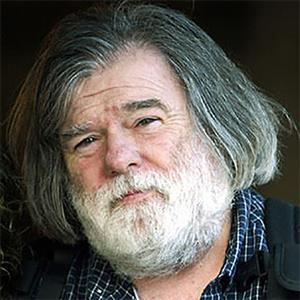

Grant Haller (1944-2017) worked for 40 years as a newspaper photographer in Everett and Seattle, his career starting with Vietnam War protests and ending only when the Seattle Post-Intelligencer folded in 2009. "He was the genuine article," wrote P-I colleague Susan Paynter. "Abundant talent, the eye of an artist and the heart of an open hearth, plus always a wink of whimsy." This look at Haller's life was written by Mukilteo historian Steve K. Bertrand, a longtime teacher and coach in the Everett School District and an award-winning photographer.

Beginnings

Grant Haller was born on December 2, 1944, in London. His parents had met during World War II. Meredith Edgar "Ed" Haller was an American GI, and Doreen "Micky" Mead was British. They lived on the outskirts of London. The Hallers had three children – Brian, Grant, and Mary. Following the war, they moved to the United States and settled on Seattle’s Queen Anne Hill. The Hallers were from a long line of fishermen. At the turn of the century, Hallers had cast their nets in Port Angeles. Ed Haller continued the family tradition at Fishermen’s Terminal in Seattle.

Grant Haller attended Queen Anne High School, graduating in 1963. Inquisitive by nature, he was drawn to what was happening in the world. This was reflected in his love of the outdoors. He was also intrigued by photography; during his high school years he could often be seen lugging around a 4-by-5 box camera. Following high school, he attended Everett Junior College, where he continued his passion for photography. During this time he met Mary Dorman, on the waterfront in Edmonds, and they soon began dating. Grant was drafted into the Army, and because he was one of the few guys who could type, he was stationed at Fort Lewis. This saved him from going to Vietnam. After his two-year hitch, he left the military in 1968. He and Mary married and settled in Ballard. Their son, Pat, was born in March 1969. Haller returned to school at the University of Washington, and while pursuing his degree, he worked as a stringer (freelance journalist and photographer) for The Daily, the college newspaper, and delivered afternoon newspapers for The Seattle Times. It helped make ends meet. He graduated with a degree in communications from the UW in the spring of 1970. Their daughter, Shelby, was born in November 1971. Another daughter, Rory, followed in November 1976.

Grant had worked for the Everett Herald from the spring of 1969 to 1971. He’d then taken a job as a stringer for The Seattle Times. In 1974, the Haller family moved to Lynnwood, right off 164th Street. Grant worked at the Times until 1976, when he took a job with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (P-I). The paper had been founded in 1863. Originally, it was the weekly Seattle Gazette. The P-I was owned by the Hearst Corporation. Its building had the iconic, spinning globe affixed to its rooftop. Thus began Haller's 33-year career with the P-I.

The Haller kids attended Alderwood Junior High. Pat turned out for track his eighth-grade year. His running abilities caught the eye of Lynnwood High School coach Ernie Goshorn. But it was on a summer, eight-day, 70-mile Boy Scout hike in the Cascades that some of the guys finally talked Pat into running cross-country at Lynnwood High School in the fall of 1983. A Lynnwood harrier named Eric Hruschka had won the state Class 2A cross-country title the previous fall. Pat felt he could beat him. Turns out, Pat’s intuitions were accurate. He claimed the 2A state cross-country championship in 1985 and 1986. He also won the 3,200-meter championship in track & field in the spring of 1986, as well as a 1,600-meter title in 1987. Pat went on to run at the University of Oregon, where he qualified for the national cross-country championships four years in a row and was a five-time All-American. When possible, Grant was at Pat’s races taking photos.

The 1970s

Meanwhile, Grant was like a hound dog to scent, sniffing out stories wherever they hid for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. His work in the 1970s included everything from Vietnam War protests to the Sky River Rock Festival, Seattle Liberation Front demonstrations, the Satsop River Fair and Tin Cup Races, the People’s Coalition for Peace and Justice marches, anti-McGovern protestors at Boeing Field, the Crabshell Alliance protests, marchers protesting infringements on Native fishing rights, Reverend Jesse Jackson’s visit to Seattle, Dixie Lee Ray, Henry Kissinger, and Saint Patrick’s Day Parades. He even covered a parachute drop during filming at the Space Needle on November 19, 1977.

The decade ended on a high note when the Seattle SuperSonics defeated the Washington Bullets on June 1, 1979, to claim the NBA Championship. And while fans crowded the streets celebrating enthusiastically, Haller snapped photos with his camera of the joyous moment. "Dad was relentless in his pursuit of a story," said Pat Haller. "Through his photography, he had a unique ability to capture life in the Pacific Northwest. Furthermore, when he went on a photo shoot, he didn’t just take one or two pictures, he’d shoot hundreds. Then, dad brought the photos home and developed them in his dark room."

Mount St. Helens and the 1980s

Haller furthered his reputation as a master visual storyteller in the 1980s, beginning on May 18, 1980, when Mount St. Helens erupted. Adventuresome by nature, Haller was able to take a legendary photograph depicting the colossal power of the eruption, made possible by a teenage pilot under the influence of cannabis. Haller had gotten word of the eruption and quickly drove to Seattle’s Boeing Field. He got in touch with a pilot he knew and the guy agreed to take him up. The pilot, Salty Roark, liked working with the P-I photographers because, he said, "They weren’t afraid to die."

Roark, who had been smoking pot prior to the flight, a P-I reporter, and Haller took off in a four-seat plane and flew toward the erupting mountain. To avoid trouble with the FAA, Roark turned off his transponder as they got close to St. Helens. As the engine sputtered through the ash plume, the only words Haller remembers the young pilot uttering were "Wow!" Haller was busy snapping photos – there was a story to be told. Afterward, he was relieved when the plane returned safely to the ground. His photo of the eruption was iconic; it garnered numerous awards and was selected as the P-I's "Photograph of the Millennium." Roark, for his troubles, was fined $10,000 for flying too close to an erupting volcano.

The rest of the 1980s were filled with a myriad of assignments, among them the Pike Place Market Street Fair, the Seattle Coalition Against Apartheid demonstrations, the Bite of Seattle, fashion models in downtown Seattle, Ronald Reagan’s campaign in Seattle, MLK Day remembrances, Memorial Day parades, the Metro Transit bus tunnel construction, housing protests, the Rolling Stones at the Kingdome, and the 3,397-mile TransAmerica Bicycle Trek from Seattle to Atlantic City to raise money for the American Lung Association. "Dad covered everything from the mundane to the biggest events," said Pat.

One interesting story photographed by Haller was the Donut House. Located at 1st Avenue and Pike Street in downtown Seattle, across from Pike Place Market, the Donut House was a popular eatery. It was also a popular gathering place for street people and runaway teens. In 1979, a youth had died during a stabbing in the doorway. Rumor had it many of the teens were involved in prostitution. In October 1979, a crime task force raided the establishment. The store operator, Guenter Mannhalt, allegedly had been dealing drugs. He was also purported to be the mastermind behind several robberies of restaurants in Seattle and Bellingham. His donut-shop employees had committed the robberies and testified against him. Mannhalt was convicted in November 1981 and the Donut House lost its lease.

Here, There, Everywhere

The life of a photographer involves a lot of hustling. Haller was either hustling to photograph a story, hustling to develop the photograph, hustling to get it accepted by his editors, or hustling to meet the paper’s deadlines. This involved being ready at a moment’s notice. Celebrity weddings. Oil spills. Goodwill Games. Husky football. WTO riots. Dancing Ivar’s clams. Press conferences. Visiting presidential candidates. Final Four. Beauty pageants. Spring training. Chelan fires. Sonics basketball. Seafair parades. Whatever the occasion, Haller was there with his Nikon camera. Pitching photos to The Associated Press, United Press International, Reuters, etc. Relentless. "Dad was always hustling to get his photos out," said Pat. This dogged pursuit of a story, and his willingness to fight for his stories, earned Haller the title "The Lion of the Newsroom" at the Post-Intelligencer.

During his time at the P-I, Haller also became involved in promoting the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA). The organization, established in 1946, is made up of editors, television videographers, still photographers, and journalism students. Its headquarters are in Durham, North Carolina. Haller served as president. An NPPA award winner, he remained a tireless director and promoter of the association.

Family Vacations

Family vacations always involved Grant bringing his camera. "Vacations were always an adventure!" laughed Pat. "We’d go to Rhode Island so dad could photograph the America’s Cup. Or we’d go to Cheney in the hundred-degree heat and dad would photograph the Seahawks at training camp. Or we’d go to the Tri-Cities so dad could photograph hydros on the Columbia River. Or we’d be in Sunnyside so dad could photograph the eclipse."

Pat recalls a family vacation to the Gettysburg Battlefield. "We had to arrive early at Gettysburg for the morning light. Then, we had to come back that evening so he could photograph the battlefield at dusk. The lighting had to be just right."

Through high school, college and post-college, Pat often accompanied his dad. They worked together. "My dad would shoot photos of various events and then I would run the film back down to the P-I," said Pat. He has many fond memories. Seahawks, Sonics, Mariners. One time he split a submarine sandwich with ESPN’s Brent Musburger in the press box during a Mariners game. "From the '70s to the 2000s, if it was a newsworthy story in Puget Sound, my dad was probably around it," recalls Pat. "This involved everything from bank robberies to the Kingdome being blown up." Pat theorizes that his dad's enjoyment at covering the Sonics had something to do with the free buffet meal before each game.

A Lesson in Humility

Pat told the following story: "My father had just gotten home from the front line in Iraq with the USS Abraham Lincoln crew, and his next assignment was photographing a bowl of noodles in a Thai restaurant that had just opened in Seattle. Boy, did that make him mad!" laughed Pat. "Dad did a great job covering the people who make a story ... Whether it was a concert, sporting event, festival, parade or political event, dad would shoot hundreds of pictures. Then I’d do my thing – run the film back to the P-I to make deadline. What didn’t find its way into the newspaper, dad often published in an on-line collage of 30-40 photos."

When he went out on assignment, Grant would often drive his 1992, three-cylinder, red Geo Metro with no AC to Boeing Field and catch a helicopter to events. Pat laughs recalling his father, 5 feet 10 and more than 200 pounds, getting into that small car. "It definitely leaned to one side when he got in! That Metro sure took its share of abuse."

The 1990s and Beyond

The 1990s found Haller immersed in more newsworthy events. Never a shortage of stories to capture. There were marchers supporting the troops in Iraq. Tent City at the Kingdome. Dale Chihuly. Northwest AIDS Walk. Blue Angels. Boeing. Everett’s Sam Bloomfield. Bill Clinton campaigning at the Pike Place Market. As a matter of fact, Haller's photo of Clinton was so striking, the White House ordered 50 copies. Then there was that double by Edgar Martinez, scoring the Mariner’s Joey Cora and Ken Griffey Jr. to clinch the American League Division Series over the New York Yankees 3-2 on October 8, 1995. And though Bill and Melinda Gates’ wedding was hush-hush, Haller captured it all. Always, the pursuit of the story within a story. Of his work, Grant once said, "I’ve always thought that when I went out on an assignment that I was the eyes of 250,000 people."

May 1, 2003, found Grant aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier at Whidbey Island during the Gulf War. The crew had just completed their 10-month mission in Iraq. President George W. Bush came aboard. Haller was present when Bush informed the crew, "Mission completed." The Millennium brought with it other newsworthy events. In 2006, Haller photographed Senator Barack Obama in Seattle while on the campaign trail. "Dad’s ability to see forward to the end of a story while in the midst of it was uncanny," said Pat.

One story Haller felt compelled to tell concerned the Makah Indian Nation. Again and again, he made the trek to Neah Bay. "Because of the Haller family ties to fishing, my dad was very sympathetic to the whaling plight of the Makah,” said Pat. The Makah are the only tribe in the United States with a guaranteed right to hunt whales. However, since commercial whaling almost wiped out the whale population, the Makah had not whaled since the 1920s. When the gray whale was removed from the Endangered Species list in 1994, the Makah announced they would resume their treaty right to pursue whaling. This stirred bitter protests amongst animal rights activists. It became an issue of Indigenous rights versus animal rights. For the first time in over 70 years, the Makah returned to hunting whales. Like he’d done his entire career, Haller waded right into the middle of the issue with his camera, capturing the moment.

End of an Era

The 146-year-old Seattle Post-Intelligencer closed with a final edition dated March 17, 2009. Evidently, the Hearst Corporation finally lost patience when losses totaled $14 million in 2008. Amongst a staff of 167 members, Grant was the P-I’s longest-serving employee at 33 years (1976-2009). He stayed to the end. "Given the chance, they’d have had to bury dad in that spinning globe at the P-I," laughed Pat. Grant was heard to say at the closing of the P-I – "I guess what I’ll miss most about the P-I is this great view of Elliott Bay from my office window." The P-I went online for a couple years, kept alive by a handful of P-I folks.

Following retirement, Grant enjoyed time spent with family and friends. The Pacific Northwest remained his playground till the end. He’d been an avid hiker of Northwest trails. He’d worked ski patrol at Snoqualmie Pass. He’d mingled with the fishermen at Ballard Bay. Grant’s adventurous career had taken him to the air, land, and sea. Later in life, his grandkids were a joy. Pat’s son, Miler, had taken to distance running like his father. One of Washington’s best harriers, Miler was a 2-time All-American at Boise State while earning an MBA. Grant photographed Miler’s races just as he’d once done Pat’s.

Grant Haller died on July 26, 2017, in Edmonds. He’d been fighting heart illness and interstitial lung disease. He was surrounded by his family. It was said of Grant, "He was a beloved husband, father, son, brother, uncle, grandfather, great-grandfather, and journalist." His death stirred a deep sadness among family, friends, and Seattle’s media folk. He was described as "the greatest storyteller in a house full of storytellers." Furthermore, Grant was quite a presence in his own family. "There was a pretty big void when he left," said Pat.

Haller received numerous awards and honors during his career. A photograph of soccer legend Pele had earned Grant honors as the AP Sports Photographer of the Year. Besides being an NPPA award winner, he had been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize on numerous occasions. But more important, the Pacific Northwest’s Grant Haller captured the essence of a time, place and people during his storied career as a photographer. It had been unflagging work; fortunately newspapers and photography were Grant’s passions.

After his death, Grant’s family had a decision to make: What to do with a lifetime of photographs? Mary Haller and family decided the best course would be to donate Grant’s photos to the University of Washington’s Special Collections department. That way they would be preserved and enjoyed by all. This was no easy task; Grant had spent his career cataloging photographs three different ways – by date, person, and event. There were 40 file cabinets full of photos. "Dad never threw anything out," said Pat. On November 13, 2018, the family sent two full vans to the University of Washington, loaded with Grant’s photos. So many wonderful stories, so many wonderful memories.