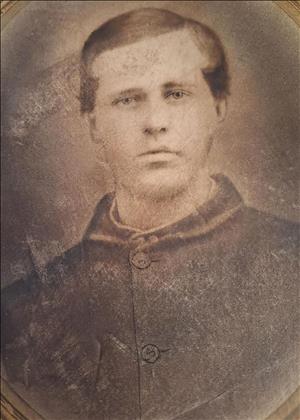

Eldridge Morse contributed to the growth of pioneer Snohomish County in myriad ways. Arriving in Washington Territory just after the Civil War, the Connecticut native settled in the riverside town of Snohomish, where he worked as a lawyer, farmer, newspaper publisher, civic organizer, politician, librarian, journalist, and businessman from 1872 until his death in 1914 at age 67. He is perhaps best remembered as the owner and operator of The Northern Star, the first newspaper in Snohomish County.

From Connecticut

In his unpublished memoir, written in September 1892, Eldridge Morse (1847-1914) writes: "I was born in Wallingford, New Haven County, Connecticut, on April 14, 1847; I was 14 years old the day Fort Sumpter fell. Abraham Lincoln was shot on my nineteenth birthday. I first came to California in 1867. Five years thereafter to a day, I again entered the Golden State on my way to Puget Sound. I have resided in Snohomish County since the 1st of November 1872” (Morse).

His father was Eldridge Morse Sr. (1809-1870). At 19 years of age, in 1830, "my father’s first venture was selling brooms for Uncle Elkanah ... He traveled all over Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Wisconsin, Michigan and the lakes before settling down to business at Detroit" (Morse). His father returned penniless but "richer by numberless experiences and adventures," to use Morse’s words. By the time Eldridge Jr. was born in 1847, Eldridge Sr. had a farm with a nursery and fruit business. "As a child my work was tending to fruit, care of cows and market gardening" (Morse). Besides being a great general reader, his father had an endless stock of anecdotes and stories, personal reminiscences, and adventures to relate. Writes Morse:

"There was no important place, anywhere in the United States, of my younger days but what my father or his brothers had been there. Therefore, whatever talent I may possess for getting over a difficult country, noting and describing its interest and resources, was literally born in me, inherited, then trained by all those stories childhood loves so dearly to hear, and treasures so fondly.

"My mother [Angeline Amanda Smith (1816-1899)] is still alive ... from my earliest recollection mother was an invalid, for years confined to a sick bed and supposed to be liable to die at any time. She is now 75 years old and has comparatively good health for one of her years. She was the mother of nine children – six boys and three girls – but three of the boys died when very young" (Morse).

The Civil War

Writes Morse: "Finally in February 1863, I determined to go for a soldier. My mother gave a reluctant consent." He enlisted for three years in New York City and was mustered on Bedloe’s Island, now the location of the Statute of Liberty. He was sent to Fortress Monroe, which is today a National Monument, and then to Richmond, Virginia. "The war was practically over. Grant's victorious army was coming into Richmond from Burkesville station. Hundreds of recently paroled confederates lined the streets" (Morse).

Morse served for more than two years at Willets Point, New York harbor. In September 1867, he was sent by way of the isthmus of Panama to San Francisco. "I served five months at the Golden Gate [Fort Point] and nearly two months on Yerba Buena Island, in the harbor between San Francisco and Oakland. My army service was mostly pleasant and profitable, my expenses nominal, with chances to earn money outside of regular pay. I was able to save a total of $1500, from every source, in three years’ service" (Morse).

Morse was undecided whether to re-enlist for three years and save up for collegiate training in the classics and sciences, or go to Virginia City, a mining boomtown, for the high wages being paid there, where he could build up the collegiate nest egg in less time. "At my mother’s earnest request I gave up both of these projects, and on my discharge, went directly east to New York, via the Nicaragua route. I reached home to find that the old place, which had never been out of the Morse family name since 1638, had been sold only three days before. I felt fooled and stayed at home only a few days" (Morse).

Educated in the Law

The late Noel Bourasaw wrote in his Sagit River Journal blog, "We have found no record that he ever returned [to Connecticut], even when his father died in 1870. His mother was a widow for more than two decades. He soon moved to Albia, Iowa, to join his elder, unnamed sister" (Bourasaw). Writing later about these years, Morse explained:

"There I became a book[ing] agent, school teacher and law student. In April 1869, I was admitted to practice law at Albia, Iowa. In the fall of 1870 I entered senior class of the law department, University of Michigan, and graduated the follow[ing] spring. I was also admitted to the United States district and circuit court at Detroit, and the Michigan state court at Ann Arbor. I returned to Albia and went into law practice. The money I saved in the army gave me my law education, bought me a law library and started me in practice.”

"In April 1871, I married my first wife [Martha A. Turner, 1851-1876] at Albia, and my eldest son Ed C. Morse was born there in April 1872. I left Albia about September 1, 1872, for the Pacific coast, going by railroad to San Francisco" (Morse).

Arriving in Snohomish

Morse, who arrived in the recently platted Snohomish City in 1872, describes his journey and first impressions in his memoir:

“The bark [three-masted sailing vessel] Tidal Wave, Captain Reynolds, brought myself and family to Port Madison. From Port Madison I went to Seattle on the steamer Ruby. There Hon. E. C. Ferguson induced me to go to Snohomish, then a center for logging camp men and a frontier trading post. There were many single men, but only three families there. Soon I was busy practicing law, farming, gardening, organizing various literary and public societies, and doing much work connected with the various county offices” (Morse)

Before long, Morse began organizing a society for the study of history and science. A fellow newcomer, Dr. Albert Chase Folsom (1827-1855), joined him in the endeavor. Folsom, a former army surgeon with experience in the Civil War, arrived with a scientific collection of more than 100 fossils, gems, and bones, and no wife, who was left back in Wisconsin. It's easy to imagine the mutual attraction of the two newcomers, the young lawyer, Morse was 25 years old, and the older doctor, who was 45 – the first professional men of law and medicine to hang their shingles in the town sited on the north bank of the Snohomish River.

The notion of the Snohomish Atheneum as a library and museum developed in 1873. Snohomish pioneer Emory C. Ferguson (1833-1911), a carpenter by training, had been instrumental in the founding of the Steilacoom Library Association, established by a special act of the territorial legislature in 1858. Consequently, Ferguson accepted the position of president of the new Snohomish Atheneum. Folson became corresponding secretary, and Morse the librarian. The lifetime membership fee was $25, and 300 books were donated from the membership. “Within three years the library had grown to more than 600 volumes, containing the largest and best selection of scientific works to be found in the territory” (Hunt and Kayor).

The Athenea Papers

A collection of handwritten journals, bound with hand-stitched thread, was discovered in 1983 in the Special Collections of the University of Washington Library by Stuart Grover, a student employee. Grover wrote an article for the journal Portage titled "Pioneer Snohomish City, An Intimate Look (1874-75)." He begins by noting the active minds of early Snohomish residents and how a core of perhaps a dozen men filled the political, commercial, agricultural, social, and cultural positions, many holding multiple posts. He noted that Morse, for example, served as Deputy Auditor of the County Commission, co-President of the Free Religious Association, and Secretary of the Agricultural Society and the Telegraph Company.

The inaugural handwritten journal was called The Shilalah, which announced itself as, “A Live New Paper, devoted to Art, Science, Literature, and General News, regularly appearing now and then, designed to promote harmony, sociability, good nature, and good behavior” (Grover). It was put together by Morse and Folsom and carried this statement of purpose: “We must have in this community some kind of intellectual culture or else the brute instinct inherent in man will predominate, will asset its superiority and become the ruling passion in spite of previous associations and training” (Grover).

The name of the journal changed to the Athenea when Snohomish women took over the writing and editing. Grover writes, “If the men had come looking for a new life, the women also carried hope into the unsettled wilderness.” Discussions around the nature of marriage presented a picture of couples bound in matrimony but relying on the goodwill and common sense of each other for survival. In the frontier town, women taught, worked in stores, tended bars, and kept the books for businesses, making the women indispensable and irreplaceable. “Frontier women, uncorseted, contributed to all aspects of community activities” (Grover).

Few Native Americans are recorded in the journals, but a potlatch attended by white residents is described in an 1874 issue of the Athenea: “Grand preparations for refreshments of all kinds, with roast dog, fried hump-backs, seasoned with kelp and clover, with clams on the half-shell and grasshoppers for side dishes. For drinkables, shark and dog-fish oil, ad libitum. Pine cones, fir balsam, and skunk cabbage for dessert.”

The Athenea was published twice a month over the next two years. Issues were read aloud when the group gathered for meetings of the Atheneum – “to fuel their flight from insularity,” Grover speculates.

With the association's growth came the desire for a building devoted exclusively to the interest of the society. On June 5, 1876, the cornerstone of a building located on the northeast corner of First Street and Avenue D was laid with appropriate ceremonies. “Around me are many familiar faces of brave, true-hearted pioneers, who, a few years ago found this valley a wilderness, uninhabited by civilized beings,” Morse told the gathered members and onlookers, according to the publication of his address at the laying of the cornerstone in Morse's own newspaper, The Northern Star, the following Saturday, June 15, 1876. It was to be a two-story building, 100 feet long, maybe the largest in the Territory.

The Northern Star (1876-1879)

Snohomish historian William Whitfield documented the establishment of The Northern Star newspaper in his book History of Snohomish County, published in 1926. Writing about Morse, he notes: “He had not at first intended starting a paper at Snohomish, but for nearly a year had tried to get someone else to do so – but failing in this, he went to Olympia and brought the old plant of the defunct Olympia Farmer of R. H. Hewitt, shipping it to Snohomish on the steamer Zephyr” (Whitfield, 789).

In her history of early Snohomish County newspapers, Margaret Riddle writes that Morse purchased a Washington Hand Press and taught himself how to set type. His inaugural issue is dated January 15, 1876. Under a "Local Items" headline we’re treated to the afterglow of the recent Christmas celebrations.

“On the evening of the 23d nearly every resident of the place, with their families, turned out to the hall to receive their gifts from the Christmas tree. Ample provisions had been made by the managers, so that nearly every one was duly remembered. Some of the gifts were superb. It was estimated that $600.00 was distributed from the tree during the evening. On the afternoon of the 24th over thirty of our citizens went to Lowell to the ball on Christmas Eve. The hall was tastefully hung with evergreens and otherwise decorated with appropriate mottoes. The music was perfect and the ball did not break up till four o’clock in the morning, which indicates better than anything else that perfect harmony and good feeling prevailed during the entire night. The river was remarkably high, and as many coming from a distance had to pull against the current, either in coming or going. There was no ball here, but we are informed the young folks intend having one on New Years Eve. We wish them a good time” ("Local Items," January 15, 1876).

In the issue dated March 11, 1876, Morse announces the death of his wife, who had been bedridden with an unknown illness. Martha Morse (1851-1876) died on March 10, 1876. While his account of Martha in his memoir is short, Morse makes up for it in her obituary published March 18 in The Northern Star: “In the summer of 1869 and winter of 1870 and 1871, Mrs. Morse was engaged in teaching, meeting with marked success; her knowledge of history, familiarity with poetry and taste for the sciences, rendering her an accomplished instructor as well as agreeable companion." He continues:

“At her last birthday, her husband presented her with a beautiful dress. She spent all, or nearly all her leisure time when well enough to do so, in making and ornamenting this dress. When her last hours approached she told her husband she had no requests to make except she wished to breathe her last in his arms, and to be buried in that dress– a dress she never wore, on which she had spent so much time, forming and ornamenting a shroud that was to clothe her loved form in death. Her little boy, to whom she was fondly attached, she consigned to her husband and sister’s care, without a word of direction or expression of doubt but that her little orphan would be fondly cared for when its mother rested in the grave with flowers and grass growing above her” (The Northern Star, March 18, 1876).

On September 16, 1876, Morse made a plea in The Northern Star to hold a county fair after a one-year hiatus. Two years earlier an impromptu citizens’ fair had been held on only a few weeks notice in E. C. Ferguson's Blue Eagle building in Snohomish, which had served as the county courthouse since it was built as a saloon in 1864. Morse proposed that, "Farmers from all parts of the county should come together, bring a fair sample of whatever they have, shake hands, form each other's acquaintance, exchange ideas, and not get miffed because somebody has a bigger pumpkin, a fatter calf, or a faster horse than all others" ("Our County Fair"). He added: "Farmers of Snohomish county, this is no traveling show, no Punch and Judy affair. Your individual honor is at stake. You have the means of making this exhibition an honor to the county" ("Our County Fair").

The Snohomish County Agricultural Society held four fairs, and at the close of each, the best exhibits represented the county in the Territorial Fair in Olympia, where they "took first prize for the best display of fruits and vegetables of any county in the whole Territory of Washington" (Blake). In 1878, the society had less than $150 in debt on its 40-acre Fair Ground Addition to Snohomish when it sold the property during a financial panic and stopped holding fairs. The first Snohomish fairs planted the seed of what today is the Evergreen State Fair, held in Monroe since 1949.

Married Again, Briefly

Historian Noel Bourasaw, who fleshed out Morse’s bare-bones memoir, writes: “Living and working in a frontier town with a small son must have been quite a challenge. Within a year after [Martha's] death, Morse married again, in 1877, this time to Fannie Oliver. We find her name along with Dr. Folsom's as associate editors on the masthead of The Northern Star in the spring of 1877” (Bourasaw). On November 2, 1877, Fannie gave birth to a son named Melvin Oliver, but the name never appears again until it was tracked down by Ann Touhy with the Snohomish Historical Society. Touhy learned that after Eldridge and Fannie ended their short marriage, she took the boy to the home of her parents in Centerville (now Stanwood). “They were still there for the June 1880 census along with Fannie's sister, who was also divorced, and the boy's name was listed as Melvin Morse” (Bourasaw).

"The Only Historian of Snohomish County"

Reviews of the “Morse and Folsom newspaper” by historians over the years are raves all around. “It was away ahead of its time and for three years its publisher tramped through the dense forest, swam the streams and camped out in the rain wherever night overtook him in an effort to make it a self-supporting enterprise,” wrote Hunt and Kaylor in 1917. The 1906 volume The Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties reminds readers that the newspaper started in a village that had been founded up against a dense forest where stumps were still standing in the streets. "The paper began to make its appearance which, for literary excellence, variety of subjects treated and general ability might safely challenge comparison with the best and brightest weekly papers of the present time" (The Illustrated History ...).

William Whitfield published Morse’s entire Centennial History of Snohomish County, Washington Territory in the first volume of his History of Snohomish County, just as it was published in The Northern Star on July 8, 1876. Whitfield wrote, “it should be preserved in this volume intact, as written by Eldridge Morse, the first, and for many years thereafter, the only historian of Snohomish County.” Morse also read the history at a Centennial Celebration on July 4, 1876.

The following year, the local logging industry went into a depression, and subscriptions to the paper dropped by half. The town’s wealth depended on the price of a log when it was pulled from the river. In many ways, Snohomish was little more than a logging camp. The final issue of The Northern Star was published on May 3, 1879.

Folsom's Demise

Three years after The Northern Star folded, the first issue of the Snohomish Eye appeared on January 11, 1882. Morse became one of its contributors, even writing the obituary for his friend and business partner, Folsom, in the May 28, 1885 issue. Several months earlier, the paper had reported that Folsom had been removed by friends to the Exchange Hotel, where he died on May 11. Folsom’s view from his sick bay may have been of the Atheneum building across the street. If so, it was the view of a majestic building with a sad story. The society had to foreclose on the unfinished building in 1877, only two years after its dedication, and it was purchased by Isaac Cathcart (1845-1909), owner of the Exchange Hotel.

In his obituary of Folsom, Morse told of Folsom’s educational background and how he interrupted his enrollment in the Classics Department at Harvard University to travel with his botany professor to study in South America. Earning a degree in Classics upon his return, Folsom immediately entered medical school to earn a second degree from Harvard. He was commissioned as a second assistant surgeon in the U.S. Infantry in 1848, and assigned to serve under Robert E. Lee, the beginning of a long stretch of military service that included an assignment with the Secret Service in Costa Rica. His first wife had died many years earlier, and upon resigning his military commission, he married a Wisconsin woman, but it was a union that “proved very unfortunate,” Morse writes. It seems that the first medical doctor of Snohomish County arrived with a broken heart and no ambition to “accumulate property or secure a place or position for himself” – he offered his medical services for voluntary payment. “When he first came to Snohomish City [he] was a man of remarkably fine personal appearance. For some years past it had been a source of sorrow to his friends to see his form become bent and see him decline in health and strength of body and mind. His last sickness was long and painful, and when death came, it was welcomed by his friends as a real relief from his sufferings” ("Life of Dr. A. C. Folsom").

A Home on the River

Returning to Morse's 1892 memoir, we read:

“My present wife [Alice Mathews 1858-1900] I married in 1885. Since 1885 I have traveled but little. The most I have written since then has appeared in the Snohomish Eye, the Tacoma Ledger and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Since 1875, I have traveled fully 70,000 miles in the state of Washington afoot or in an open boat, gathering information. I have, perhaps, 70,000 pages of manuscript thus gathered. Less than 10 percent of the information in possession has ever been in print. In 1885 I dropped almost everything else for farming and market gardening. I now have 150 acres, mostly choice river bottom land which I am fitting for a dairy ranch the raising of fruit and vegetables. My home is on [the] Snohomish river, some three or four miles south of Snohomish City ... I did not desire law practice. I [am] determined on farming and gardening, with study or recreation, my first work being to master such knowledge as would fit me for studying the Encyclopedia Britannica" (Morse).

Morse did go on to read the Britannica twice, it’s written, and if true it makes the ending of his memoir an even more intriguing puzzle. Morse tells of his acquiring the mystical name S’Be-ow from the local Native people because he would remove his dentures, implying that he could take himself apart and put himself back together. His final words, following a long story of an adventure with two Natives: “Nothing could shake their belief that I was the genuine, original S’Be-ow, with full power of performing miracles and putting myself through countless transforms and no fraud or sham” (Morse, September 28, 1892).

Death of a Dream

In a two-part series of articles in the Snohomish County Tribune, published on May 27 and June 17, 1910, Morse details the history of the Atheneum Building. “In 1875, the Atheneum was in excellent condition, no debts and considerable sums of money in the treasury,” Morse begins. His friends and partners in the endeavor, Dr. Folsom and W. H. Ward, wanted to build a large building with a stage for performing entertainment to raise money. "My suggestion to enlarge the collection instead was voted down," Morse writes. Construction began in June 1876, and a year later the exterior of the structure was complete, but the panic of 1877 stopped work. Ferguson donated the lumber to build a stage on the second floor so Folsom and Ward could begin producing their fundraising shows. The shows were excellent, writes Morse, but with only “trifling net results.”

Morse ends the history by giving Cathcart credit for “his fine finish” of the structure, guessing he spent $15,000, though wasted as an investment, Morse felt. Throughout the nineteenth century, the structure was referred to as either the Cathcart Opera House or the Atheneum in the newspaper, depending on the activity. Over the years, Cathcart made and lost a fortune and ended up offering his empty opera house to the town’s first militia for drills until their own Amory was ready. The cultural landmark of early Snohomish was listed as vacant on Sanborn Insurance maps just before it was dismantled for scrap in 1910. “The history of the building is a history of the failure of the Atheneum as a society or public institution” (Morse).

At the time of his death in 1914, Morse had a farm near Snohomish and a house in town. Edward C. Morse (1872-1936), his eldest son by his first wife, was a mining engineer at Republic, Washington. Morse was also survived by five children with his third wife, a daughter Belle Matthews of Markham, Ontario; John in Seattle; and Arthur, Harley, and Roland, all living in Snohomish.

Eldridge Morse was honored at his funeral by Post 10 of the Grand Army of the Republic, which he had helped found. He is laid to rest under a marker listing him as a veteran of the Civil War in the GAR Cemetery of Snohomish.