When Henry Yesler (1810?-1892) arrived in Seattle in October 1852, the tiny settlement had very little going for it other than the aspirations of the few men and women who had arrived about nine months earlier. Yesler would bring them all that was needed to forge a viable community – jobs, income, commerce, and hope. Starting in March 1853, his steam sawmill on the waterfront employed almost all of Seattle's white settlers and a number of Native Americans. Many settlers also sold Yesler logs, taken from their claims or from land yet unclaimed. The following year, Yesler brought commerce to Seattle by building its first wharf. He enlarged and strengthened it over the years, and the wharf remained a major hub of the town's maritime commerce into the late 1880s. It was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1889, but Yesler quickly rebuilt a large section of it. He sold the wharf in 1890, and in 1901 it was demolished and replaced by two large wharves with warehouses, later designated Piers 50 and 51, which for decades were used by the Alaska Steamship Company. Those endured until 1982, when they were removed for the convenience of the state's ferry system.

An Intrepid Few

In February 1852, pioneers Arthur Denny (1822-1899), Carson Boren (1824-1912), and William Bell (1817-1887) canoed from Alki Point to the head of Elliott Bay in search of a better place to settle. They found and surveyed three contiguous sites that ranged along the shore from today's King Street north to today's Denny Way. Physician David Maynard (1808-1873) arrived in the spring, and Boren and Denny agreed to adjust their boundaries to allow him a parcel of land south of and contiguous to Boren's.

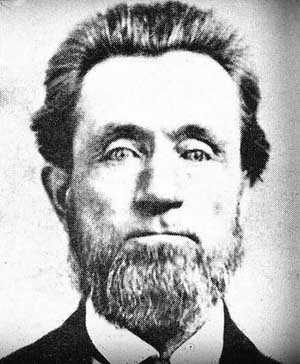

Prospects for progress were as bleak as the weather. These first settlers largely lived off the land, earning sporadic income by felling trees and selling piles, hand-squared beams, and split cedar shakes to ships that passed by. But salvation was soon to arrive, in the unlikely guise of a shaggy-haired, middle-aged man traveling alone in a canoe. This was Henry Yesler, and although he was not there first, many would later call him the Father of Seattle.

Yesler's Odyssey

In 1851 Henry Leister Yesler left his wife, Sarah (1822-1877), and a young son in Ohio to seek opportunities in the West. He was luckless in the California gold fields and soon moved north to Portland. Yesler had built two moderately successful water-powered sawmills in Ohio, and the Northwest's expanse of virgin timber was compelling. In late 1851 he contacted an old friend in Ohio, John McLain, and asked him to purchase the components of a small, steam-powered sawmill and ship them to San Francisco

By May 1852 the sawmill was on its way, and Yesler began scouting sites. On the advice of a friendly sea captain, he decided to investigate Elliott Bay, making his way to Olympia, purchasing a Native canoe, and paddling north. He reached the bay in October 1852, found the water at Alki too shallow and the point too exposed, and paddled four or so miles east to the head of the bay. After sizing up land at the mouth of the Duwamish River, Yesler followed the shoreline north to a "mere clearing in the towering forest" (Finger, 13).

Here he found just what he was looking for – deep water near shore and virgin forest blanketing the surrounding hills. There was one problem – the best location for a sawmill straddled the properties of Boren and Maynard. Yesler was about to go on his way when the two men offered him a strip of land approximately 500 feet wide that fronted on Elliott Bay and ran inland up what is now First Hill. This formed a panhandle that when cleared would lead to a 320-acre, Donation Land Act claim Yesler took for himself and his wife. Trees harvested from that claim and other sites could be skidded down the panhandle to the waterfront on greased logs. The strip was informally called Skid Road, first appeared on maps as Mill Street, and later became Yesler Way. Boren and Maynard's sacrifice was "the first exhibition of civic enterprise given by the community" (Beaton, 6). [Note: At least one source holds that Yesler purchased the strip of land, but this seems to be a minority view].

News traveled fast. An untitled note published on October 30, 1852, in The Columbian newspaper of Olympia read in part, "Huzza for Seattle! It would be folly to suppose that the mill will not prove as good as a gold mine to Mr. Yesler, besides tending greatly to improve the fine town-site of Seattle, and the fertile country around it, by attracting thither the farmer, the laborer, and the capitalist. On with improvements! We hope to hear of scores of others 'ere long" (The Columbian).

On the Waterfront

Yesler sailed to San Francisco to arrange the shipment north of the mill equipment. Before leaving, he built a log cookhouse for the mill that for several years was the center of the community's social and civic activities. It was also Yesler's home, shared with a Native American woman named Susan (with whom he fathered a daughter, Julia) until he was joined by Sarah in 1858 (their son, George, had died earlier that year).

While Yesler was in California, other settlers began building a roofless, open-sided shed on the bay's shore to house the mill, its western end supported above the water on pilings. Years later Yesler recalled the equipment's arrival:

"In unloading the machinery for the mill we had to throw it all into the water & let it float ashore. The boiler was floated in this way, but the engine was placed on a raft. After the establishment of the mill which was commenced in '52, the town grew rapidly" ("Henry Yesler and the Founding of Seattle," pp. 273, 275).

In the 1850s, Elliott Bay extended farther inland. Much of the ground near Yesler's mill was marshy, and just south of his cookhouse a sodden, low-lying band of land called the Neck led to a small peninsula that during very high tides became an island. East of the peninsula was an unusable tidal lagoon. Once the mill was operating, Yesler filled the lagoon and marshy areas with sawdust and other mill debris, the first efforts of a decades-long struggle to make Seattle's waterfront more useful for commerce. As time passed, the refuse of other mills and other industrial concerns filled additional areas, but it was not until 1936 that the city's first seawall was completed.

Yesler's First Mill

In early 1853 the mill equipment was installed in the shed, which was finished with some of the saw's first product. The machinery had three main parts – a 12-horsepower steam engine, a boiler to produce the steam, and a 48-inch circular saw. A millpond to the north held the harvested raw logs. After running through the saw, the lumber slid down an inclined ramp into Elliott Bay, and that which wasn't used locally was rafted up and delivered to ships waiting offshore. Yesler's Native American employees, who lived their entire lives in close communion with the saltwater and had no fear of it, were particularly adept at this operation.

Yesler's was not the only steam-powered mill on Puget Sound for long. Others soon appeared in other locations, larger and more technically advanced. Given his equipment's limitations, Yesler often had to mill short logs of inferior quality, producing some lumber that even he characterized as "cultus," a Chinook Jargon word meaning worthless or nearly so. This was used for sheds, fences, and the like, but he also produced enough good product to replace the first settlers' rudimentary log cabins with more substantial frame houses, to supply the local market as the town grew, and for export. When demand was high, the mill operated 24 hours a day in two 12-hour shifts, and its products were shipped to as far as Hawaii and Australia.

Upon Yesler's death in 1892, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer republished an interview from about a decade earlier in which he recalled the mill's earliest days and its immediate impact on the small and struggling settlement:

"[A]fter I got my mill started in 1853, the first lot of logs were furnished by Dr. Maynard. He came to me and said he wanted to clear up a piece on the spit, where he wanted to lay out and sell some town lots ... "

"My mill in the pioneer times before the Indian war furnished the chief resource of the early citizens of the place for a subsistence. When there were not enough white men to be had for operating the mill, I employed Indians and trained them to do the work ... Arthur A. Denny was screw-tender in the mill for quite a while; D. T. Denny worked at drawing in the logs. Nearly all the prominent old settlers at some time or other were employed in connection with the mill in some capacity, either at logging or as mill hands ("House of Mourning").

Despite its shortcomings, the importance of Yesler's mill to early Seattle and King County cannot be overstated. It was the settlement's first industry and its first employer. In the words of one historian: "Yesler's mill did not create the town, yet it did more than any one thing to fix the seat of the place. As the first steam mill, and the first mill of any capacity, it gave a temporary advantage to the town, placing the means of building decent houses and establishing pleasant homes within the reach of the people. The effect of this in fixing the people here was very great" (Grant, 243).

The original mill stood for 15 years, but needed increasing amounts of upkeep and repair. In 1868, Yesler bought out all his partners and built a new and larger mill nearby. One early city historian noted:

"H. L. Yesler built a new sawmill this year. The first sawmill stood on Yesler Way east of the present Post Street, the original beach. The new mill was in the rear of the old one, or to the west of Post Street. When it was completed the old one was torn down, and on its site were erected a number of one-story buildings used for many years by the post-office, by bakers, butchers, grocers and others in their various lines of business" (Prosch, 189).

The equipment from the old sawmill was put to work in Yesler's grist mill.

Yesler's Wharf

Rafting lumber out to ships anchored in deep water was not optimal, and Yesler soon racked up another "first." In late 1854 he built a makeshift pier that extended a short distance into Elliott Bay. The first steamship to dock there was the sloop-of-war USS Decatur, in the winter of 1855-1856. The ship needed repairs, but the pier was found to be "not of sufficient strength ... to land the battery [large cannon or group of cannons] of the ship" (Finger, p. 328, note 2). And it had a further limitation, being neither long enough nor strong enough to accommodate large, deep-draft ships. Still, for a time, it was the only game in town.

Yesler's company soon comprised four interrelated businesses – the mill itself, a grist mill, a company store, and most important, Yesler's Wharf. Between 1856 and 1868 he had eight different partners involved in various of his businesses. These were rarely happy alliances; early court records are replete with lawsuits in which Yesler was either the plaintiff or the defendant.

In March 1859, Olympia's Pioneer and Democrat reported that "a wharf to deeper water is being constructed by Mr. H. L. Yesler," ("Seattle") using a steam pile-driver brought up from California. Much of the wharf was built on fill, and after the pilings were driven, Yesler reinforced the structure by dumping more rocks, ballast, lumber slabs, and sawdust between them. In 1884 an excavation for a new sewer revealed details of the wharf's construction: "The surface is composed principally of sand and gravel, which is underlaid by earth three or four feet deep, then sawdust to the depth of two or three feet, and slabs, stringers and piles from there to the bottom." Whether Yesler intended it or not, the fill brought a benefit in addition to strength. The condition of the slabs in 1884 provided proof "that the toredos had not operated away from the wooden edges of the wharf" ("Solid Roadway").

Toredos are saltwater worms that feast on submerged wood, as another early Seattle entrepreneur would learn, to his regret. In 1858 Charles Plummer (?-1866) built a two-story structure just two blocks south of Yesler's mill. He sold dry goods, groceries, and hardware, and the upper floor was used for dances and meetings. There was a bowling alley in the basement, and he soon added a small wharf, which put him in direct competition with Yesler. As the Seattle Post-Intelligencer later wrote, "Every steamer landing at Plummer's wharf was a dagger thrust into Yesler's breast; every boat landing at Yesler's wharf caused sleepless nights to Plummer" ("Plummer Wharf Goes ..."). But Plummer didn't use fill for his wharf, and it soon collapsed, brought down by voracious toredos. Yesler's waterfront reign was safe for quite a few more years.

The next extension to Yesler's Wharf came in 1875, prompting Seattle's Weekly Intelligencer to note that "Yesler has often been credited with having a 'mania for wharf building'" (Finger, p. 298). The wharf now included large bins for coal brought by rail from nearby mines. As the wharf moved incrementally farther into Elliott Bay, Yesler added buildings as he went. He would extend and enhance it frequently, and the wharf eventually became a sturdy, multi-faceted structure nearly 1,000 feet in length that berthed ships of all sizes and housed multiple businesses. When the main structure had been extended as far into Elliott Bay as was feasible, Yesler added a dogleg pier that roughly paralleled the shore, with a huge warehouse at the end, giving the whole wharf a rough Y shape.

By the late 1880s there were other substantial wharves on the waterfront, but "Yesler’s Wharf was, by far, one of the largest and most important piers and the waterfront was becoming an important transportation hub" ("Central Waterfront and Environs ...," 9). Although there are few detailed accounts, it seems certain that Henry Yesler made much more money from his wharf than he ever did from his mills. He wasn't a great businessman, and loaned money too freely; most of his late-life fortune came from the sale or development of properties on his and Sarah's claim.

The First Big Fire

On July 26, 1879, a fire started in Room 12 of the American Hotel, a low-cost hostelry near the shore of Elliott Bay on Mill Street, very close to Yesler's mill and wharf. It was the city's first major fire, and it quickly spread in every direction. Nearly 125,000 square feet along the waterfront was destroyed, including Yesler's second mill, which had been leased to James Murray Colman (1832-1906). Yesler still owned his wharf, however, and a substantial portion of it, along with the lumber stored there, was destroyed. The flames took "everything between Washington Street and the mill cookhouse from the alley west to the Cottage by the Sea saloon. It was a good deal the worst fire that ever devastated any part of Washington Territory" ("Seattle in Ashes").

Colman decided to site a new mill at a different location, and in 1881-1882 Yesler built his third mill, entirely on his wharf. On December 23, 1887, it too burned, in a fire that started in a cigar store at about 10:30 p.m. The value of the mill and equipment, both total losses, was estimated at $15,000. Yesler had no insurance, telling a reporter on December 28, "No, the rates are so high that I prefer to carry my own risk. I can afford to be burned out occasionally ..." ("The Philosophical Manner ..."). But this time Yesler apparently had had enough, and didn't rebuild the mill. He still had the wharf, which had escaped the flames relatively unscathed. Less than two years later, it also would be lost to fire.

The Great Fire

When the Great Seattle Fire wiped out most of downtown Seattle and the waterfront on June 6, 1889, Yesler's most painful loss may have been the complete destruction of his huge wharf, the last surviving signifier of the essential role he had played in the city's earliest days. He was not an unsentimental man, but at nearly 80 years of age it would have been understandable had he chosen to rest on his laurels. Instead, before the ashes had cooled, he began to rebuild.

The wharf's pilings had burned to the waterline, and work began at once to cap and extend the charred stumps, and to put down new decking. It went quickly: "In little more than a week after the fire passengers and freight could land there. By the first anniversary of the fire he had rebuilt a part of the wharf 460 by 220 feet in dimension and raised about eighteen buildings on it" (Finger, 312), at an uninsured cost of about $75,000. The new pier extended over what had been the now-unneeded millpond. Even so, it was less than half the size of the one destroyed. But Yesler again had made a timely contribution to Seattle – much of the lumber needed to rebuild the ravaged city was landed at Yesler's Wharf.

Henry Yesler had much else on his plate. His commercial properties in downtown Seattle also had gone up in flames, including the ornate Yesler-Leary Building, finished in 1883. His beloved wife died in 1887, and in early 1890 he visited Ohio, returning with a new wife, his young second cousin, Minnie Gagle (1868-1973). This created a scandal in some quarters, which Yesler simply ignored, but he decided it was time to divest himself of the wharf and associated property. In August 1890 he agreed to sell it to Alanson S. Dunham and his wife, in their individual capacity, for $175,000. Dunham was the managing trustee of the home-grown Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway, which was later to become a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific Railway (which Yesler hated). According to one scholar, it was "understood that he [Dunham] was acting as agent for the larger railroad" (Finger, 314). Arcane and impenetrable were the ways of railroad men in that age.

The last payment was made in March 1891, and for the first time in nearly 37 years there was no wharf on the city's waterfront that belonged to Henry Yesler. But the centrality of the one he built remained – two months later, U.S. President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901) landed at Yesler's Wharf, just as former president Rutherford B. Hays (1822-1893) had done 10 years earlier.

The End of Yesler's Wharf

The Northern Pacific made use of Yesler's Wharf until 1901, when it was razed and most of the fill removed. It was replaced by two large piers, one near the north border of the property and one near the south border. An 1897 replat of Seattle's tidelands by City Engineer R. H. Thomson (1856-1949) required that all piers be rebuilt based on a northeast-southwest alignment, and also imposed a new system of designations.

The Oregon Improvement Company had labeled its piers south of Yesler's with the letters A and B, and these were left undisturbed. But all those north of Yesler Way, previously known only by names, were assigned numbers, and the Northern Pacific wharves were designated Pier 1 and Pier 2. For many years they were used by the Alaska Steamship Company, which had flourished in the boom that followed the 1897 Klondike Gold Rush and would eventually enjoy a near monopoly of freight and passenger service to Alaska.

Numbers Game

Seattle's waterfront continued to mature during the twentieth century, but Thomson's letter-and-number system remained undisturbed until 1944. During World War II, Puget Sound was home to dozens of arms manufacturers, shipyards, and military bases. Several Elliott Bay piers (and those on the industry-heavy Duwamish Waterway) were used for military purposes. Thomson's designations did not extend south beyond the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company's Pier A, four wharves down from Piers 1 and 2. Worse, his system had not been strictly enforced; many piers, although assigned numbers, were still known almost exclusively by the names of the companies that built, owned, or used them.

On May 1, 1944, the Puget Sound Ports Traffic Control Committee rationalized the pier designations by imposing a progressive numbering system that covered all the piers and docks on Elliott Bay, starting in West Seattle and moving east and then north. The numbers 1 through 24 were assigned to West Seattle and Harbor Island, and numbers 25 through 49 applied to those south of Northern Pacific's Piers 1 and 2. From there the numbering progressed north around Elliott Bay to end with the U.S. Navy's Piers 90 and 91 at Smith Cove. (Freight terminals on the Duwamish River above Harbor Island were given numbers greater than 100).

The two piers on the former site of Yesler's Wharf became Piers 50 and 51, over the protests of Alaska Steamship, which had enjoyed the prestige of the easily remembered Piers 1 and 2. But the objections soon gave way to the exigencies of war; many of the company's ships were mobilized for the Allied cause, with five sunk by hostile action. The line stopped carrying passengers in 1954, then became a pioneer in containerization. Piers 50 and 51 were still used for maritime commerce through 1961, but things would change with the coming of Seattle's Century 21 World's Fair.

In December 1960, with preparations underway for Century 21, Marfran Inc. closed a deal to purchase Piers 50 and 51. Within a month, a subsidiary company, Seattle Piers, had torn down the warehouse on Pier 51, improved the deck, and built the Polynesia Restaurant on the end, which was leased to restaurateur Dave Cohn. The rest of the wharf was used as a 300-car parking lot. The warehouses on Pier 50 were next to go. The original plans called for commercial development, with an aquarium, 30,000 square feet of commercial space, a 40-unit motel, and a heliport. The gap between the two piers was to be decked over, but this plan was abandoned in favor of a connecting bridge.

Then someone had a better idea.

Pier 50 Gets a Monarch

The combined cargo/passenger ship Dominion Monarch was launched in England in 1939 for use on the Britain-to-New Zealand run. At 650 feet long and with four-screw propulsion, the ship set a number of records for size and power. More than 500 passengers all had first-class, air-conditioned accommodations, tended to by a crew numbering more than 380. The Dom, as the ship came to be called, served as a British troopship from 1940 to 1947, then returned to normal operations from 1948 to 1962. Its useful life over, it was headed for the scrap yard.

That fate was deferred when the Dominion Monarch was leased for use as a floating hotel during Century 21, moored to the south side of Pier 50. When crew quarters and some cargo space were converted to passenger cabins, as many as 1,450 visitors could be housed. As it turned out, that was more than was needed, and it stopped accepting guests several weeks before the fair ended. On November 25, 1962, the Dominion Monarch arrived at Osaka, Japan, to be broken up for scrap.

The End

In 1963, Ye Olde Curiosity Shop moved into a new building on Pier 51 that was designed by Paul Thiry (1904-1993), the principal architect of the world's fair. It resembled a Native American-style longhouse, and shared the pier with the Polynesia Restaurant until January 1982, when the Polynesia was lifted onto a barge and towed to storage on the Duwamish West Waterway. Ye Olde Curiosity Shop would remain in place until 1988, when it moved to Pier 54. Piers 50 and 51 were then demolished to accommodate the growing requirements of the Washington State Ferry System.

All that remains of Henry Yesler's Wharf, so essential to the growth and prosperity of Seattle, is a bronze plaque placed in 1964 that reads, in part: "SEATTLE'S FIRST PIER LIES BURIED BENEATH YOUR FEET."