After a long journey by wagon train from Illinois, William and Sarah Bell and their four daughters arrived in Portland, Oregon Territory, on October 15, 1851. There Bell met Arthur A. Denny (1822-1899), leader of the Denny Party, also from Illinois. The Bells joined that group, sailing north and landing at Alki Point at the entrance to Elliott Bay on November 13, 1851. Three months later, Denny, Bell, and Carson Boren (1824-1912) sought a better place to settle, and in early February 1852 Seattle was founded when the men staked out three adjacent claims on the east side of the bay. Sarah's poor health and the Native American attack on Seattle in 1856 prompted the Bells to move to California that year. There, in less than two years, both Sarah and the youngest daughter, Albina, died. Little is known of the family for the next 14 years. Bell would remarry twice, his third wife a younger sister of Sarah. He returned to Seattle in 1870, prospered with the development of Belltown, and was civically active before becoming disabled by dementia in the early 1880s.

The Bell Family

In 1976 historian Roger Sale wrote of William Nathaniel Bell, "amongst the many accounts of the pioneers he remains faceless" (Sale, 11). A slight overstatement, perhaps, but largely true.

Of Welsh extraction, Bell was born on a farm near Edwardsville, St. Clair County, Illinois, on March 6, 1817, to Jesse (1779-1835) and Susan Meacham Bell (1782-?). His paternal grandfather, Nathan Bell (1755-1835), fought against Great Britain in the Revolutionary War. Nathan's son Jesse (William's father) fought in the War of 1812, then was a United States Rangers volunteer, protecting settlers on the western frontier from the Native peoples whose land was being taken.

Jesse Bell married Frances Southern Hart (of whom nothing more is known) in 1800. They had eight children. After her death, he married Susan Meacham in February 1815. They also had eight children, one of whom was William Nathaniel Bell. William Bell lived and worked on his father's farm in rural anonymity. Nothing more is known of his childhood or adolescence. On March 10, 1840, Bell married Sarah Ann Peter (1819-1856) of Kentucky. Sarah's father, William Taylor Peter, was a minister; her mother, Keziah (or Kesiah) Bailey Peter, a homemaker. Almost nothing more is known about them, or of Sarah's life before marriage.

William and Sarah

The newlyweds moved to a farm at Carlinville, about 33 miles northeast of Edwardsville. Between 1840 and 1851 Sarah gave birth to six girls. Martha Ann (1840-1848) died young and Susan Francis (1844-1845) did not survive infancy. The four who came west with their parents were Laura Keziah (1842-1887), Olive Julia (1846-1921), Mary Virginia (1847-1931), and Albina V. (1851-1857).

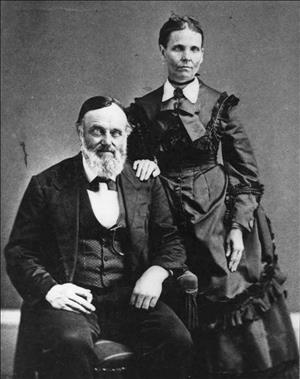

There is only one documented photograph of William Bell, taken around 1880, and he is shown with his third wife, Lucy Gamble Bell. There is no known picture of Sarah. Their oldest daughter, Laura, gave brief descriptions of her parents as they readied to leave for the West. Her father, she wrote, "was thirty three years old, tall, with blue eyes and brown hair" ("William Nathaniel Bell and Sara Ann (Peter) Bell"). She described her mother as:

"a competent housekeeper and very clever in the use of the meager materials at her disposal. She was slender and above average height, had blue eyes, gold brown hair which was like burnished gold when the sun shone on it, and a wonderfully fine complexion. She was a dainty, delicate sort of person who delighted in wearing pretty dresses of blue, pink or lavender muslin and often likened to a bit of Dresden china" ("William Nathaniel Bell and Sara Ann (Peter) Bell").

Dainty and delicate she may have been, but before tuberculosis cut her life short at age 37, Sarah Bell proved equal to the challenges of a dangerous wagon trek across the Great Plains to Oregon and five difficult years on a rugged frontier.

Wagons West

In 1851 the Bell family moved to Alton, about 40 miles away, to join a wagon train headed for the Willamette Valley. They financed their move west by selling their "farm and stock" ("William Nathaniel Bell and Sarah (Peter) Bell") for $1,350. In Alton, Bell built a wagon with a canvas cover to accommodate his family, pulled by a yoke of oxen. Two dairy cows were taken to provide milk during the arduous trek. They also "took their feather beds, packed their clothing and bed covers in bags, and their cooking utensils in a box in the back of the wagon" ("William Nathaniel Bell and Sara Ann (Peter) Bell").

Nearly 270 miles north of Alton, in Cherry Grove, Illinois, the Denny Party was also preparing to emigrate to Oregon Territory. Neither group knew of the other. The Denny Party left Illinois on April 10, 1851, and its experiences were recorded on a near-daily basis by party leader Arthur A. Denny. The last entry in his diary reads "Friday, August 22, Footed it up to Portland" (Watt, 26). The Bell caravan didn't arrive in Portland until October 15, 1851, and no similar record was kept of its passage.

On June 5, 1878, a representative of historian Hugh Howard Bancroft (1832-1918) interviewed William Bell in Seattle's Occidental Hotel. This produced a brief account written in Bell's hand titled "Settlement of Seattle," and a narrative of the interview written by the researcher. Bell said little about the trek west save this:

"The plains were covered with bones of men and women and beasts. Bones were useful in those days. When Indians attacked the emigrants, they [the latter] would write a warning to other emigrants on the white hard bones of former victims … When men were buried their names and epitaphs were written on those bones" ("Wm. N. Bell's Narrative").

The Denny Party and Bell's group made it to Oregon Territory unmolested. Bell's reticence about his family's journey may have been due to what historian Frederic James Grant (1862-1894) later characterized as his "retiring disposition" (Grant, 401).

Changed Plans

Bell and Denny were both dissatisfied with Portland. The city was rife with ague (recurring attacks of chills, fever, and sweating), and most of the best land in the Willamette Valley had already been claimed since the passage of the Donation Land Claim Act one year earlier.

On July 24, 1851, while camped on the Burnt River, Denny had met a man named Brock, who "Gave us information in regard to Puget Sound … My attention was thus turned to the Sound and I formed the purpose to look in that direction" (A. A. Denny, 9-10). Denny, his wife, and one child were stricken with ague in Portland and would not recover until fall. By then the Bells had arrived, and a serendipitous encounter between Bell and Denny led to the Bells joining the Denny Party on the passage to Elliott Bay aboard the schooner Exact.

Alki

On November 13, 1851, the Exact put the expanded Denny Party ashore at what is now called Alki Point. The weather was typical for a northwest November – terrible. Three men had come ahead to scout for the larger group – David Denny (1832-1903), John Low (1820-1888), and Lee Terry (1818-1862). Low was on the Exact, having gone back to Portland to convey David Denny's message to his brother Arthur to "come at once" ("Denny Party Lands at Alki …").

The only structure at the site was an unfinished, roofless cabin. Denny was ill, Terry absent, the scene dismal. In his short, handwritten account William Bell reported that "the Ladys sat down on the loggs and took A Big Cry" ("Settlement of Seattle"), a rather insensitive comment later characterized by Frederic Grant as "artless" (Grant, 53, footnote). In an interview with Grant years later, Arthur Denny wrote with more empathy of his own wife: "I did not think it at all strange that a woman who had, without complaint, endured all the dangers and hardships of a trip across the great plains, should be found shedding tears when contemplating the hard prospects then so plainly in view" (Watt, 40).

After finishing the Low cabin, a log cabin was built for Arthur Denny and his family. With all the suitable nearby logs used up, split cedar planks smoothed with carpenter's tools were used to build dwellings for the Bells and Borens. The Bells' was "the first frame house ever built in what is now King County" (Bell, "Settlement of Seattle").

In early December the brig Leonesa anchored offshore, bound for San Francisco with materials to rebuild that city after a great fire the previous June. In driving rain, the adult male settlers then present on Alki felled trees, rolled them to the beach, and loaded them onto the ship, their first export and first income.

A Better Place

Several members of the Denny Party disliked the Alki site. Terry and Low had filed Donation claims on some of the best land on September 28, 1851, six weeks before the others landed. The point had decent anchorage but was buffeted by frequent winds sweeping up and down Puget Sound. Also, several hundred members of local tribes had set up camp near the settlers. They were neither threatening nor welcoming, but their presence in such numbers caused the settlers some unease.

The experience with the Leonesa had shown a way for the settlers to earn money before crops were in or businesses begun. Bell, Boren, and Arthur Denny, traveling by canoe, began looking for a site that would better serve this purpose. As later reported by Denny: "We had looked up the coast toward Puyallup during the winter and did not like the prospects. In the month of February we began exploring around Elliott Bay, taking soundings and examining the timber" (A. A. Denny, 35). They found what they were looking for on the bay's eastern shore, and on February 15 the men marked three adjacent claims – Boren to the south and Denny in the middle, with Bell taking the northernmost. If any single date could mark the birth of Seattle, this was it.

Before It Was Belltown

Under the Donation Land Claim Act, one half of the 320 acres William Bell staked out would be the property of his wife, Sarah, held in her name. This enlightened (for its time) requirement was intended in part to deter land speculation. To perfect title the law required four years of occupancy and use. Due to illness and war, the Bells would barely make it.

Bell moved from Alki and "settled" his claim on April 3, 1852, a necessary step to perfecting title. In the Bancroft interview, he spoke of those earliest days:

"Borren moved over in some 3 weeks him and myself having made a claim here about a month before by cutting down a tree and notching them dow in the form of a house … I made me a camp like an Indian of Slabs and Mats. Lived in it 2 weeks before I got a cabbin built" ("Settlement of Seattle").

Bell's cabin was the first dwelling completed. On May 23, 1853, Sarah Bell wrote to her mother: "[A] little more than a year ago we came over on this side of the bay and at that time our claim was the only one that was inhabited, not the face of a white person to be seen and nothing to be heard but the yells of the savages" (quoted in "William Nathaniel Bell and Sara Ann (Peter) Bell").

Also on May 23 that year, the first plats of Seattle were filed by Arthur Denny, Carson Boren, and David "Doc" Maynard (1801-1873). Bell kept his claim separate; it was for several years not part of Seattle, but a separate and largely empty entity known as Belltown.

The First Years

Along with the other settlers, Bell worked to clear his land and harvest timber for export on ships enroute to California. Henry Yesler's (1810?-1892) steam sawmill began operation in March 1853, increasing the variety of lumber the settlers could provide. In time they were also able to sell or barter salted salmon and garden crops.

For a retiring man, Bell did not shirk civic duty. On November 25, 1852, barely settled, he was a delegate (together with Arthur Denny, Doc Maynard, and 41 other men) to the Monticello Convention, which petitioned Congress to carve a new territory from the portion of Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River. Barely three months later, on March 2, 1853, Washington Territory came into being. Three days after that the King County Board of Commissioners met for the first time. William Bell was tapped as a petit (trial) juror, and in April was named "Supervisor of Road District No. 1" (Prosch, 40), which encompassed everything north of the Duwamish River. In February 1854 Bell served as a grand juror in the second term of the District Court, and later that year was elected county coroner.

The first mention of Sarah Bell in the history books after the move from Alki came in the winter of 1853. In January that year, David Denny and Louisa Boren (1827-1916) were wed, the first marriage in King County. David had claimed land that stretched from the south shore of Lake Union to Elliott Bay, adjacent to the Bell claim. Louisa became ill that winter, and Sarah Bell walked a mile from her home to visit, taking along grouse eggs. Two Native Americans later arrived, one of them standing in the doorway, silently watching the women. They eventually left. According to John Kanim, a brother of the volatile Snoqualmie chief Patkanim, they had come to rob and murder the Dennys, but were deterred by the presence of a "haluimi kloochman" (an unknown woman), fearing both David Denny and the other woman's husband might be nearby (E. I. Denny, 670; Buerge, 119, 120). There is no way to judge the truth of this account.

There are only random scraps of information about the Bell family before the pivotal events of late 1855 and January 1856. By far the most important was the birth, on January 9, 1854, of Austin Americus Bell, William and Sarah's first son and the second white child born in Seattle. That same year the town's first blacksmith made a plow for Bell, but "he had no animal to draw it, and its usefulness was rusted out instead of worn out" (Prosch, 54). Also in 1854, young Laura, Olive, and Virginia Bell began attending a school founded by Catharine Blaine (1829-1908). She and her husband, David (1824-1900), both Methodist missionaries, had arrived in Seattle in November 1853. Catharine became the settlement's first schoolteacher and David founded the town's first church, known as the Little White Church.

Pioneer life was a shared struggle. The heavy forest prevented good pasturage on the three original claims, and Arthur Denny and Bell had to drive their cows to meadows near Lake Union that local tribesmen had told them about. Cougars and wolves roamed the forest, disturbing the night and taking down the occasional cow. Life was hard, but there was a mood of optimism. For the Bell family that was not to last.

The Attack on Seattle

In 1855 members of several tribes from east and west of the Cascades, angered by the treaties imposed on them by Washington's first territorial governor, Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), took to the woods to wage war against the military and those who had taken over their lands. On October 28, 1855, nine settlers – men, women, and children – were slain on their farms near the White River by members of the Muckleshoot and Klickitat Tribes, the worst Native-on-settler violence of the war. Seattle was attacked on January 26, 1856. William, Sarah, and Laura Bell sheltered in a blockhouse along with several other settlers. Their younger children were taken aboard the U.S. warship Decatur moored in the bay.

Details of the attack are described in multiple accounts. Here it is necessary only to record the effects it had on the lives of the Bell family. At the time, Sarah Bell was ill with tuberculosis. Emily Inez Denny, the daughter of David and Louisa Denny, later wrote:

"Laura Bell, a little girl of perhaps ten years, during her stay in the fort exhibited the courage and constancy characterizing even the children in those troublous times. She did a great part of the work for the family, cared for her younger sisters, prepared and carried food to her sick mother who was heard to say with tender gratitude, 'Your dear little hands have brought me almost everything I have had'" (E. I Denny, 83).

On January 26, Bell wrote to Arthur Denny, who was in Olympia. His letter, which is reproduced in Bagley's History of Seattle, started with the curious phrase "Sebastopol is not taken yet," an apparent reference to the siege of the Russian port of Sebastopol during the Crimean War. Bell continued:

"My house was burned on my claim during the action, but the outhouses are still standing, but your house in town was robbed of flour and perhaps other things on the night of the attack … Only a part of my cattle came in last night."

For the only known time, Bell mentioned Sarah in writing, using a name that apparently only he called her: "Shirley is true grit." But his pessimism was clear: "Should this state of things continue, there will not be six families left here in the spring." He ended, "The Decatur is afloat and most of our women and children on board of her" (Bagley, History of Seattle, 65-66).

William Bell, with an ill wife, no home, five children ranging in age from two-year-old Austin to 12-year-old Laura, feared future attacks. When the battle had ended, the family briefly stayed in the home of Edward Hanford (1808-1884) on Cherry Street. Bell then packed up their few remaining possessions and moved the family to Napa City, California. Little is known of their lives for the next 14 years, which is not surprising. Communication was slow and difficult (telegraph wires to Seattle were eight years away). More important, Bell was no longer present in the town he had pioneered, but living nearly 800 miles away, just an ordinary citizen going about his business, essentially anonymous. Given this lengthy gap in the record, some conjecture is unavoidable.

The (Almost) Lost Years

The Bells' first two years in Napa City were filled with tragedy. Sarah died on June 27, 1856, not long after the family's arrival. Historian Frederic Grant eulogized her as "a most estimable woman who had patiently borne the trials and privations of the first few years of pioneer life on Elliott Bay" (Grant, 400). On May 15, 1857, Albina died, just 6 years old, of an unknown cause. Bell kept the remaining family together until his oldest daughter, Laura, married in 1858, then placed the younger children in boarding school. Since the Napa Valley was rich in farmland and William Bell had been a farmer his entire life, it is likely that this was what he did during these first years.

Now comes an interlude in Bell's life that is short on detail and somewhat mysterious. For an indeterminate time in the 1860s he was living in Nevada, and on May 22, 1866, he married Isabella Willson at Chrystal Peak in Washoe County. In 1868 the couple were living in Colusa, California, about 65 miles northeast of Napa, where William appeared on the voting roles. This marriage is documented, but seldom mentioned by historians or in family memoirs.

About the only other thing that is known of Bell's life between 1858 and 1870 is that in the early 1860s, at the request of either Arthur or David Denny (sources differ), he returned to Seattle long enough to plat and subdivide much of his claim, making it, finally, a part of the city of Seattle. That is when Bell Street was named. In later years Bell would name streets after his daughters Olive and Virginia, and Olive's husband, Joseph Stewart.

The Daughters

William and Sarah's oldest daughter, Laura, married James Elihu Coffman (1835-1869), a farmer, in Vacaville, California, in 1858. The marriage produced five children, and sometime in the early 1870s Laura returned to Seattle to live. On December 21, 1867, the next oldest daughter, Olive, wed Joseph A. Stewart (1830-1889) in Marysville, California. They too returned to Seattle. Census records indicate that nine years after Stewart's death, Olive married Charles W. Stearns (sometimes "Stearus") (1840-?) and relocated to Ohio, then Manhattan, New York. Interestingly, after Olive's death in 1921 she was interred in a Manhattan cemetery with her first husband, Stewart.

The youngest daughter, Virginia, married George W. Hall (ca.1840-?), a furniture manufacturer, on May 22, 1872, in Seattle's Trinity Church. Two years earlier, Hall had helped organize the city's first Oddfellows lodge, in which his father-in-law became a longtime member. Hall served on the town council from 1875-1878, was elected president of the council in 1890, and in late 1891 was appointed to replace Mayor Harry White, who had resigned with four months left in his term. The Halls had three children and were ranking members of what then passed for high society Seattle.

New Home, New Wife

In 1870 William Bell returned to Seattle to stay, accompanied by his son Austin, his youngest daughter, Virginia, and his second wife, Isabella. Her presence in the city is evidenced by two notarized deeds. Under the terms of one, dated May 28, 1870, "William N. Bell and Isabella Bell, his wife" conveyed a piece of property to Bell's fellow pioneer, Arthur A. Denny. Both William and Isabella signed the document ("William N. Bell deed to A.A. Denny …").

Bell filed for divorce from Isabella in King County District Court in February 1872. Later that year he went to Illinois and married Lucy Peter Gamble (1823-1909), a younger sister of his first wife, Sarah. Lucy was the widow of John H. Gamble (ca.1818-?), whom she had married in 1843. They had four children, three boys and a girl, but when she came to Seattle in 1872 only her young daughter, Leola (1866-1935), remained with her. Leola was identified as William's stepdaughter in the 1880 census. Almost nothing has been recorded of Lucy and Leola's lives while in Seattle. Lucy moved to Antelope, Oregon, sometime after William's death, where she died at age 86. (Note: This writer was unable to find documentary evidence of Bell's marriage to Lucy. Absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence).

Slow But Steady

Seattle's population in 1870 was just over 1,100, so the demand for new homes and other buildings was not great. Belltown had some topographic challenges as well. A large ravine ran from the waterfront inland on Bell's claim, and much of his property was located on the gradually descending north slope of Denny Hill. To the west, a steep bluff dropped from 2nd Avenue to the edge of Elliott Bay. Despite all, Bell anticipated the direction of the city's residential growth. In early 1877, the Puget Sound Dispatch opined:

"[A]s the value of lots forbid … residences near the wharves, men must either climb hills or go to the northward, as the south end of town will … be the location for foundries and shops of all kinds. At first every man who moved to Belltown was the subject of condolences. Now Belltown lots are in demand and the once dense forest is the site of new homes" ("Nearly One").

Growth was slow, but steady. By 1880, "Belltown had more than fifty houses and a grocery store. It also had at least two churches … The two-room Bell Town School, the first school north of Pine Street, was built at Third Avenue and Vine Street in 1876" ("Belltown Historic Context Statement ...").

Bell was generous. He donated land for a church and two blocks of his waterfront property for a barrel factory, which provided jobs for 85 men. More important, he made it possible for working-class families to own a home, selling lots for less than true value and accepting small payments.

Bell resumed his civic involvement and was elected to represent the Third Ward on the town council in 1876. He ran again in 1877 and 1878, but was trounced by his good friend and fellow founder, Arthur Denny.

By 1880 Seattle's population was barely over 3,200, but about to explode. By 1890, the census counted 42,837 Seattleites. Some of this growth came early, and William Bell was able to capitalize on it. His crowning, and final, achievement was the mansard-roofed Bell's Hotel (soon renamed the Bellevue Hotel) on the corner of Front (now First Avenue) and Battery streets, built at a cost of more than $30,000 and finished in 1884.

Bell started showing signs of dementia in the early 1880s. He began having "epileptic fits" ("Weary of Life"), which one Seattle newspaper uncharitably and inaccurately attributed to "over-eating" ("Passing Away"). Bell eventually became "totally demented" ("Weary of Life") and died on September 6, 1887, having been housebound for several years, his affairs managed by a guardian. In his will, he left specific properties to Lucy Bell and an organ to his stepdaughter, Leola. The rest of his estate was to be distributed equally among his surviving children – Laura, Olivia, Virginia, and Austin. But more family tragedy was soon to come.

The Last Bell

The immediate family of William Bell had suffered no deaths since that of Albina in 1857. Thirty years later and only about two months after William died, his oldest daughter, Laura Keziah Coffman, died in Seattle, age 44. In March 1889 Olive's husband, Joseph A. Stewart, died of typhoid in Florida. The male line of the Bell family would end that same year with the death of Austin Americus Bell.

Austin Bell and his wife, the former Eva Davis (1863-1899), had married in Vacaville, California, in 1883. Austin suffered from serious intestinal health problems of long standing, but was an astute businessman and rapidly increased the value of his inheritance. In early 1889 he was making plans for a signature building on Front Street next to his father's hotel (by then called the Bellevue Hotel). With no forewarning, at 10:30 a.m. on April 28, 1889, he went to his office, locked the door, and shot himself in the right temple with a 38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver. An affectionate note to his wife explained that a lifetime of poor health was made unbearable by the fear that he was suffering from the same dementia that had doomed his father. Austin Bell, at the age of 35, simply decided that life was not worth living. His marriage had produced no children.

As a memorial to her husband, Eva hired Elmer H. Fisher (1844-1905), a prominent Seattle architect, to design the building her late husband had envisioned. The Austin A. Bell Building was completed in 1890, and in 1974 was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Where They Rest

The remains of Bell's first wife, Sarah, and daughter Albina were brought from California in 1889 and buried in the family plot in the Oddfellows section of Seattle's Mount Pleasant Cemetery. In the center of the plot a short, square, stepped granite pillar, greatly eroded by the passage of time, bears the names of William, Sarah, and Albina. The name etched on the fourth side is no longer discernible, and three smaller tombstones bear no trace of who might lie beneath. A flat bronze plate marks the graves of Virginia Bell Hall and her daughter, Olive Hall Banks. The grave of the oldest Bell daughter, Laura, is located in another part of the cemetery. Austin Bell's grave is in the city's Lakeview Cemetery on Capitol Hill.

Four years after Bell's death, historian Frederic Grant wrote of him:

"[H]e was honest and honorable in every relation in life and highly respected by all who knew him. His name will always be associated with the founding of Seattle … He was a man of the most exemplary life, of a naturally confiding and kindly disposition and a loving and tender husband and father" (Grant, 401).