From 1884 until mid-1887, the Northern Pacific ran a train from Tacoma to Seattle. When the train began to operate on June 17, 1884, Seattleites were ecstatic. Henry Villard (1835-1900) had acquired the transcontinental railroad, and Seattle had hopes of becoming its terminus. But Villard quickly went bust, and pro-Tacoma, anti-Seattle interests acquired the Northern Pacific. The line between Tacoma and Seattle was called the Orphan Road because of its gross neglect and poor service. Not until 1887 did Seattle become the true terminus of the Northern Pacific's transcontinental route.

Henry Villard

In 1873, the Northern Pacific announced that Tacoma would be the Puget Sound terminus. It appeared that there would be no service to Seattle. Until February 1881, the hope of any Seattle connection to the uncompleted transcontinental Northern Pacific railroad line looked bleak.

In early 1881, this changed. In October 1880, Henry Villard (1835-1900), who controlled railroad and steamship companies along the Columbia River and the Willamette Valley that served Portland, Oregon, extended his empire to Puget Sound. Heading the recently incorporated Oregon Improvement Company, Villard purchased both the Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad and the coalmine at Newcastle for $750,000. The Oregon Improvement Company was formed to operate railroads, steamboats, ferries, warehouses, wharves, locks, mines, and flumes, in effect a monopoly over Washington and Oregon.

Villard’s empire soon grew beyond the Pacific Northwest. In February 1881, he and an investment group he organized spent more than $36 million on Northern Pacific Railroad stock. By the end of the month he controlled 60 percent of the railroad’s stock and would shortly take over as president of the Northern Pacific. Seattle businessmen and King County residents felt ecstatic. Because Villard was so heavily invested in King County, they believed that a Seattle transcontinental railroad connection was assured. Indeed, in October 1881, Villard visited Seattle and declared that "within twelve months of today, an unbroken railroad from St. Paul to Tacoma to Seattle" would be running (Armbruster, 68). He said the Northern Pacific railroad would build railroad tracks from Tacoma to Stuck Junction (later renamed Auburn), where the line would veer east to cross the Cascade Mountains.

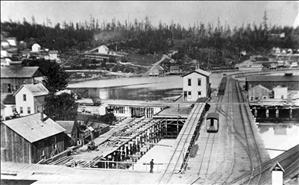

On August 15, 1882, the Puget Sound Railroad Company, incorporated by C. H. Prescott, J. H. Dolph, John W. Sprague, and R. N. Armstrong, was formed to construct railroad line from Renton to Stuck Junction, the connection point to the Northern Pacific. They also improved the former Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad line from Renton to Seattle, including construction of a trestle that carried the tracks from downtown Seattle around Jackson Street to near the mouth of the Duwamish River across the Elliott Bay mudflats.

Chinese Laborers Lay the Tracks

By autumn 1883, the construction crew had 1,400 Chinese laborers working on the line. On October 18, 1883, a Seattle Post-Intelligencer article stated, "Laborers swarm through the fields like bees and the grading and leveling give one the impression that the whole face of nature is being torn up." A Post-Intelligencer, reporter observed leaving Seattle a construction crew and a steam engine towing 14 cars including:

"... two flat cars of ties, two flats with a pile driver, two carrying squared timbers, one with flooring, one with old wheelbarrows, one with new wheelbarrows and carts, one with scrapers and picks, one bearing Chinese laborers, one boxcar filled and miscellaneous merchandise, one passenger car, and one caboose filled with people and their belongings" (Armbruster, 85).

It appeared that a Tacoma-Seattle connection would be completed within weeks. The fall 1881 headline -- Seattle’s Future Assured! -- that announced Villard’s investment in King County appeared to be coming true.

Villard's Bad Day

But Villard's fortune had already begun to turn. He hosted the September 8, 1883, last spike ceremony in Montana, honoring the completion of the transcontinental Northern Pacific railroad from the Midwest to Tacoma and a week later arrived in Seattle to a grand reception. As Villard stepped onto the city docks to be received by Seattle dignitaries, he was given a handful of urgent telegrams from the East. A reporter watching Villard reading the telegrams described his demeanor:

"It seemed to me that he was turned into a marble statue. I shall never forget the terrible look of agony on his face" (Armbruster, 80).

Unknown to the reporter and to King County citizens, the telegrams announced that Villard's Western companies were in trouble. The stocks of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Oregon Improvement Company, and his other Northwest holdings were plummeting. The cost of completing the transcontinental line was $14 million over budget and he had overspent in other areas of his empire building. His companies were in the red and his empire was shattering. Villard shortened his Seattle visit and rushed back East to stop the hemorrhaging. By year's end he gave up trying to save even a portion of his companies. In January 1884, he resigned as Northern Pacific President.

Back to the Drawing Board

The officers who assumed control of the railroad company had limited funds and no financial interest in the Oregon Improvement Company and its Newcastle coal mines. They saw a railroad connection to Seattle as competition with Tacoma, a town in which the Northern Pacific had substantial property holdings and financial interest. At about the time of Villard’s resignation, construction stopped on the Seattle-Tacoma line. The final three miles from Titusville (renamed Kent) and Black River Junction (near Renton) was left uncompleted. And King County wondered if the line would ever be finished.

But after the winter storms passed, the railroad completed the connection to Seattle. The Northern Pacific's motivation was obvious. When the United States Congress chartered the Union Pacific Railroad in 1862, it granted the company 10 square miles of land for every mile of track it laid. In 1864 that law was amended, raising the land grant to 20 square miles for each mile of track. On the same day, Congress chartered the Northern Pacific Railroad and also granted it 20 square miles of land for each mile of completed track. By extending its line to Seattle, the Northern Pacific hoped to gain ownership of hundreds of thousands of acres of land located "chiefly in King County" (Prosch, 310), land it could later sell.

Maximum Inconvenience, Minimum Amenity

On June 17, 1884, at 2:45 p.m. the first train steamed into Seattle from Tacoma. The train was greeted in Seattle by a 21-gun salute made with a canon left over from the 1856 Indian War.

This was good, but the railroad, due to its meager construction budget, had a number of faults. The tracks lacked ballast, making the train ride a bumpy one. The line did not extend to the Seattle docks. No sidetracks were built to hold railcars so they could be loaded and unloaded. There was no way to turn a steam engine around: Every train arriving in Seattle had to return with the steam engine backing up all the way to Tacoma. And once in Tacoma, all passengers and freight had to transfer to the Northern Pacific transcontinental train.

Two and one half weeks after the first train reached Seattle, the Northern Pacific started running the three-hour, 25-mile trip from Tacoma. Five days later, on July 10, 1884, the first timetable was issued. The schedule was devised to cause maximum inconvenience for Seattle travelers. Passengers traveling to Seattle on the transcontinental Northern Pacific line had to stay overnight in Tacoma. Travelers arrived in Tacoma after midnight and had to stay overnight and nearly all of the following day before the Northern Pacific departed Tacoma at 10:15 p.m.

Travelers leaving Seattle for the transcontinental trip had the same layover. The train remained in Seattle for about 12 hours, left Seattle at 1:50 p.m. and backed up to Tacoma. Passengers were then obliged to stay overnight in Tacoma while waiting for the transcontinental train to depart.

From Poor Service to No Service

Seattle howled about the poor service and the Northern Pacific responded on August 22, 1884, by terminating its train service to King County. For the next 14 months the Northern Pacific refused to operate trains over the line. The Seattle/Tacoma line became known as the "Orphan Road," a railroad line unwanted and unused.

The only leverage that Seattle and King County farmers had was the 1864 Land Grant Act. On September 26, 1885, King County businessmen and farmers held a mass meeting at Titusville (Kent). The citizens demanded that the railroad service restart over the line or they would lobby the U.S. Congress to revoke the Northern Pacific land grant to King County land. The Northern Pacific, realizing that sentiment in Congress favored Seattle, relented.

Exactly one month after the Titusville meeting, train service restarted with two trains a day leaving Seattle: a 2:25 a.m. departure that connected to the transcontinental train and a 3:10 p.m. departure for Stuck Junction (Auburn). The Northern Pacific also constructed a turntable so that the steam engine could be turned around and could steam to Tacoma forwards instead of backwards. Train fare was $1.00 to any destination along the line. But service remained poor and would deteriorate. By mid-March 1886, the Northern Pacific changed the Seattle departure time to a 6:40 a.m. The Seattle train arrived in Tacoma two hours after the Portland and eastbound train left, causing a 15- to 22-hour layover. In September 1886, while the line’s only passenger coach was undergoing repairs, the Northern Pacific provided a pathetic boxcar with a few benches for Seattle passengers.

Tribulations Terminated

By mid-1887, at the end of the 1883 depression, the railroad line was not an orphan anymore. The Northern Pacific came to the realization that Tacoma could not supplant Seattle as the dominant city in Puget Sound, no matter what the railroad company did. James McNaught, a Northern Pacific agent based in Seattle, stated "It is a fact that one car of freight is brought to stay at Tacoma, where ten cars go to Seattle." Besides, competitors were snaking railroads to Seattle: from the North the Canadian Pacific transcontinental railroad; from the East the Great Northern railroad; and from Seattle to the East the Seattle, Lake Shore, & Eastern. Improvements were made to the Tacoma/Seattle tracks and, in the words of a Northern Pacific spokesperson, a "reasonable connection" was established.

Fourteen years after the Northern Pacific announced Tacoma (instead of Seattle) as its Puget Sound terminus, Seattle became the end of the Northern Pacific line.