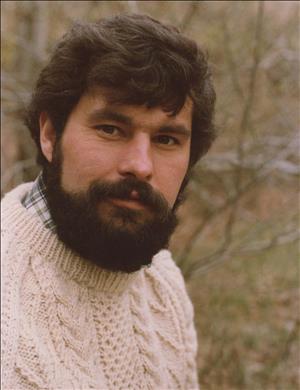

After discovering the joys of wine at age 21 during a trek across Europe and Asia, Ron Irvine (b. 1949) has spent the rest of his working life immersed in the Washington wine industry. In 1971, having just returned to Seattle from overseas, Irvine joined the push to save Pike Place Market, and in 1975 he and two business partners founded the Pike and Western Wine Shop in the heart of the Market. In the 1990s Irvine turned his attention to researching and writing a book about the history of Washington wine. The result was The Wine Project, authored by Irvine with an assist from Dr. Walter Clore, the celebrated "Father of Washington Wine." In the late '90s Irvine purchased a winery on Vashon Island and spent the next two decades as a vintner, until the COVID pandemic helped push him into retirement in 2020.

Roughrider

Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, on February 25, 1949, Ron Irvine was 2 when his family moved to Seattle. The Irvines had been happy in Canada, with a sprawling extended family nearby, until Ron's father Herbert Irvine (1913-1989) lost his job under unusual circumstances. A Royal Canadian Mounted policeman, Herbert was fired after he declined to shoot a man attempting a prison escape. "So they fired my dad," Irvine said, "and he was so pissed off at them, at the province of British Columbia, that's when they decided to move" (Irvine interview). Herbert packed up his family and headed to Seattle, bought a house on 15th Avenue NE at NE 70th Street, and settled into a middle-class lifestyle. He worked for several employers before starting a long career at Wick's Appliance store in the Greenwood neighborhood. Ron's mother Eleanora (1910-1999) sold Van de Kamp's baked goods at a nearby Tradewell grocery.

Irvine said there wasn't much wine drinking at home, but there were plenty of animated moments around the dinner table involving Ron's older brothers – Allan (1939-2000) and James (1942-2017), both amateur boxers – and his older sister, Elinor Gayle (b. 1940). "My mom made some wine, she made fruit wine primarily," Irvine recalled. "I liked the magic of it, but I didn't do anything with it. But no one else drank wine; they all drank beer or liquor. My brother Al had a definite problem with alcohol ... So I learned about alcohol through those guys. I remember there was a bottle of Thunderbird up on the top shelf in our kitchen. My mom kept it there" (Irvine interview).

The Irvines weathered a crisis in 1957 after Allan was pummeled in the boxing ring by welterweight opponent Quincey Daniels. Daniels would win an Olympic bronze medal at the 1960 Summer Games in Rome. Allan laid down after the fight and didn't get up. "He was in a coma for three or four months at Cabrini Hospital," recalled Irvine, who was 7 at the time. "It was scary. They kept the lights down low. I would go into the chapel and be by myself. It was cold and dark, not very inspiring. But he recovered and became a barber, and he was a barber for most of his life ... Jim was a boxer, too. He was tougher than Al, just a tough [expletive]. He wasn't afraid of anything or anyone ... He used to throw himself down the basement stairs just for the hell of it" (Irvine interview).

Ron chose a gentler path. He and his friends spent hours up the street at Froula Park, where Irvine developed a lifelong passion for tennis. When he was old enough, age 16, he got a job at Dick's Drive-In on Broadway. He attended Roosevelt High School, lettered in tennis, participated in the Roughriders service organization, and pondered his future. "I thought I would be a sociologist, and I didn't even know what that meant, other than to help people, and I wanted to help people. And then I wanted to be a psychologist. That's what my (University of Washington) degree is in. I had a chance to use it; I worked for Community House up on Capitol Hill, in the era when Nixon was president ... patients were turned out on the streets, they had no money ... I enjoyed working with those people" (Irvine interview).

Adventures in Europe

Irvine had nearly completed his degree requirements when he decided to take a break from college and see Europe with friends. He financed the trip with money he had saved working at Dick's. The others bought round-trip tickets, but Irvine's was only one way. "I knew I wasn't coming back for a while," he said "("Ron Irvine's 'Wine Project' ..."). When he finally returned to Seattle in 1971, he had been overseas for a year and a half.

Irvine had expected to drink lots of Heineken Lager on the trip, but then he met a woman in the Netherlands who introduced him to the simple pleasures of wine. "She was a stewardess for KLM with a second-floor apartment above a bakery," he recalled. "She would take me to this business where they sold just wine, bread, and cheese, and that was our dinner" (Irvine interview). He then traveled to Switzerland, where he stayed in a commune and drank wine in taverns, and then on to Istanbul, where he hooked up with an old hippie who was biding his time in Europe, waiting for his grandmother to die so he could claim an inheritance. From Turkey they journeyed overland to India, and then Irvine continued east to Thailand. He was teaching English in Bangkok when he decided to return home.

Irvine's formal wine education began in 1974 after he got a call from Jack Bagdade, a charismatic doctor and civic activist; he and Bagdade had met in 1971 when both joined the Alliance for a Living Market in hopes of saving Seattle's Pike Place Market. The alliance provided political support to Victor Steinbrueck, the face of Market preservation efforts, and in November 1971 Seattle voters approved a measure saving the Market from developers. Irvine was working as a delivery driver when Bagdade called. "He called me one day and asked me if I wanted to open a wine store. That was the first time I'd thought about it, though I had been drinking wine, in Holland, and France, and Spain. I found that I liked wine better ... I liked the flavor, I liked the high that I got from it, it was kind of exotic. But I didn't start learning about wine until Jack called me" (Irvine interview).

Pike and Western

Bagdade and Irvine found a space in the lower level of Pike Place Market, down the ramp from City Fish, and opened Pike and Western Company Wine Merchants in August 1975. Bagdade, who was a fulltime doctor, and a third partner, Leo Butzel, provided the money. Irvine would build equity by managing the shop. "We were at the very cutting edge, and we knew it," Irvine said. "At the time, there were only three wineries in Washington. In Oregon, there were four. We decided early on that we were going to feature Northwest wines, and we did. Our whole philosophy was that we were in the Pike Place Market and people would shop the Market then come by and buy a bottle of wine" ("Ron Irvine's 'Wine Project' ...").

Irvine immersed himself in the rhythms of the Market. He volunteered as a board member for the Pike Place Market Development Authority, which owns and develops properties in the Pike Place Market Historic District. In 1977, he sold his car and moved into an apartment in the renovated Triangle Building, just steps from the Pike and Western store, which by then had relocated from the lower level into a more visible storefront in the Soames Dunn Building on Pike Place. "The key to the market is accessibility to everybody," Irvine told The Seattle Times in 1977. "You can stumble on to something here – like wine, for instance – and suddenly realize for the first time that it's all not the same" ("Designer Hill"). In his 1997 book The Wine Project, Irvine writes:

"From the beginning, Pike and Western featured the wines of the Pacific Northwest, including wines from Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. I can still look back and see the shelves of that first store and the small selection of Northwest wines: Ste. Michelle, Tualatin, Knudsen-Erath (and Erath separately), Puyallup Valley Wine Cellars, Veredon, Timmens' Landing (Salishan), Associated Vintners, and Boordy" (The Wine Project, 19).

At the same time, Irvine was informing Seattle's fast-growing population of wine enthusiasts. He taught wine courses in conjunction with the nonprofit Market School – one for novices, "one for varietal intermediates, and a third for restaurateurs who want to learn more about matching proper wines and foods" ("Market Merchants ..."). In the late 1970s, Irvine and Richard Malia founded the "Dinner with the Winemakers" series at Malia's Seattle restaurant; Irvine helped select the wines and "brought in the winemakers for spirited dialogues with diners" ("Host of the Town"). By 1985, wine appreciation had become hugely popular in the region; the Pacific Northwest Enological Society swelled to more than 4,000 members, "all with an undying enthusiasm. Monthly tastings and yearly festivals are sold out the minute they are announced" ("Profile of a Washington State Wine ..."). At Pike and Western, Irvine told The Seattle Times, "I would say that our typical consumer is an intelligent buyer who experiments and tries new things. He is willing to pay a little bit more for good wine, too. Most wines sell for $3 to $5, but local customers are willing to pay $8 to $9 for something better" ("Profile of a Washington State Wine ...").

In 1978, Irvine met his future wife, Ginny Nichols, while conducting a wine tasting for a women's soccer team on Vashon Island. A romance ensued. The following year he and Nichols bought a house on Vashon at Ellisport, and in 1982 they were married aboard the Gallant Lady on Puget Sound. "Daisies, tulips and small potted trees decorated the bow, and the bride and groom exchanged a dogwood and split leaf maple tree as symbols of their growing love," reported the Vashon-Maury Island Beachcomber ("Remember When ..."). Irvine and Nichols have lived in the same Ellisport house ever since; they raised their children Andrew (b. 1983) and Claire (b. 1987) there.

The Wine Project

In 1991, Irvine sold his interest in Pike and Western to Michael Teer, a shop employee and jack of all trades whose expertise enabled Irvine to pursue his other interests. Teer was still running Pike and Western 33 years later. Meanwhile, Irvine went looking for new adventures. In The Wine Project, Irvine writes that he first met Walter Clore (1911-2003) in the 1980s at a wine party in Prosser. After Irvine left Pike and Western, "One of the first things I did was to call Dr. Clore and arrange an interview" (The Wine Project). Clore was then in his 80s but still active as a consultant to Washington growers and winemakers, most notably industry giant Chateau Ste. Michelle. After some back and forth, Irvine and Clore agreed to collaborate on a book. Clore would share his expertise and Irvine would do the writing. "It was really kind of his idea," Irvine recalled. "It naturally felt good to write his story, which is the story of Washington wine, really" (Irvine interview).

The men spent six years doing research, and Irvine wrote the manuscript in 18 months. In the book's preface, he writes that the project, like grapevines, "required sustenance and a foundation. It required a root structure, and material to be built, word by word. It grew shoot by shoot, leaf by leaf, and cluster by cluster – vignettes in the truest sense of the word. It required pruning and shaping, cutting, slashing, and rebuilding. Still, that wasn't enough: it needed a design, a form; then it needed to be printed, distributed, and sold. And it needed an audience" (The Wine Project, 10). The book did find an audience, Irvine said, selling more than 4,000 copies. Later, when Irvine taught wine courses at South Seattle Community College, The Wine Project was his textbook.

The Wine Project begins in 1992 with Irvine and Clore climbing into a small airplane piloted by Mike Hogue (b. 1944) for an aerial tour of the Yakima Valley. In subsequent chapters, Irvine and Clore explore such out-of-the-way places as the Lewiston-Clarkston Valley, Stretch Island, East Wenatchee, Hoodsport, La Center, and Bingen. They also visit emerging hot spots in the state's wine industry – Red Mountain, Red Willow Vineyard, Sagemoor Farms, Horse Heaven Hills, and on more than one occasion, Walla Walla. Irvine delves into the history of Washington grape growing and winemaking, starting with the first plantings at Fort Vancouver in 1825. He profiles Yakima Valley wine pioneers William Bridgman and E. F. Blaine, devotes an entire chapter to the Seattle-area group that founded Associated Vintners, and traces the meteoric rise of Chateau Ste. Michelle.

Clore is the story's central figure. Honored by the state legislature in 2001 as the "Father of the Washington Wine Industry," Clore grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, studied horticulture at Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State University), then moved to Pullman and Washington State College (now University) "for a half fellowship that paid $500 a year" (The Wine Project, 20). In 1937, Clore was appointed assistant horticulturist at WSC's Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser, and in 1940, using cuttings supplied by William Bridgman, he planted vinifera grapes. "With them, Clore established the state's 'mother block' at the research center, and he would add to it over the years with European vinifera stock from California, British Columbia, and Europe ... In 1960, he began field trials to test the viability of the center's vinifera vines in other locations and to convince growers they could harvest quality wine grapes if they implemented his agricultural practices" ("The Legacy of Walter Clore").

Irvine writes about Clore's colleagues: Vere Brummund, hired as a technical aide at the research center in 1957; Chas Nagel, a food technologist who made the center's first wines in 1964; and George Carter, the center's winemaker from 1967 to 1977. Irvine revisits a day in the 1960s when Brummund, Nagel, Carter, and Clore gathered to taste an interesting new wine. "Quite a group. Vere Drummund, acrimonious and combative, but committed to vinifera-based wines; Chas Nagel, skeptical and absorbed in his scholarly work but helpful, encouraging, and curious; George Carter, eager, methodical, committed (and a little playful); and Walt Clore, dedicated, resourceful, and inquisitive" (The Wine Project, 221). Irvine reaches the inescapable conclusion that Clore and his colleagues provided much of the scientific know-how for a Washington wine boom that was just getting started. When Irvine finished writing The Wine Project in 1996, there were 90 wineries in the state. They were producing 7 million gallons of wine, and total sales of Washington wines amounted to more than 6 million cases. By 2024, the state's 1,050-plus wineries were producing more than 17 million cases, and Washington was the nation's second-leading wine producer after California.

In The Wine Project epilogue, Irvine and Clore drive around Eastern Washington, stopping at Sagemoor, Canoe Ridge, Gordon Brothers, and Columbia Crest before returning to Prosser. "The Yakima Valley was absolutely stunning in the late afternoon; the sun, which was on our left, sent horizontal yellowed sunrays shooting across the valley," Irvine writes in the book's closing paragraph. "I'm sure it was an optical illusion caused by my van's windshield, but in that moment it was dramatic and poignant: In that giving, golden yellow light, I clearly saw the purpose of this book, of passing on the knowledge from Dr. Clore's generation to my own, like propagated cuttings from one vineyard to the next" (The Wine Project, 404).

In 2005, Seattle Times wine writer Paul Gregutt was asked about the best books on the Washington wine industry. "For history, the best book remains Ron Irvine's The Wine Project," Gregutt wrote. "Though written almost a decade ago, it covers the first 150 years of the region's viticulture in an exhaustive yet highly personal account" (Gregutt, "Wine Q&A").

Cider Master and Vintner

Well before he left Pike and Western in 1991, Irvine had been spending time closer to home at Vashon Winery, where he'd gotten to know winery owners Will Gerrior and Karen Peterson. Irvine was happy to work there a few hours a week; he would continue to do so while working on The Wine Project. "It was a wonderful way of writing a book, to immerse yourself into making wine while writing about wine," Irvine said. "I really got so much done just sitting on a forklift, moving barrels of wine. That’s where I learned to make wine" ("Ron Irvine's 'Wine Project' ..."). In 2002, a few years after the book was released, he purchased Vashon Winery from Gerrior and Peterson. "One of the reasons why I bought the winery, originally, is that I wanted to be a producer," he said. "I wanted to make something – it could have been art or something else – but being responsible for something and producing something with your own hands is a wonderful thing" ("Final Harvest ...").

Vashon Winery would be Irvine's labor of love for the next 20 years, though various side projects also kept him busy. In the late 1980s he took an interest in making cider from Washington apples, and in 1988 he began producing a limited annual run of Centennial Cider, a 7-percent-alcohol drink corked in wine bottles at Vashon Winery. Later, Irvine focused on making varietal cider from a single type of apple, the Kingston Black. "I've kind of decided, at least intellectually, that I would never be crazy enough to do this as a business," he told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1997. "But emotionally, it drives me crazy that there is a market there and no one is really reaching it. So I've tried to encourage others by example, and maybe the big guys will move in" ("'Hard' Pressed ...").

According to Steve Roberts in his 2007 book Wine Trails of Washington, Irvine was essentially a one-man band running a winery: "In Vashon Winery's barn-like tasting room, a chandelier hangs from the rafters, a basketball hoop graces the wall, and the sign above the tasting bar reads 'Ron Irvine, owner, winemaker, janitor'" (Wine Trails ..., 100). Of the wines, Roberts writes:

"At the Vashon Winery, visitors have an opportunity to sample Ron's full portfolio of reds and whites as well as his European-style hard ciders. Ron relies on grapes from Yakima Valley-based Portteus Vineyards, which include cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc, and merlot. The white wines, such as Ron's smooth and crisp semillon and sauvignon blanc, are made from grapes grown by Eastern Washington growers. For a real treat, check out his wonderfully named 'Isletage' (rhymes with Meritage), which is a blend of Puget Sound-area grapes: Madeline Angevine, siegerrebe, and Muller-Thurgau. He also makes wine from a relatively obscure island-grown varietal called chasselas, best known in Switzerland" (Wine Trails ...,100).

By the late 2000s, Irvine was making more Pinot Noir from grapes grown on Vashon Island. He began making half of his wines with Eastern Washington grapes and half from grapes grown in the colder, wetter, and more challenging Puget Sound AVA. At the winery, Irvine welcomed visitors for wine tastings "in what he calls a 'garagiste' winery, a moniker used in Bordeaux, France, to describe garage-size wineries that make wines without their own vineyards. Look for the landmark red barn where Irvine produces just 600 cases of wine, much of it made with 'cool climate' grapes he buys from vineyards on Vashon and others around the Sound" ("Day Tripper ...").

A Way With Words

Irvine, wrote the local Beachcomber newspaper in 2020, did his best to make Vashon Winery a community gathering place:

"The winery, under Irvine's ownership, has served as a kind of clubhouse for local poets and musicians, where readings took place indoors amid the oak wine barrels, and where folk singers gathered to play on the expansive, sun-dappled grounds ... It was at the winery that Irvine and other high-minded co-conspirators got their ideas for such events as the bi-annual Vashon Poetry Festival ... Other projects, helmed by Irvine, have included the one-time-only ReadOnWriteOn Vashon book festival, and a re-creation of the historical Chautauqua in Ellisport. The winery has also been the site of many musical performances – both at Irvine's own Vashon Folk Festival, which he produced for three years, and other one-off events" ("Final Harvest ...").

In October 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic creating a netherworld of lockdowns, Irvine announced plans to sell Vashon Winery and ease into retirement. "He's not sure what will come next for him, after selling the winery," reported the Beachcomber. "Perhaps a move to California with his wife, Ginny Nichols, to live closer to their now-grown son and daughter. Nichols is the long-time owner of her own island-based upholstery business, Phoenix Upholstery. Irvine admits that is hard to image leaving. 'I love my lifestyle, I love the house and the woods and the beach and our neighbors and I look forward to going home,' he said. 'But I do look forward to just having time. I've worked on Saturdays since I was 16 years old'" ("Final Harvest ..."). In 2024, Irvine had yet to find a buyer, and he and Nichols were still living happily on Vashon Island.