accounts, has not done the firm's banking with the First National, to whom the firm is indebted, and that the books of the firm are not properly kept" ("King Co. Courts").

A settlement was reached in January 1901. Simpson assumed a share of the Seattle Steamship Company's obligations and was released from any further liability related to the lease of the White Star Dock. Bell was saddled with debt, including a mysterious $8,500 loan from the Capital National Bank, but now had sole control of the pier. He began promoting himself as a steamship and forwarding agent, advertising steamers for Ketchikan, Juneau, Skagway, Cape Nome, San Francisco, Tacoma, and Olympia.

Rinse and Repeat

Frank Bell was riding high by the summer of 1901. While he had lost the SS Oregon, still owned by Sol Simpson, to another dock, the steam schooner Santa Barbara began making weekly voyages from the White Star Dock, ferrying passengers and freight to Los Angeles. The steamers Humboldt, Czarina, and Ping Suey made scheduled sailings from the White Star Dock to ports in California and Alaska. The wood schooner Abbie M. Deering, made famous in the 1897 Rudyard Kipling novel Captain Courageous, began regular runs to Nome, along with the steamship Charles Nelson, which arrived from California in March to join the Alaska fleet, and the schooner Arilla. Bell also welcomed the U.S. government's business; the torpedo boat destroyer Goldsborough, and the U.S. transports Kintuck, Port Albert, and Egbert all tied up at the White Star Dock during visits to Seattle in the first seven months of 1901. On June 2, hundreds of onlookers mobbed the dock to watch the steamship Valencia and its 475 passengers sail for Nome.

In early September, Bell and his ailing wife traveled from Seattle to visit family in Minnesota. In St. Paul on the morning of September 14, they would have been blissfully unaware that back in Seattle the White Star Dock – for which Bell held a 30-year lease – had broken apart and collapsed into Puget Sound, and that, "the wharf, its contents, and all the books, records, safes and office effects of F. A. Bell & Co., lessee of the property, were carried into the bay" ("Drops Suddenly …"). Also pitched into the water were 350 tons of hay and 1,750 tons of cement, recently delivered by a freighter from Antwerp for use by local merchants. Remarkably, no one was killed, though two dockworkers, Fred Allen and George Thornton, had to run for their lives to reach Railroad Avenue before the collapse.

Bell hurried back to Seattle to face a mountain of lawsuits. A British trading firm filed suit in King County Superior Court seeking $24,347 for the loss of the cement, alleging that when the Northern Pacific built the dock, "it failed to brace or properly support the sustaining piles. This, it is claimed, made the wharf unsafe, which the defendant is alleged to have known" ("Dock Wreck Causes Suit"). Meanwhile, the Northern Pacific moved quickly to rebuild the pier. Salvage and removal operations were underway within two days of the calamity. "The hay is being hauled upon the flooring of Railroad avenue, by block and tackle, two such rigs being operated by single horses … Men are working at every point of the wreck cutting, sawing and pulling to pieces. A floating pile driver has been provided for pulling out the mass of piles. The unbroken parts of the roof are being sawed asunder so they can be handled" ("Wrecking Started").

Pier 4 underwent an expensive rebuild. The new dock "is to be made one of the best equipped and most substantial wharves on the water front," reported the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in November 1901. "The plans are for a structure 112x375 feet, partly covered by an 80x250 foot warehouse. The present site is to be filled in until the water beneath and around the dock will not exceed a depth of thirty feet at low tide. This filling is to be held in place by a dyke beneath the face of the wharf. Not so much will be needed, either, as there are 1,750 tons of cement on the bottom site of the collapsed wharf" ("Work on White Star Dock"). In a later report, the P-I wrote,

"While the fill may not rise to the surface it will at least lessen the depth of water by one-half and will effectually remove the danger such as menaced and finally destroyed the White Star dock … The menacing danger to the large docks on this part of the water front has been from the swaying caused by the waves and winds. This lessening of the depth of water will give stability not obtainable by the ordinary methods of piling" ("Will Rebuild …").

Changing Hands

The much-improved Pier 4 opened in April 1902. Bell retained the lease and lined up several "well-known shipping concerns" to operate from the dock ("White Star Dock Work"). But Bell's hold on the operation grew increasingly tenuous until a bombshell development on October 15, 1903, effectively ended his tenure. On that day, Bell, "well known in business and social circles in this city, was arrested on complaint of Charles Power, manager of the Issaquah Coal Company, who charges him with larceny by embezzlement … From June 1899 to October 1901, Mr. Bell acted as assistant treasurer of the Issaquah Coal Company. While he was on his vacation in September 1901, it is alleged by the company that a discrepancy was discovered. Upon Mr. Bell's return to Seattle … the books were experted, and the amount of the shortage, according to the company, was discovered to be $15,000" ("Charged With Embezzlement").

On the day his trial began in May 1903, Bell announced his "retirement," and the following day it was reported that the White Star Dock lease had passed to the Arlington Dock Company, a shipping agent doing overflow business next door at Pier 5 ("By One Management"). Eight major steamship lines would now operate under the Arlington Dock Co. umbrella, providing regular passenger and freight service to West Coast cities, Alaska, Asia, and Europe from piers 4 and 5. Herman Reinhart was retained to manage both piers; he took orders from Frank Waterhouse (1867-1930), whose Frank Waterhouse & Co. business empire included a fleet of steamships, Eastern Washington farms, a car dealership, coal mines, taxicab companies, the Arlington Dock Company, and many others. Waterhouse later served as president of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and was heavily invested on the waterfront.

The expanded Arlington operation went smoothly for several years, with one notable exception: In December 1903 Reinhart was arrested and charged with grand larceny after he and a Northern Pacific yard foreman were collared trying to steal a carload of wheat from Pier 4. Otherwise, business boomed. A 1906 newspaper advertisement for Frank Waterhouse & Co. highlighted the many vessels departing regularly from piers 4 and 5. The steamships Tremont, Lyra, and Shawmut journeyed to Japan, China, and Manila. The freighters Hyades and Pleiades were routed to Vladivostok, Newchwang, and Tientsin. The SS Ohio made monthly trips to Nome and St. Michael. After Waterhouse died in 1930, The New York Times noted that he had established "the first line of steamships between Puget Sound ports and the United Kingdom through the Suez Canal, and also the first cargo line from Puget Sound to Australia. He was a pioneer in the trade between Puget Sound and the Hawaiian Islands, and between Puget Sound and the Philippines. He also established the first line of steamships between Seattle and the Malay Peninsula" ("Frank Waterhouse of Seattle Dead").

When grain shipments to Asia became profitable around 1908, Pier 4 became a terminus for the Spokane Grain Company, the firm's name painted boldly on the east end of the warehouse facing Railroad Avenue. Pier 4 received an additional boost from visitors to the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. On May 3, the SS Pennsylvania arrived from Valdez, Alaska, with 80 passengers and a cargo of exhibits "including one live reindeer … Three Eskimos who mushed from a point between Nome and St. Michael with the reindeer were also passengers on the ship. They will take part in the exhibit … which will be shown at the exposition. The reindeer is a beauty and stood the trip in good shape. It is considered a representative specimen of the herd" ("Pennsylvania Brings …").

Quickly Obsolete

As lucrative as business was in the first decade of the twentieth century, it took just 20 years for Pier 4 to become obsolete as a shipping terminus. Even by 1910, most of Seattle's shipping activity had gravitated away from the city center to newer and bigger facilities at Smith Cove or in the East Waterway of the Duwamish. In 1910 the Kitsap County Transportation Company, a prominent Mosquito Fleet operator on Puget Sound, moved its operations to Pier 4, as did the Northland Steamship Company. Nevertheless, the once-bustling pier had become just a trifle in Frank Waterhouse's portfolio. By 1912 only two ocean-going vessels, the Northland and the Al-Ki, departed regularly from Pier 4.

Dodwell & Co., the Border Line Transportation Company, and the Lloyd Transfer Company were among the Pier 4 tenants who came and went in the 1910s. Waterhouse relinquished his lease during the decade, and in April 1919 the San Francisco-based McCormick Steamship Line acquired the lease and made Pier 4 its terminal for steamers carrying freight between Seattle and Northern California. "During the first year, the company's steam schooners discharged more than 150,000 tons of cargo here," reported The Seattle Times in July 1920. But McCormick's Seattle stay was brief; in 1920 the Washington Fish & Oyster Company moved onto the pier and remained there for the next 25 years. In 1928, it was joined by the Fisheries Supply Company, which would remain a fixture on the pier for more than 50 years.

The Fisheries Supply Company

Harold Jergen Gangmark (1881-1957) moved to Seattle from his native Norway in 1908, found work with the Pacific Marine Supply Company, served as its assistant manager for many years, and then went out on his own when he founded the Fisheries Supply Company in 1928 with partners George Sandstrom and C. F. Sutter. The company served commercial fishermen and canneries in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, later expanding to served wholesale and retail customers in the commercial and pleasure-boat markets.

Fisheries Supply was situated at the end of Pier 4 closest to the street, while Washington Fish & Oyster ran its wholesale seafood business from the water end. That arrangement lasted nearly two decades, until the pier underwent dramatic changes in the 1940s. First, the Puget Sound Ports Traffic Control Committee redesignated Pier 4 as Pier 55 in 1944, and in January 1945 the pier itself underwent extensive alterations "which will include cutting approximately 125 feet from the bay side … the remaining 210 feet of the structure is being remodeled to meet the needs of the Fisheries Supply Company, lessee. The Washington Fish & Oyster Company, Inc., which operated on Pier 55 for more than 20 years, has leased all of Pier 54, formerly Pier 3, and has moved to that terminal" ("Pier Alteration is Under Way").

In 1947 the Northern Pacific Railroad sold several of its waterfront holdings, including Pier 55, to an investment group fronted by Kirkland shipyard executive Albert R. Van Sant (1901-1978). Some 25 years later, Van Sant would play a key role in shaping the future of the waterfront when he refused to sell piers 55 and 56 to the city of Seattle for a proposed Central Waterfront Park. A few years later, Van Sant sold both piers to Chuck Peterson (1939-1990), owner of Trident Imports, which had its main operation on the adjacent Pier 56, and in 1983, Pier 55 underwent another extensive remodel. Two new levels were added within the pier shed, providing 7,400 square feet of office space, while the lower floor, "much of which has been vacant for some years, will be for retail tenants and a 6,000-square-foot restaurant. Fisheries Supply Co., which … has had its store on the street front, is planning to use 4,000 square feet in the remodeled area … Other returnees include a retail shop, Jonah's; a woodcarver, and a jeweler" ("Pier 55 Remodeling …"). The project also included a connecting link between the two Trident-owned piers and more room for Seattle Harbor Tours sightseeing boats.

Amid these many changes, Fisheries Supply enjoyed a long and prosperous run on the pier. After Gangmark retired in 1955, the Sutter family – first C. F., and then his son Carl – presided over the business for the next 65 years (and counting). The company displayed its products at the annual Seattle Boat Show and advertised aggressively during the holiday season. A 1968 gift guide touted the Fisco Float Coat, a waterproof, reversible jacket that doubled as a lifejacket. The following year it featured a compact, 35-pound dinghy said to be "absolutely maintenance free" and even "unsinkable" ("Gift Sensation!"). By 1972 the store was a browser's paradise with more than 12,000 nautical items in stock. When The Seattle Times published a Seattle visitors guide in 1981, it wrote, "Also along the waterfront, besides all the food and import shops, there are the oilskins, brass fittings, and other gear at Fisheries Supply on Pier 55, an occasional fishing boat unloading on the north side of the Port of Seattle pier and, of course, the ferries" ("Showing Seattle to Aunt Marge …").

Pier 55 Today

Pier 55's transition from a working pier to a tourist and leisure venue began as far back as the 1960s, when the City of Seattle, the Port of Seattle, and private pier owners commissioned John Graham and Company to create a comprehensive plan for the central waterfront. The Graham plan, submitted in April 1965, called for public investment in the redevelopment of the piers and the related infrastructure to attract private development. "The expected burst of private development did not materialize, but over several decades the waterfront slowly shed its industrial character as public amenities and private development took over the old buildings and piers and filled them with shops, restaurants, offices, parks, and an aquarium" (Ott). On Pier 55, this meant more activity for Seattle Harbor Tours (renamed Argosy in 1994) and fewer sales for the Fisheries Supply Company. In 1977 the firm moved its headquarters from Pier 55 to a new development in the Wallingford neighborhood while maintaining a smaller store on the pier until 1983. As of 2023, Pier 55 was home to Argosy's tour boats, a coffee shop, a restaurant, souvenir and candy stores, and, on the sidewalk out front, the Frankfurter, a popular hotdog stand.