Despite persistent rain in the Pacific Northwest, fire has figured prominently in the history of the region. Fire was once a natural part of the environment, and Indigenous people used it in their quest for survival. But non-Native settlers and their descendants regarded fire as the enemy of the region's bountiful forests, which provided jobs for many and fortunes for some. Following devastating forest fires in 1902 (the Yacolt Burn in Washington) and 1910 (the Big Burn in Idaho and Montana), the U.S. Forest Service made fire suppression its primary mission. Federal and state fire-suppression policies came with their own problems, however, and fires have continued to ravage the state's forests. Washington's biggest fire, the Carlton Complex blaze in 2014, consumed 256,108 acres.

Indigenous Fire, ca. 1800

Oral tradition holds that Native Americans set a forest fire in about the year 1800 that consumed as many as 250,000 acres in the area between Mount Rainier, Mount St. Helens, and present-day Centralia. The fire may have been started by the Cowlitz Tribe against the Nisqually Tribe, or its purpose may have been to bring rain during a year of drought.

Forest fires in the region became increasingly common in the nineteenth century, "caused by lightning ... or coal-burning steam engines and campfires ... There was no real fire-fighting capacity, and fires tended to burn until the fall rains put them out. Mark Twain's only visit to Puget Sound, in 1895, was marred by fire smoke so thick he never saw the scenery" (Berger).

Yacolt Burn, 1902

The twentieth century began with the infamous Yacolt Burn, then the largest recorded forest fire in Washington history. It destroyed 238,920 acres – more than 370 square miles – and killed 38 people in Clark, Cowlitz, and Skamania counties. Unusual dry winds from the east fanned the fire, which traveled 36 miles in 36 hours and consumed $30 million in timber – more than $1 billion in 2023 dollars. As many as 80 other fires around the state that summer burned an additional 400,000 acres of timber. The cause of the Yacolt Burn was never determined, and there was no organized effort to stop it. Firefighting would remain haphazard for several more years.

"Only with the so-called Big Burn of 1910 – what Seattle author Tim Egan called an "apocalyptic conflagration" that vaporized 3 million acres of Montana, Idaho, and Washington in 36 hours – did the scale of a fire demand attention and resistance, as well as a more proactive effort to protect harvestable timber, and therefore dollars, from going up in smoke. The U.S. Forest Service was put to the task of preserving our natural resources, its leaders' attitudes toward fire deeply influenced by the Big Burn, which killed at least 85 people" (Berger).

The Big Burn, 1910

The summer of 1910 was abnormally dry in the West. Forest Service crews of temporary workers – and employees detailed by railroads, timber companies, and mining companies with private holdings – fought scores of fires in Idaho and Montana (touching into Washington north of Spokane), but fire suppression was complicated by poor communications, roads, and equipment, and not enough personnel. On August 20, hurricane-force winds (more than 75 mph) rose to spread the fires, known collectively as the Big Burn, and crews were helpless to stop them. Trapped men fled their camps, and many found safety by immersing themselves in creeks with their heads covered by coats and blankets. One crew hid in a mine tunnel, but five suffocated because the fire consumed all the oxygen. Homesteads, sawmills, and railroad structures were destroyed. Of the 85 confirmed dead, 75 died fighting the blaze.

Even though 1,200 to 1,500 men had been hired as firefighters, Forest Service managers asked President William Howard Taft for help from the U.S. Army. African American soldiers from the 25th Infantry Regiment at Fort George Wright in Spokane pitched in to help. The loss in timber was estimated at 3 million acres, more than 10 times the amount lost in the Yacolt Burn and larger than any other burns in recorded U.S. history. By comparison, commercial logging in Washington was felling approximately 100,000 acres of timber a year in the early 1900s.

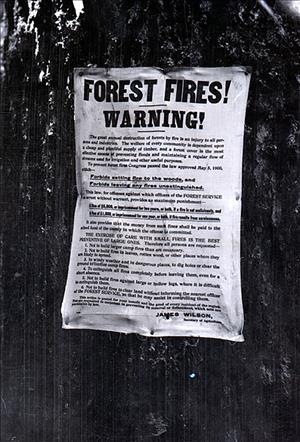

The Big Burn would serve as a turning point in national fire policy. The Forest Service began to aggressively suppress fires with full-time, trained crews, a network of fire lookouts, and campaigns to prevent fires. In Washington, this policy fit with programs started by the state and by private timberland owners through the Washington Forest Fire Association (now the Washington Forest Protection Association). Still, forest fires continued to burn in the twentieth century. Among the most notable:

The Great Forks Fire, 1951

On September 20, 1951, a forest fire burned 33,000 acres and 32 buildings in Forks, on the Olympic Peninsula, as well as several lumber mills in the area. More than 1,000 residents were evacuated as 500 firefighters managed to keep the flames from the rest of town. The summer had been exceptionally dry, and hydroelectric utilities had curtailed service to industrial users because of low water behind dams. In September, many seasonal firefighters returned to school, leaving crews short-handed. A fire thought to have been extinguished sprang to life 19 miles northeast of Forks, and east winds drove the flames toward the town. Refugees were sheltered at the Naval Station at Quillayute and at the Coast Guard Station in Port Angeles. The occurrence of such a fire in the area was unusual – the annual rainfall in Forks was 115 inches.

Entiat Burn, 1970

On August 23, 1970, lightning ignited more than 200 separate fires in the Wenatchee National Forest that consumed 122,000 acres. The fires, known collectively as the Entiat Burn, raged for 15 days, merging into five fires named Gold Ridge, Entiat, Mitchell Creek, Shady Pass, and Slide Ridge. The Forest Service used 8,500 firefighters to contain them -- though it was rain that finally put them out. Fighting the fire cost $13 million.

In the rubble of the Entiat Burn, biologists found evidence in tree growth rings of a large fire in about 1790 and one in about 1830. Foresters concluded that aggressive fire-suppression and prevention programs resulted in a buildup of underbrush and smaller trees that might have been reduced had natural fires run their course. "Everything was just dead. No trees. No birds. No fish ... Nothing. I didn't want to come back,” one farmer told The Seattle Times. In 1971, the Forest Service began a program of reforestation of the burned area.

Spokane Firestorm, 1991

While it was primarily a grass fire and not a forest fire, the Spokane Firestorm would strongly influence how the State of Washington responded to major fires after 1991.

On the morning of October 16, 1991, gale-force winds gusting to 62 mph uprooted trees and downed power lines in the Spokane area. The energized wires ignited dry grass and brush. The first alarm was received at 8:45 a.m. near Spokane International Airport, and within three hours, every firefighting resource in Spokane County was committed to battling a total of 92 separate fires that came to be called the Spokane Firestorm. One firefighter died in a machinery accident and 114 homes were destroyed as firefighters had to decide which structures to save and which to leave to the flames. Some residents were evacuated ahead of the fires; many more rushed to remove dry brush and leaves from around homes built near wildlands.

By noon on October 19, Spokane and its population of approximately 350,000 were surrounded on three sides by fires. Spokane County Commissioners and the Spokane City Council declared a state of emergency. Many of the fires were contained by October 20, but on October 21, a second windstorm struck the area with gusts to 52 mph and the contained fires flared anew. By 4 p.m., more than 4,000 firefighters called in from around Washington and Idaho managed to control the fires again.

The fires continued to burn for six days, until they were contained and fire units began to demobilize. An investigation found that utility wires caused most of the fires, but that the utility companies were negligent in only eight cases. The same week as the Spokane Firestorm, a grass fire in Oakland, California, destroyed 2,900 structures and killed 25 people, further demonstrating the hazards of urban encroachment on wildlands.

In 1992, the Washington State Legislature passed a law expanding the mobilization of resources, including the National Guard, during large fires. The law also provided for reimbursements to agencies called in to assist in large fires, and for agencies whose own resources were exhausted.

Tyee Creek Fire, 1994

On July 24, 1994, lightning ignited a fire in the Wenatchee National Forest at Tyee Creek that burned for 33 days and destroyed 35 homes and cabins. Many more structures were saved by the efforts of firefighters and by the fire-prevention strategies of homeowners. Other fires in the region on Hatchery Creek and Rat Creek consumed 40,000 acres. More than 2,775 firefighters worked on the fire lines and approximately 1,000 Marines from Camp Pendleton, California, joined the effort.

The area along Tyee Creek, 60 miles north of Wenatchee, had originally been covered with ponderosa pine, which has a thick bark and is resistant to fire. Periodic fire was essential to the tree's life cycle, and also burned off smaller vegetation on the forest floor. Over time the pine was harvested and Douglas fir, less resistant to fire, grew in its place. Meanwhile, fire-suppression policies of the Forest Service, the State of Washington, and private timberland owners resulted in a buildup of small trees and brush, providing kindling for fast-moving forest fires.

The deaths of 34 firefighters across the nation in 1994 and the fires around Wenatchee provided another opportunity for proponents of new forestry practices to question the Forest Service's tradition of aggressive fire suppression. In 1995, the federal agencies responsible for wildfire policies – the Forest Service, the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the Fish and Wildlife Service – developed the National Fire Plan. Under this program, local land managers developed fire-management plans that included "prescribed" burning (planned, controlled burns of brush and other buildup of fuel), removing vegetation, and small- and large-scale suppression.

Thirtymile Fire, 2001

On July 10, 2001, four Forest Service firefighters died while battling the Thirtymile Fire in Okanogan County. Six other persons were injured, including two hikers. It was the second deadliest fire in Washington history.

The blaze was ignited by a camper's fire 30 miles north of Winthrop in the Chewuch River Valley in the Okanogan National Forest. The blaze had grown to just 25 acres in size when 21 Forest Service firefighters were dispatched to contain it. After the crew arrived, the fire blew up and surrounded them. The firefighters deployed their safety shelters, but four died. One firefighter sheltered himself and two hikers in a safety shelter designed for one person. Some crewmembers found refuge in the water of a creek. The fire grew to 9,300 acres before it was brought under control.

There were no towns or structures near the fire. Under Forest Service policy, managers were obligated to fight the fire because it was started by human activity. Naturally occurring fires, such as those started by lightning, were allowed to burn. Had the fire started one mile to the west, in a designated wilderness area, regardless of origin, it might have been allowed to burn because of the fire management plan in place for wilderness areas.

Killed were Tom Craven, 30, of Ellensburg; Karen FitzPatrick, 18, of Yakima; Devin Weaver, 21, of Yakima; and Jessica Johnson, 19, of Yakima. An investigation faulted 11 Forest Service employees who had violated safety rules and disregarded signs of danger. This incident, and the deaths of 14 firefighters in Colorado in 1994, caused a rethinking of Forest Service firefighting policies.

Carlton Complex Fire, 2014

More than 111 years after the Yacolt Burn, the Carlton Complex Fire in Okanogan County surpassed it as the largest wildfire in acreage consumed (256,108) in Washington's recorded history. Ignited by lightning on July 17, 2014, the blaze destroyed 111 homes in and around Pateros, located on the Columbia River. Earlier in the day, the sheriff began evacuating the entire town of 667 residents, in some cases threatening laggards with arrest. The evacuation was a success, and when the fire raced in a little after 8 p.m., no one was killed or injured. Residents sheltered at an evacuation center in Chelan and returned the next day to scenes of devastation, although the main business district was spared.

Okanogan Complex Fire, 2015

On August 14, 2015, lightning storms ignited the Okanogan Complex fires, which soon grew into some of the biggest in the state's worst-ever wildfire year. They began with several separate fires in the timber and grasslands above Omak and Conconully in Okanogan County. Within three days, large fires were raging on both sides of the Okanogan River. At one point, the fire burned all the way into Omak before being beaten back by firefighters. On August 20, another fire broke out near Twisp and three firefighters died in a crash as they attempt to escape the flames. When the smoke cleared in the fall, the Okanogan Complex and the related Tunk Block fire constituted two of the biggest fires in what had become the worst wildfire season in state history.