This history of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) in Washington state was written by A. J. Burton, president of the Seattle chapter.

The Ancient Order of Hibernians

Irish organizations appeared in Washington after 1880. The Ancient Order of Hibernians was established in 1890, and it was one of the largest Irish nationalistic organizations. The Irish Rebellion of 1917 increased interest in Irish social, nationalistic, and religious organizations among some of the Irish in Washington state.

In 1917, the state president of the AOH, Rev. John E. O'Brien of Everett, sought to institute a course of Irish history in the parochial schools of the Diocese. In 1921, a Celtic Cross Association was organized out of the Ancient Order of Hibernians to assist the Irish in Ireland with social relief.

Hibernians versus Bishops

The Ancient Order of Hibernians and the bishops of Seattle maintained a tense relationship. In 1924, Bishop O'Dea declined a Hibernian request that St. Patrick's Day celebrations be made their sole responsibility. O'Dea held that asking the pastors to forgo their parish entertainment on St. Patrick's day "would diminish, if not greatly endanger, the interest in the day we celebrate with so much pleasure and spiritual profit."

In 1939, the Hibernians and Bishop Shaughnessy discussed who would handle arrangements for the visit to Seattle of the Premier of Ireland, Mr. Eamon de Valera. Bishop Shaghnessy resisted Hibernian efforts to run anything that took place in parishes or on a diocesan level, including Irish nationalistic activities at the beginning of World War II.

Anti-Catholic Sentiment

The Irish in Washington who still identified themselves as Catholic in some way were affected during the early twentieth century by growing anti-Catholic sentiment in Washington. Groups in Seattle set out to "rid the school boards of Catholics."

In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan held rallies in Tacoma and Issaquah. This group, noted for its campaign for white Protestant supremacy, promoted Initiative 49, an anti-private school bill. While defeated by nearly 60,000 votes, more than 131,000 citizens voted for the initiative. Among Catholics, this opposition and bias increased a sense of Catholic identity.

After World War II

Irish social organizations continued to exist during the war and in the post-war years. The Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick was a non-sectarian organization that held an annual meeting and banquet on St. Patrick's Day. Three quarters of the membership was Catholic. Another group, known as the St. Patrick's Society, succeeded and failed in the space of four years. Its primary purpose was to provide an annual program to honor St. Patrick.

A new Archbishop, Thomas Connolly, improved the relationship between the archdiocese and the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Connolly provided a chaplain to the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians, assigning them the service work of assisting the St. Peter Clavier Interracial Center. The AOH itself however was declining in membership.

Gaelic American Club

In 1953, recent immigrants from Ireland formed the Gaelic American Club. The club's purpose was to support new emigrants from Ireland to Washington state. It took over the functions the AOH and its auxiliary had performed in earlier years. Bishop Shaughnessy named Fr. William Treacy as its first moderator of the club.

The 45 immigrants were not sufficient to maintain a club and so it was opened to Irish-Americans as well. As the organization grew, the Ordinaries became concerned that it would compete with other Catholic social organizations such as the Catholic Daughters of America, the Young Ladies Institute, the Knights of Columbus, the Foresters, and others. In 1956, Archbishop Connolly wanted the club to "isolate and cut (the Irish) from the general current of life in the community."

By 1959 the club was being called the Irish-American Society, and persisted into the 1960s.

Irish Nationalism

Between 1948 and 1955, the Irish Information Bulletin, a politically motivated national publication which called for a unified Ireland, sought sponsorship for a Washington Chapter. Bishop Shaughnessy and Connolly were in favor of a unified Ireland, but did not want this sort of political organization in Washington.

Washington's Irish did not appear to participate in Irish nationalistic activities in any institutionalized manner. Memberships in Irish ethnic organizations therefore declined by the end of the 1960s.

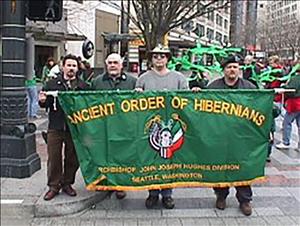

Many of today's Irish and Irish-Americans living in Seattle belong to one of the area's many Irish cultural or heritage societies. The Seattle Irish Heritage Club is the most popular. They also continue in the strangely Seattle Irish tradition of ignorance, and obstructionist efforts concerning the human rights issues of Northern Ireland. The exceptions to these are the Seattle chapter of Irish Northern Aid, and the renewed Division of the Ancient Order of Hibernians.

Mobility and preoccupation with economic achievement leached much institutional religious affiliation out of many Protestant and Irish Catholics in Washington state.

The Irish and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church in Washington played a role in promoting Catholic and Irish identity during the twentieth century. Four of the seven Ordinaries of the continuous diocese in Washington have been Irish-American, beginning with the third bishop of Seattle, Edward John O'Dea, ordained bishop on September 8, 1896. O'Dea moved the See of the Diocese of Nesqually from Vancouver to Seattle in 1903.

Seattle, however, had very few national parishes. Though Irish were associated with particular parishes in the diocese at various times: St. Michael's Parish in Olympia, Holy Rosary Parish in Seattle, St. Patrick's in Tacoma, St. Aloysius in Spokane; these associations had more to do with residential patterns and movements in these cities than with any organized goal toward the creation of national parishes.

The interactions of Irish organizations such as the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Friends of St. Patrick, and the Gaelic-American Society with Bishops O'Dea and O'Shaughnessy and with Archbishop Connolly reflect the delicate balance between ecclesiastical leaders, the local Irish Catholic community, and their pro-American sentiments.

Irish and Irish-Americans came to Washington with aspirations for a better life. Many found this life, and seemingly unlimited opportunities, on the Western frontier.