On November 22, 1946, after more than two years of effort by a group of philanthropists led by Emil Sick, Rainier Brewery president and owner of the Seattle Rainiers baseball club, the King County Central Blood Bank opens in Seattle's First Hill neighborhood – one of the first centralized blood banks in the nation. The blood bank is one of many health organizations championed by Sick. In a community-wide appeal, he raises $200,000 for construction while Seattle physician S. Maimon Samuels and his wife donate the land on the corner of Terry Avenue and Madison Street. The building includes a space where volunteers can rest comfortably while donating blood and a two-story annex with a well-equipped laboratory. About 900 people attend the dedication of the new building; Sick and Samuels are the featured speakers. The public is invited to tour the new building from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. on Sunday, November 24.

A Novel Concept

Before World War II, individuals who needed a blood transfusion had to wait, often hours. First family members, friends, and business associates were contacted to see if their blood was compatible. If a donor was found, the blood was collected and processed. The entire procedure could take hours, and patients often died before they could receive the needed transfusion.

In Seattle, physician Eugene B. Potter came up with the novel idea of starting a centralized county-wide blood bank that would use volunteer donors to create a blood inventory that could be searched for compatibility and the blood delivered quickly to physicians and area hospitals. With help from other physicians and community leaders, the idea caught on and the King County Central Blood Bank filed articles of incorporation in Olympia on May 20, 1944. The blood bank initially set up operations in King County Hospital, which later became Harborview Medical Center. It was Washington’s first community-wide blood-supply system and one of the first in the nation.

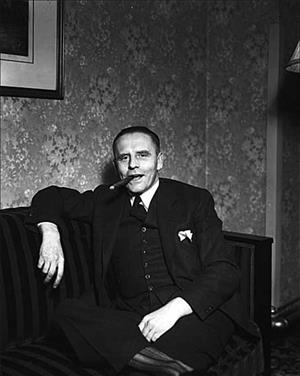

Potter was elected president of the blood bank on June 10, 1944. Intent on creating a stand-alone facility, blood-bank supporters asked Seattle businessman and philanthropist Emil Sick (1894-1964), president of Rainier Brewery and owner of the Seattle Rainiers baseball team, to lead the campaign to raise funds for a dedicated building. Within a year, more than $140,000 out of the needed $200,000 had been promised. About $100,000 came from 20 individuals who each wrote checks for $5,000, including Sick. The names of the founding members, inscribed on a plaque inside the new building, included some of Seattle’s most venerable families and business owners.

An astute, hard-working, and incredibly successful businessman, Sick spoke often about the importance of public service. "In all his affairs, Sick brings to bear a rare combination of the practical and the cultural. He feels that a broad social outlook is as important as sound business judgment. The modern executive, in his opinion, must have an understanding of human values and the ability to evaluate and foresee economic and social trends in order to direct a large industrial organization in a socially acceptable manner" ("Emil Sick Shows, By Action Not Words ...").

It took more than two years to design and build the King County Central Blood Bank headquarters. Physician S. Maimon Samuels and his wife donated the property at the corner of Terry Street and Madison Avenue. "The small, original building had two sections: a one-story donor center, and a two-story annex and laboratory for testing and processing blood. The new community blood bank was called on to perform two vital functions. First, to collect and distribute blood to patients in hospitals across the region without regard to a patient’s income or social status. And second – because transfusion was a relatively new medical procedure – the center took a leadership role in spearheading research to extend the shelf-life of blood components, to improve transfusion practices and safety, and to help people with bleeding disorders" (Bloodworks Northwest: A Concise History).

Community Support

An additional $10,000 to buy equipment for the blood bank came from the state’s war emergency fund. Scores of civic organizations, businesses, and individuals became sustaining contributors by making gifts up to $1,000. These included Women’s City Club, Imperial Candy Company, Italian Club, Northwest Casualty Company, Olympic Hotel, J. C. Penney, Rayonier Inc., Washington Iron Works, Washington Athletic Club, and many more. More than 20 labor unions representing workers from aero mechanics to bakery salesmen, retail clerks to produce drivers, also participated. The American Federation of Labor Teamsters Union pledged $15,000 and the Congress of Industrial Organizations another $10,000.

Sick was delighted with the response. In a newspaper interview, he claimed it "has exceeded our best expectations. Because of the excellent cooperation of the community as a whole, the finest specialized institution of its kind in the nation will be located in Seattle. And, best of all, permanency is guaranteed" ("$140,000 is Subscribed to County Blood Bank").

Emil Sick

Whether leading fundraising drives, managing breweries in the U.S. and Canada, or running a pennant-winning baseball team, Emil Sick enjoyed a challenge. Born in Tacoma on June 3, 1894, he was raised in Alberta, Canada, where the family ran a brewery business started by his German-born father Fritz Sick (1859-1945). In 1933, Emil Sick, his wife Thelma Kathleen "Kit" MacPhee (1899-1962), and their four children moved to Seattle, where Sick opened Century Brewery, which became the Rainier Brewing Company in 1970.

In 1937, Sick purchased the last-place Seattle Indians baseball team and with $350,000 of his own funds, built a new stadium for the team in Rainier Valley. With an infusion of funds and talented players, the Seattle Rainiers began an upward trajectory. "As a baseball club owner he gave Seattle five pennant winning seasons with many memorable teams, and heroes who lasted through the ages. Beyond that, Sick was a dynamic civic booster, a man who could get things done and who contributed so much to his adopted city" (Flynn). The affiliation with the blood bank was one of Sick’s many charitable interests. He was also state chairman of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, chairman of the Green Cross for Safety Campaign, and raised funds for the March of Dimes. He also helped raise $100,000 so St. Mark’s Cathedral could pay off its debt and make building improvements, and raised another $100,000 to build Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry, which opened in 1952. He died of a stroke at Swedish Hospital on November 10, 1964.

Bloodworks Northwest

King County Center Blood Bank quickly became a model blood center; requests flowed in from other U.S. cities interested in establishing similar operations. As the decades passed, the blood bank continued to innovate. The first bloodmobile was introduced at the Bellevue Square parking lot in 1955, allowing donors to give blood where they worked or shopped. The blood bank was first in the nation to use plastic bags for blood collection, and its research discoveries, such as ensuring longer shelf life for platelets, led to improved surgical procedures and saved more lives.

In his 1970 book, The Gift Relationship, Richard Titmuss, a sociologist at the London School of Economics, called the King County Blood Bank "one of the best organized and effective blood banks in the United States ... In other cities, blood is generally collected and tested in each hospital, not in a central laboratory. Here, just a main laboratory and a smaller satellite facility, both run by the private, nonprofit King County Central Blood Bank, do 120,000 tests for the transfusions needed by its residents ... Blood bank officials said that such centralized, nonprofit testing eliminated the large profits that hospitals and doctors can make in other cities. Further, blood bank officials say they do not pay any donors, and are able to meet the entire community’s needs" ("Seattle Blood Bank Cuts Cost and Risk of Infection").

As donor centers were established in nearby counties, the center was renamed Puget Sound Blood Bank in 1974. The original building at Terry and Madison was demolished in 1981 and a new center built in 1984. Another name change was in store when the blood bank was rebranded Northwest Bloodworks in 2015. As of 2023, it supports 900 employees, 2,400 volunteers, and 12 donor centers.