On April 6, 1924, four airplanes lifted off from Seattle's Sand Point Aerodrome in a quest to be the first to fly around the world. The adventure-filled saga was closely followed by many across the globe, especially those who were on the planes' flight path. One aircraft crashed in Alaska and another sank in the Atlantic Ocean, but almost miraculously, there were no serious injuries. The airmen battled bad weather, illness, exhaustion, and mechanical problems, but after a nearly six-month journey, they prevailed. Two of the original planes returned to Seattle on September 28, joined by a replacement plane for the one that sank. The world rejoiced.

Planning the Flight

The first successful manned flight occurred in 1903, but it took World War I (1914-1918) to kick-start the development of the airplane and air travel. This accelerated after the end of the war, and perhaps inevitably, nations began competing to determine who could be the first to fly the farthest. By the early 1920s, several countries were vying to be the first to circumnavigate the globe. Great Britain tried unsuccessfully in 1922 and France the following year, and by then other countries, including the United States, were getting into the race. In the spring of 1923, the U.S. Army Air Service (a forerunner of the U.S. Air Force) began planning its own flight. The service saw that the odds of success would be higher if a small squad of planes flew instead of just one, and it decided to send a fleet of four planes aloft, each with two crewmembers. However, there was no aircraft then in existence that could make such a flight.

The Air Service considered both the Fokker T-2 Transport and the Davis-Douglas Cloudster as potential candidates, and approached Donald Douglas (1892-1981), the owner of the Davis-Douglas Aircraft Company, about the Cloudster. Douglas suggested another plane – a modified DT-2, a torpedo bomber that he had recently built for the U.S. Navy. It was a well-built and reliable aircraft that could use both wheels and pontoons for landing. Pontoons were a must for the trip, since the airmen would be flying over large parts of the world where the only place to land was on water. In August 1923, the Air Service approved the proposal.

The biggest modification necessary was to make the DT-2 capable of long-distance flights of 800 miles and more. Douglas worked with another Davis-Douglas employee, Jack Northrop (1895-1981), to make the necessary modifications. The biggest was to increase the plane's fuel capacity. All the provisions for torpedoes were removed and the fuel tanks were enlarged, which multiplied the plane's fuel capacity roughly four-fold, from 115 gallons to approximately 450 gallons. A prototype proved successful, and Douglas was subsequently awarded a contract for four more planes. The new aircraft was named the Douglas World Cruiser. The last one was delivered on March 11, 1924, only six days before the planes departed from Santa Monica, California, to Seattle for the final preparations for the round-the-world flight.

The Planes and Crews

The Douglas World Cruiser was built from Sitka spruce. The open-cockpit plane could accommodate two crewmen, and measured 36 feet, 6 inches in length, 14 feet, 7 inches in height, and had a wingspan of 50 feet. It weighed 4,299 pounds when empty but could take off with a weight up to 6,900 pounds. Equipped with a 420 hp Liberty V12 engine, the aircraft's maximum speed was 103 miles per hour, though it generally cruised between 70 and 80 mph. Its ceiling was 10,000 feet. There was no radio on the plane, no parachutes, no life preservers, and each machine was limited to carrying 300 pounds of supplies.

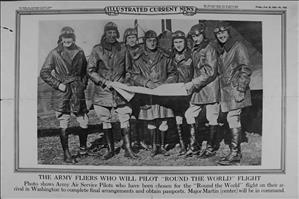

The planes were each numbered and named after one of four major cities in the U.S., and each carried a crew of two. The Seattle's pilot in plane No. 1 was Major Frederick Martin (1882-1954), the designated flight commander for the journey. He was accompanied by flight mechanic Staff Sergeant Alva Harvey (1900-1992). The pilot of the Chicago, plane No. 2, was Lieutenant Lowell Smith (1892-1945) and the co-pilot was First Lieutenant Leslie Arnold (1893-1961). The Boston's pilot in plane No. 3 was First Lieutenant Leigh Wade (1897-1991), while Staff Sergeant Henry "Hank" Ogden (1900-1986) was flight mechanic. The pilot of the New Orleans, plane No. 4, was Lieutenant Erik Nelson (1888-1970), and its co-pilot was Lieutenant John Harding Jr. (1896-1968). The team first trained at Langley Field in Virginia before traveling to the Douglas factory in Santa Monica in February 1924.

The original plan called for the flight to begin in Washington, D.C., but this was changed to make Seattle the starting point. Caches of supplies, including 35 replacement engines, other spare parts, and thousands of gallons of gasoline, were distributed at points where the flight would cross on land. On the seas, American cruisers and destroyers, as well as Coast Guard cutters, were scheduled to be placed at strategic locations at preset times as the aviators passed by to provide help if needed. Three of the four planes left Santa Monica on March 17, while the New Orleans left two days later, but they all landed at Seattle's Sand Point Aerodrome on March 20, where they were fitted with pontoons and tuned up for the upcoming journey. The team set the departure date for Wednesday, April 2, but bad weather and mechanical issues pushed this back three days. On April 5 a crowd of Seattleites gathered hopefully to watch the departure but Martin, in the Seattle, accidentally damaged his plane while preparing to take off. Though minor, the incident was enough to delay liftoff one more day.

On to Alaska

A crowd of 300 or so returned to Sand Point the next morning, Sunday, April 6, and this time they were not disappointed. Shortly after 8:30 a.m. the Seattle lifted off into cool, cloudy skies, followed by the New Orleans and, minutes later, the Chicago. Then came a pause. The Boston raced down the lake at least three times in a vain attempt to lift off, but the plane was too heavy. It returned to the staging buoy near the airfield, where pilot Wade hastily unloaded some supplies and gasoline. By this time it was passing 10 a.m. and he was more than an hour behind the other fliers. But his effort paid off and Wade soon soared into the skies, accompanied by delighted cheers from the crowd.

The planes were bound for Prince Rupert, British Columbia, a roughly 600-mile flight. The first three arrived shortly before 5 p.m., while Wade landed about half an hour later. Although the flight was without incident, the landing proved to be anything but for the Seattle. Martin had the misfortune to land in the middle of a snow squall and misjudged his altitude as he approached the waters of Seal Cove at the eastern edge of Prince Rupert. Puzzled observers watched his unusually steep angle as he descended toward the water, and he landed with such force that he broke two of the plane's struts and several brace wires. He and his crewmate quickly made repairs, and the planes departed for Sitka, Alaska, on April 10, where they remained for three days.

The flight from Sitka to Seward on April 13 provided an unexpected challenge. As they followed the shoreline along the southern coast of Alaska, the planes flew into a blizzard. Visibility dropped to the point that the pilots were forced to fly less than 100 feet above the water so they could see the shoreline and the breakers. On the hop from Seward to Chignik two days later there was a scare when the Seattle briefly went missing. Two nearby destroyers were alerted, and the plane and its crew were found safe and sound the following morning. The aircraft had been forced down by an oil leak but landed safely off Cape Igvak. It was taken to the nearby native village of Kanatak for an engine change, while the other three planes flew ahead to Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands on April 19. There they waited for the Seattle, which finally left Kanatak on April 25 and flew to Chignik, where weather delayed its departure to Dutch Harbor until April 30.

The Seattle Crash

Martin and Harvey left Chignik in the Seattle about 11 a.m. that morning and were expected in Dutch Harbor around 6 p.m. Instead, reports began coming in during the afternoon that the plane had not been seen passing any of the checkpoints along the route. As the hours went by with still no sightings reported, growing concern changed to fear. The Coast Guard cutter Algonquin, which was patrolling the route between Chignik and Dutch Harbor, radioed a request for aid. Local salmon boats took up the search, and more U.S. ships were called to the area to assist. In Martin's absence, the Air Service named Lowell Smith, pilot of the Chicago, interim commander.

The remaining three planes continued their journey through the Aleutian Islands, battling snow, fog, and williwaws. Williwaws are sudden bursts of icy, capricious winds that rush down from coastal mountains to sea level and can reach 80 mph or more. It made takeoff and landing a special challenge, and even in midflight a plane could get caught by a gust of wind and suddenly soar – or drop – hundreds of feet. On May 9 the planes reached Attu Island, the westernmost island in the Aleutians, where they paused for repairs and to wait out another storm. On May 11, they received news that Martin and Harvey had been found unharmed, but their plane was destroyed.

The Seattle had left Chignik on April 30 in good weather, but about an hour after its departure a heavy fog descended, reducing visibility to near zero. The men tried to climb out of the fog but instead flew into the side of a small mountain. They were fortunate; the plane struck on a gentle upslope that was nearly parallel with the angle that the machine was flying. Several feet of snow was on the ground, helping cushion the impact, and the plane skidded for about 200 feet before coming to a halt. Martin and Harvey were unharmed, but the Seattle was damaged beyond repair. They were about 30 miles northeast of Port Moller, where a cannery was located, and though they needed to get their bearings, they had a general idea where they were.

They struck out on foot on May 2, traveling northwest, but concluded that it was the wrong direction and returned to the plane the next day. On May 4 they left again, this time moving southwest. The men battled snow blindness, thick forests, and snow up to four feet deep, and their meals consisted of liquid rations that they brought from the plane. Finally, on May 7, they found a trapper's cabin – vacant, but there was flour to make pancakes, some pickles, and salmon. They ate and slept for nearly three days and regained their strength. On May 10 they struck out again, following the beach toward Port Moller, approximately 20 to 25 miles away. At midafternoon they saw the cannery in the distance. Soon after, a nearby boat picked up the two men and took them the last four miles.

The Far East

While Martin and Harvey awaited their return to the U.S., the remaining fliers continued the journey. They crossed the International Date Line on May 15/16 and touched down off Bering Island east of the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Soviet Union. The Soviets had not given the Americans permission to land, but the U.S. ship Elder was nearby and the men spent the night there. The following day they left for Japan, and in doing so became the first aviators to cross the Pacific Ocean. They landed offshore near Paramushiru in Japan's Kurile Islands (now under Russian control) and flew southwest over the next few days, arriving in Tokyo on May 22.

In Tokyo the men did extensive work on their planes and found some time to take in the sights of the city. They dutifully attended the many receptions put on by their hosts. Their stay was made more enjoyable by an unusual happenstance. Japan had been struck by a major earthquake the preceding September, and the water was still not considered safe for drinking. In its stead, the fliers drank beer. Prohibition was in effect in the United States, so this was a treat indeed. "God how we hate it," quipped the Chicago's mechanic, Leslie Arnold, in his daily report on May 29.

They left Tokyo on June 1 and flew southwest along Japan's eastern coast, arriving at their final Japanese destination, Kagoshima, late the next day. On June 4, the Boston and New Orleans flew across the East China Sea to Shanghai while the Chicago joined them the following day. Up to this point there had been talk of Martin rejoining the group in a replacement plane, perhaps in Europe, and resuming his command for the remainder of the flight. But more than a month had elapsed since his crash. Martin and Harvey did not reach the U.S. from Alaska until May 25, and the major himself put a damper on this talk soon after his arrival, pointing out that there wasn't another plane available (though the prototype plane could have been made ready). He added, "I hope I'm not asked to crowd out one of the boys who have carried on this far. It wouldn't be fair" ("Major Martin May …"). Moreover, interim commander Lowell Smith had proved his mettle time and again since taking over in Alaska, and his navigational skills had won the admiration of the rest of the team. It was June 3 in Washington, June 4 in Shanghai, when it was announced that Martin would not continue the flight and had asked that Smith become the permanent commander. He returned to his home in Bellingham and waited for the remaining crews to complete the trip.

The fliers left Shanghai on June 7 after encountering a problem that plagued them on much of their flight through Southeast Asia. The waterways used for takeoff were often crammed with native boats, making departures and landings tricky; in Shanghai, the New Orleans was forced to abort a takeoff attempt after being cut off by a boat. The planes proceeded southwest along the Chinese coast to Hong Kong, where they landed in a heavy rainstorm the next afternoon. There they made minor repairs to their planes, including replacing a pontoon and welding a leaky cylinder jacket on the Chicago.

The planes continued southwest. The repairs to the Chicago's cylinder jacket proved to be temporary, and by June 11 it was leaking again. It suddenly worsened and the engine began smoking as the fliers neared Tourane (now Da Nang) in Annam, a French colony in what is now Vietnam. The Chicago hastily landed in the water near Hue, its motor ruined. The other two planes landed long enough to ascertain what had happened and to confirm the men were unharmed, then flew to Tourane and summoned help. In the meantime, Smith and Arnold were entertained, first by the natives and then by a couple of priests who happened by and plied them with wine and water. The water was not purified, and Smith soon developed a stubborn case of dysentery, which lasted off and on for more than a month. The Chicago's fliers were rescued early the following morning and towed by native canoes to Hue. A new engine was shipped from Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), and Smith and Arnold joined their fellow travelers in Tourane on June 15.

Halfway Point

On June 16 they flew to Saigon, where they struggled with the heat and calm waters that hindered their ability to get aloft. (The pilots developed a technique where a lead plane would generate a wake sufficient to give other fliers enough lift to take off, but this didn't always work. Even when it did, it still left the lead plane in the water.) They lightened their planes by cutting back on their fuel load, but this meant more refueling stops as the planes turned west, flying first to Bangkok and then to Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar), where they were delayed for several days. Smith suffered an attack of dysentery and was forced to rest for a few days, and the New Orleans needed repairs after a native boater accidentally clipped the plane's right wing. On June 26 the aviators reached Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, and took up quarters at the city's Great Eastern Hotel. It wasn't quite the halfway point of the trip, but psychologically it felt like it.

Further reading: In Part 2, the fliers successfully complete their circumnavigation of the globe.