On September 25, 1858, with his half-brother Qualchan and Qualchan’s wife Whistalks, Yakama warrior Lokout rides into the camp of Col. George Wright. The three relatives are answering a summons amid the Plateau War to meet with Wright and discuss terms for peace. The camp of Wright’s 700 troops and dragoons lies along the shore of Ned-Whauld or Latah Creek, which will be renamed Hangman Creek after their encounter. At the camp the brothers learn that their father, Owhi, is being held captive there. Qualchan has become so notorious a warrior that within 15 minutes of his arrival he is identified, seized, and hanged. Lokout and Whistalks escape.

A First Life

The best accounts of the life of Lokout (1834-1913) come from Theodore Winthrop (1828-1861), Andrew Jackson Splawn (1858-1947), and Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952). All three met him. Winthrop hired Lokout as a guide in 1853 to help him across Naches Pass, a story that Winthrop told in his 1861 memoir The Canoe and the Saddle, published posthumously after Winthrop died as a Union officer during the Civil War. Yakima rancher and state senator Splawn met Lokout in 1906 while conducting interviews for his 1917 biography of Kamiakin (1800-1877), who had been the influential leader of the Yakama Tribe of Indians. The best record of Lokout’s distinguished but overlooked life was made by photographer Edward Curtis or his field assistants.

Historians still debate exactly how Qualchan (d. 1858) came to be so hoodwinked that day in 1858 and the roles his kinsfolk played. Col. George Wright (1803-1865) must have believed that Lokout bore no importance to his plan to avenge Col. Edward Steptoe (1815-1865), whom the natives had embarrassed and defeated in a battle on May 17 that year. Wright did not know that Lokout had fought in that battle. "When Col. Steptoe was defeated in 1858," Splawn wrote, "Lokout was one of the Indian sharpshooters selected by Ka-mi-akin to pick off Captain O. H. P. Taylor and Lieutenant William Gaston, saying, 'These two men must die if we are to win,' after which these officers were special targets of the unerring rifles. Thus fell two gallant men, victims of an ill-advised expedition" (Splawn, 126). Wright and his men never recognized Lokout as a sharpshooter or he would have been hanged. A native in Wright’s camp likely lied to protect Lokout’s identity and thus secure his release. Their father Owhi later was shot trying to escape – one of many casualties of Col. Wright’s scorched-earth campaign against the tribes.

Lokout was an observer, if not an actual combatant, as Wright stormed through Eastern Washington, killing people of many tribes besides the Yakama and Spokane, 16 by hanging, many more than that by rifle fire. Wright’s men torched storehouses of roots and grains, destroyed crucial crops the people had planted to last the year, and burnt down their winter shelters. He ordered his troops to round up a herd of more than 700 horses and shoot them, while their owners watched from hills nearby. The slaughter took two days. The site of that atrocity, near Liberty Lake, came to be named Horse Slaughter Camp and is commemorated by a stone marker and inscription. Wright told his men, "Kill them all," the title of a 2016 biography by Donald L. Cutler.

Following their ordeal on the shore of what would be called Hangman Creek, Lokout and Whistalks (1838-1909) fled to Montana for their safety. Lokout would outlive Wright by 48 years and claimed he participated in the battle of Little Big Horn. Lokout also claimed he had experienced a vision, or consummated a wish, that Wright would meet an early death. In a shipwreck north of San Francisco, Wright and his wife died in 1865, their battered remains discovered two months later. Lokout and Whistalks, meanwhile, made their home at the confluence of the Spokane and Columbia rivers for the rest of her 71 years, living at peace and feeding on salmon.

A Second Life

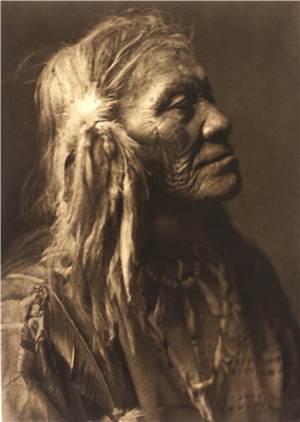

From 1907 to 1930, Seattle photographer Curtis released 20 volumes of The North American Indian, a project that comprises 1,500 photographs of American Indian tribes across the United States. In the seventh volume of that collection is a portrait of one Luqaiot, identified there as a son of a Kittitas chief. That tribe or band occupied the Kittitas Valley and present-day Ellensburg. Research reveals that the 1910 Curtis field photo in fact immortalizes the same man Splawn knew as Lokout. After his close scrape with Col. Wright, Lokout would join his mother’s Spokane Tribe. His wife Whistalks also hailed from the Spokane Tribe, further ensuring Lokout’s membership.

Qualchan, unlike Lokout, is familiar to Spokane-area residents. The name of the Yakama chieftain who died in 1858 has been appropriated for a golf course, a housing development, and a foot race. What is less known is that both brothers were guerilla fighters. Their tactics included night raids and horse rustling, grass fires, and scalping. Those brothers became partners in "one of the greatest federations of Indian tribes ever recorded in history" (Splawn, 87). Lokout’s life in many ways is more inspiring than his unlucky brother’s for his capacity to keep a level head and to overcome outsized odds.

In 1856, Lokout was fighting against Washington Gov. Isaac Stevens (1818-1862) after a second Walla Walla treaty meeting. Stevens had slighted local tribes by coercing them to sign away their traditional lands. The Nez Perce and Yakama were firing at full gallop, the less-seasoned white troops dismounting to take aim. The cover was scrubby and sparse. Qualchan, leading the charge, ordered his people to set the cover burning and keep on fighting after dark. At age 22, Lokout was already practiced as a tracker, sharpshooter, and guide. But that battle on September 19, 1856, almost did him in.

According to numerous accounts, Lokout sustained two shots to his chest but fought on. He killed one trooper in hand-to-hand combat before he passed out from fatigue and pain and toppled to the prairie floor. Night fell and the skirmishing continued. Grass fires set by his tribesmen smoked and flamed. A passing military volunteer spotted Lokout on the ground and swung near enough to smash him in the forehead with his gun butt, caving in his skull. Militiamen delivered such strikes to save lead when they ran low, intending them as surefire death blows. The hardy Yakama warrior did not die, though. Lokout healed from the crushed forehead and lived until 1913. "His skull had a hole in it that would hold an egg," wrote Splawn, who found Lokout trustworthy in 1906. Photographic evidence from Lokout’s adoptive Spokane Tribe confirms the astounding gouge. Four years after Splawn met the disfigured Lokout, Curtis and his staff visited to get information for the volume on The North American Indian covering the Yakama of Washington and the Kootenai of Idaho.

How Curtis heard about Lokout is impossible to say, but Qualchan’s mutilated half-brother agreed to be interviewed and to give his photo at a formal sitting. The photo shows the former Yakama warrior in aristocratic profile, his face lined, his chin nobly raised. The necklace, feathers, and long hair in the photo contradict his 76 years of age. The entire photo is tinted gold in the signature Curtis orotone, or "Curt-tone." What is remarkable about that photo, though, is less what it shows than what it hides – the brow gouge, the forehead furrow that remained as a memento of the Plateau War of 1855-58, often called the Yakama War. Using a forehead combover, Curtis styled Lokout’s hair to hide the gouge. Perhaps he considered the wound too unsettling to behold, too graphic a record of non-Native invaders and the wreckage they had wrought. Some ethnologists and historians fault Curtis for altering his photographs. They say he portrayed his Indian subjects in stereotypical ways, typifying them as a vanishing race that was unable to endure the modernist onslaught. Others say he made noble savages of them. In one photo Curtis removed a clock that blighted a teepee scene. He also always turned his camera away from the cars that hauled his gear, the squalor some tribes had to live amid, and from the factory clothing the Indians preferred to wear.

Tribal photos show Lokout dressed like other twentieth-century Indians in blankets, leggings, hair braids, and a cowboy hat with rattlesnake-skin band. Curtis hauled quaint regalia to adorn his photo subjects and to suit them to stereotypes of the times. He likely hauled in the gear that adorns Lokout in the photo – the necklace and feathers a kind of costumery for character actors on a stage. Lokout probably earned a dollar from Curtis by agreeing to sit for the shot, the standard rate the photographer paid. Collectors today are willing to pay far more than Curtis could have ever guessed. A 15-by-19-inch photogravure titled Luqaiot–Kittitas, sold at auction in Scottsdale, Arizona, for $1,287 in 2022.

A Third Life

If no one before now connected Lokout and his sibling Qualchan with the Curtis photo, that’s because Curtis spelled the names "Luqaiot" and "Qahlchun." Field linguists often transcribed Indian names phonetically or relied on erratic sources. To muddle the nomenclature further, Lokout had several other names – Loolowcan, Laquoit, L’Quoit, Quo-to-we-not, Soka-tal-ko, and Rain Falling from a Passing Cloud. Some Indians took different names at different periods in their lives or gave false names to whites who might do them harm. Had Wright never learned the name of Lokout’s ill-fated brother, Qualchan might have lived as long a life as Lokout did. By the time Curtis encountered Lokout, the aged warrior was the only Indian survivor of that dark day. In the long interview Curtis conducted to accompany his photograph, Lokout shared 17 pages of his recollections, including that deadly morning on Hangman Creek.

Due to the surface charm of the photo Curtis took of Lokout, it gained a separate life. Long after its publication by Curtis, it came to be altered and colorized then bundled as a trading card with chewing gum and sold by a Boston company in 1947. We might call that rendition an appropriation of an appropriation, a kind of caricature. The tilt of the chin becomes defiant or pugnacious. The forehead is laid bare, contrasting Curtis's thoughtful combover. It shows no sign of a wounding, because of course Curtis himself had concealed it. That image made miniature, packaged with chewing gum, perpetuated a common agenda that made out the Natives to be stalwart stoics whom the reservation system and the Bureau of Indian Affairs served well. The text accompanying the card likewise makes out the Natives to be the cause of the Plateau War. Lokout "was drawn into the Indian uprising by the act of his brother, in killing some prospectors."

In the trading card still available for sale to collectors today, no mention is made of Wright’s rampage that killed so many indigenous people and horses in 1858, nor does it allude to Qualchan’s execution. Lokout is identified – like Curtis had done in his quick trip through tribal lands – as a member of the Kittitas Tribe. The seat of Kittitas County is Ellensburg today. The Kittitas people were in fact a band within the Yakama Tribe, the same tribe whose name was to be identified for more than a century with the war they were wrongly credited with starting and prosecuting. The Goudey Gum Company packaged Lokout’s card in a series it dubbed Indian Gum.