Journalist Edmund "Ed" Joseph DeValera Donohoe, whose column "Tilting the Windmill" ran weekly in the labor newspaper The Washington Teamster, was born in Seattle in 1918. The fifth of nine children, he graduated from Seattle Preparatory School, attended college for two years, and joined The Washington Teamster in 1941. His editorial career was interrupted by World War II, where his bravery in the South Pacific earned him a Bronze Star. After the war, he returned to The Washington Teamster and began his signature column in 1950. He quickly became known for his colorful, irreverent, and, some would say, malicious, treatment of Seattle’s power elite. Donohoe was on the board of directors of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the Pacific Northwest Research Foundation, and helped organize and emcee the popular Mid-Winter Sports Banquet, an annual institution for more than 30 years. He retired from The Washington Teamster in 1984, although his passion for politics and labor issues continued. He died on November 25, 1992, at the age of 74.

From Paper Route to Newspaper Columnist

Veteran editor and Washington Teamster columnist Edmund "Ed" Joseph DeValera Donohoe was born in Seattle to financier Thomas J. Donohoe (1870-1928) and his wife Eileen Brady Donohoe (1885-1982). Ed's parents were Irish immigrants who arrived in Seattle around 1910 from Killeshandra, County Cavan. Ed was the fifth of nine children, composed of seven sons and two daughters. His siblings were Michael (1911-1961), Eileen (1912-2001), Eugene (1914-1971), Thomas (1915-1985), Daniel, James (1921-1993), Madeleine (1925-2004), and Leo Patrick (1927-2011). The family was deeply rooted in Seattle’s Irish-Catholic community, first on Queen Anne Hill and then on Capitol Hill.

Donohoe attended Seattle Preparatory School, and for two years was a student at St. Martin's College, a private college in Lacey run by the Benedictine order. More than four decades later, in 1982, St. Martin’s recognized Donohoe as an outstanding alumnus, an honor that seemed to surprise him. "'I only went there two years and was invited not to come back,' he recalls. 'Actually, I think I was kicked out.' He’s crushed by the honor. 'I must be losin' my touch,' he growled, adding: 'I’ll believe this thing when I see it'" (Andrews).

Donohoe’s introduction to the newspaper business was via a paper route he began at age 14. While a teenager at Seattle Prep, he covered sports for the school, finding that writing appealed to him. "While in college he was the campus correspondent for The Seattle Times, but eventually rubbed the editors the wrong way. He was also a publicist for Seattle University and took credit for changing its team names from the Maroons (often mocked as the 'Morons') to the Chieftains [now Redhawks]" ("Ed Donohoe Begins Writing His Newspaper Column ..."). In 1941, he became an assistant editor at The Washington Teamster, where his career was interrupted by World War II. He served in the South Pacific as a medical corpsman, earning a Bronze Star for bringing out wounded men under fire.

After the war, Donohoe rejoined the staff at The Washington Teamster, where in 1950 he launched his column "Tilting the Windmill" – an assignment he would keep for the next 34 years. Initially intended to be a sports column, "Tilting the Windmill" morphed into a broader format, enabling Donohoe to skewer any individual, organization, or cause that caught his attention. Considering himself a "puncturer of pomposity" (Pryne and Tizon), no one was exempt – whether they were millionaires or lawyers, governors or corporate executives. The column became must reading for every politician and mover-and-shaker in town.

A good education, strong religious beliefs, and civic duty were important attributes in the Donohoe family. His oldest sibling Mike became executive sports editor at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and a recognized authority on horseracing. After Mike’s unexpected death in 1961 at the age of 50, his contributions to racing were recognized by Longacres racetrack, which established the annual Mike Donohoe Memorial race for 2-year-olds. Thomas became a Roman Catholic priest who was ordained in Rome in 1978, and James became a professor. Ed's sister Madeline, a skilled tennis player and UW graduate, married long-time sports writer Lenny Anderson, who spent 53 years writing for The Seattle Times, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Tacoma News-Tribune, and The Associated Press. Brother Leo worked for more than 50 years at the Los Angeles headquarters of Farmers Insurance.

In 1956, Donohoe married Mildred "Millie" Dorothy Melger (1920-2005). She was born in Walla Walla to ranchers Joseph and Clara Melger. She moved to Seattle in 1941 to work in the shipyards. After the war, she became a model for Frederick & Nelson, The Bon Marché, and other department stores in Seattle and San Francisco. The couple had three sons: Kevin, Tom, and Dan. Donohoe went back to college after the war and graduated in 1961 from the University of Washington.

The Washington Teamster

Launched in 1937 for members of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs and Warehousemen, and Helpers, Joint Council 28, The Washington Teamster was originally published in Seattle as a free monthly newspaper. In 1941, it became a weekly, issued every Friday, and covered local and national labor-related news meant to foster a sense of solidarity, community, and pride among its members. Topics were varied and might include the signing of a new produce contract in Aberdeen, safety awards won by trucking firms, or the results of a March of Dimes campaign. No advertising was sold, but the paper did publish lists of businesses that displayed the union label, encouraging readers to patronize those establishments.

When The Washington Teamster editor Ralph Benjamin retired in 1956, Donohoe took over his job while continuing to write his column, “Tilting the Windmill,” now into its sixth year. Once labeled "the Don Rickles of the typewriter" (Pryne and Tizon), Donohoe used his column to tease, ridicule, malign, and mock scores of politicians, sports figures, even fellow journalists. Coming up with clever and memorable nicknames was Donohoe’s forte. In his column, former U.S. Senator Slade Gorton (1928-2020) became known as Slippery Slade, while former Washington Governor Dan Evans (b. 1925) was Straight Arrow. Chris Bayley, King County prosecuting attorney from 1971-1979, was nicknamed Sugarplums or at times Bambi, and the League of Women Voters became the League of Women Vultures.

Donohoe also went beyond a simple moniker to create wisecracks that became the talk of the town. "Some memorable one-liners from Mr. Donohoe’s lethal typewriter: Former Mayor Wes Uhlman: 'Our prematurely gray mayor is also prematurely dumb.' U.S. Rep. John Miller: 'He talks like he brushed his teeth with Elmer’s Glue.' Former KIRO-TV president and editorialist Lloyd Cooney: 'In a race with a test pattern, Cooney’d come in second'" (Pryne and Tizon).

Donohoe’s son Kevin insisted his father meant to be humorous, not hurtful, but many who were targeted did not buy it. "One victim wrote to him: 'You are a small-town clown, a malicious racist and a bigot. Additionally, you are a gutless maggot, safely and legally hiding behind your perverted idea of freedom of the press'" (Watson). Fellow newspaper reporters and columnists characterized Donohoe’s style as rascally, crusty, acerbic, or cantankerous.

Although most of Donohoe’s criticism was directed in the political arena, anyone was fair game. He skewered the board of directors at the University of Washington, the 1962 World’s Fair, even Pike Place Market. The University of Washington athletic department was so fearful of Donohoe’s wrath that it once give him press credentials to attend all Huskies events, even though he never covered the games. "'There is nothing subtle about a Donohoe attack,' former Times reporter and columnist Don Duncan wrote in 1980. 'It is like being run over by a Mack truck, or being in a street fight, with knives'" (Pryne and Tizon).

Love it or hate it, Donohoe’s fearless style of journalism sometimes righted a wrong or influenced an outcome. In 1956, "a right-to-work initiative reached the ballot, and editorials in The Washington Teamster rallied working people to work for its defeat. Donohoe later claimed that the campaign also led to the Republican loss of majorities in both houses of the State Legislature" ("Ed Donohoe Begins Writing His Newspaper Column ...").

During the column’s run of 34 years, Donohoe was sued for libel once, but the case was dismissed. Dave Beck (1894-1993), president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters in the 1950s, once commented that, "Donohoe often angered local politicians, but always brought honor to the labor union … There was a lot of opposition to him, but he was the best [columnist] in Seattle" (Tewkesbury). His column elevated The Washington Teamster to national prominence and circulation soared, perhaps helped in part by the free subscriptions Donohoe would send to his favorite targets.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer once tried to muscle in on Donohoe’s magic formula but the action backfired. "In a misguided attempt to raise circulation, the P-I … once hired Donohoe to write for it. Eight months later a team of white-faced, horrified libel attorneys urged the paper to have second thoughts. So he was fired" (Watson).

Doer of Good Deeds

Despite his wicked pen, Donohoe generously served many causes. He was a founding board member for the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, helping to guide the organization for 15 years. He was involved with the Pacific Northwest Research Foundation, Washington Commission for the Humanities, and KCTS-TV. Every year, he would emcee a charity luncheon for the Catholic Seaman’s Club, a Seattle Archdiocese-run organization that provided services, assistance, and recreation for sailors in town on leave. During the event, Donohoe would lampoon every politician and celebrity in the audience; the luncheon was a sell-out every year.

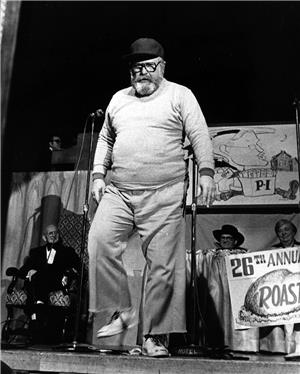

As long-time secretary of the Puget Sound Sports Writers & Sports Casters Association, Donohoe was a driving force behind the annual Mid-Winter Sports Banquet, an irreverent, popular, high-energy event held nearly every year from 1948 to 1980. "He hired the hall, arranged for a speaker, mailed out invitations, rode herd on ticket sales and even approved the menu … Donohoe’s introductory remarks and curtain speeches riveted the audience. For most banquet guests, Ed was the highlight, more enjoyed and applauded than the imported high-cost speakers" ("The Club Without A Muzzle"). By the end of its run, the Mid-Winter Sports Banquet was attracting more than 900 men (and a handful of women). Keynote speakers included some of the most recognizable names in the business, such as former major league baseball manager Leo Durocher (1905-1991), pro baseball catcher and announcer Joe Garagiola (1926-2016), and broadcaster Howard Cosell (1918-1995), among others. When the Olympic Hotel, the banquet venue, announced it was closing for two years to remodel, the sports banquet closed up shop as well. Donohoe wrote about the demise of the popular event in a December 1981 column he called "Last Rites for a Good Club."

Donohoe graciously shared his expertise and connections with political candidates, primarily jurists, introducing them to newspaper editorial boards around the state. In 1974, that included candidate Charles Horowitz. "Donohoe had known – and was impressed by – Horowitz’s legal intellect and background ... Now Donohoe was helping out in the man’s campaign for Supreme Court, knowing that Horowitz, like many judges, felt awkward in the unfamiliar world of the news media" ("Tough Challenges for an Odd Couple"). Horowitz earned the editorial endorsements of nearly every paper in the state and won the election. For nearly 20 years, Donohoe continued to escort select candidates to meet-and-greets with newspaper editorial staffs from Kent to Waitsburg.

He was also a lunch-time fixture at the Four-10, a classy Seattle restaurant run by Victor Rosellini (1915-2003). In fact, Donohoe had his own table there, No. 53. Friend Ed Tyler recalled: "He’d wear his baseball hat and maybe no tie or his tie half-cocked. He’d come to lunch with the most important people in his old rumpled suit while everybody else looked great" (Pryne and Tizon).

The Final Chapter

Donohoe’s reputation continued to grow. In 1980, Arnie Weinmeister, president of the West Coast Teamsters Union, had this to say: "Ed is unique, even if I have to pacify some of the targets of his spleen the next morning. He edits one of the best labor papers in the country. Ed takes on a lot of people, right or wrong, and he raises issues worth thinking about" (Skreen).

Donohoe held himself to the same high standards he demanded of others. In 1982, he resigned from the board of directors at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center as contract disputes between the center and the union dragged on for more than a year. The Teamsters union withdrew its "physical, moral and financial support of the center until a contract is reached .… Donohoe, who has been a Teamster member for 41 years and edits the union newspaper for the state, said his resignation saddened him. 'I feel it’s one of the major decisions of my life,' he said. 'You’re here at the start and then see it grow into one of the top two or three cancer centers in the nation. I really wish that contract could be resolved'" (Jones).

Donohoe retired from The Washington Teamster in 1984, which marked the end of his column as well. He struggled with health issues and underwent several open-heart surgeries. On November 25, 1992, he died at the age of 74. Attendees at his funeral at St. Joseph Church were a veritable who’s who of Seattle luminaries. "If you’d been there, you could have sighted federal Judge Walter McGovern, state Supreme Court Justice Fred Dore, perennial emcee Jack Gordon, restaurateur Victor Rosellini, former assistant Seattle Police Chief Buzz Cook, and Johnny O, who was sporting a new knee" (Godden). After the service, mourners gathered in the church basement to exchange stories and reminisce about Donohoe’s three great lifelong passions: "church, family and the Democratic Party" (Godden).