On January 19, 1905, a granite statue of Governor John Rankin Rogers is dedicated on the lawn of Capitol Park (later Sylvester Park) in Olympia, directly across from the state capitol building. It has taken more than a year to raise funds to build the memorial, and its arrival is eagerly awaited in the capital. But the sculpture is so heavy that the delivery boat is unable to dock when it arrives in the city, and it goes downhill from there. Once the public sees the statue, many complain that it's not a good likeness of Rogers, and at the dedication ceremony – held in a steady rain for nearly the entire affair – a key word in its inscription is found to be misspelled. The offending noun is soon chiseled out, but the rest of the message remains.

Pennies and Nickels

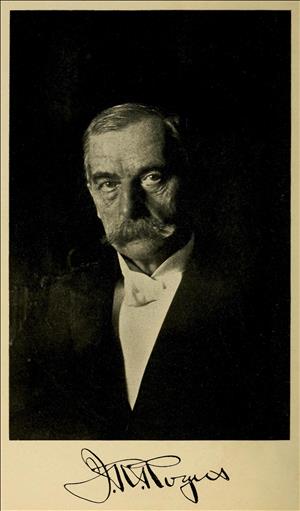

John Rankin Rogers (1838-1901), Washington's only Populist governor, served as the state's third executive from 1897 to 1901. Though his eloquent oratory for social and economic change alarmed more than a few when he first ran in the depression-ridden year of 1896, he proved to be a capable and prudent administrator. He gained the respect of much of his constituency and was reelected as a Democrat in 1900. But he died unexpectedly from pneumonia in December 1901.

There were various suggestions for a memorial to the governor, but it was the schoolteachers of Puyallup (Rogers's home prior to his election, and where he planned to retire) who acted. School principal J. M. Lahue presented a proposal to the Teacher's Institute of Pierce County, which accepted it and named a committee of nine prominent men from across the state to handle fundraising and the arrangements for construction of the monument. In part, funds were raised from donations of pennies and nickels from schoolchildren, which might explain why it took more than a year to raise the money needed. By the autumn of 1904 between $2,500 and $3,000 had been collected, which was sufficient to cover the $2,500 cost of the memorial plus ancillary expenses.

In November, Alden Blethen (1845-1915), a member of the statue committee and editor of The Seattle Times, published an editorial with a short elegy to Rogers. The paper explained that the epitaph would be inscribed on the memorial and invited public comment. One reader complained about the word "plebeian" in a phrase that described Rogers as a "Plebeian, Philosopher and Statesman" ("The Rogers Monument"), but the Times defended the decision in a subsequent editorial on December 1. At some length, the paper explained that the term was not meant to be contemptuous but instead was an acknowledgment of Rogers's work and dedication during his life to help the "common people" ("The Rogers Monument").

The committee consulted with Rogers's wife, Sarah (1840-1909), and her daughter, Carolyn Blackman (1870-1961), on where to place the memorial, and they chose a site in Capitol Park that was directly in front of the recently reopened capitol building. (Another option would have put it in the northeastern corner of the park.) The New England Granite and Marble Company from Seattle was selected to create and install the monument, and work began on its foundation in December. The statue itself was finished by this time and, along with its base, was shipped in pieces by steamer from Seattle to Olympia. However, the parts were so heavy that the boat could not dock when it arrived. They had to be transferred to a barge and towed to shore before being taken to the park for assembly.

Snags and Surprises

The John Rankin Rogers statue was installed on January 6, 1905, the same day that Olympia's Morning Olympian published a front-page story alleging that there was an error in the memorial's message. Titled "Col. (Alden) Blethen Was Wrong," the article asserted that a key phrase in the inscription was incorrect, specifically one that described Rogers as the "Author of the Barefoot Schoolboy Law." The account said that a nearly identical bill had been drafted by an unnamed but "prominent public man" ("Col. Blethen…") in 1892 and sponsored in the 1893 legislative session by House member J. E. Tucker (1833-1910), an attorney from Friday Harbor. The paper added that the bill passed the House by a 58 to 11 vote but lost on a tie vote in the Senate.

The story gained little traction, but another problem arose when the 15-foot-tall monument was erected later that day. Passersby inspecting the statue complained that it did not look like Rogers. "Comment on the finished work was varied, but mostly unfavorable," explained Seattle's Post-Intelligencer the following day. The sculptor – identified by the paper only as "a Mr. Field, of British Columbia" – was said to have failed to accurately depict not only Rogers's face but also his figure and pose. Even the statue's pedestal and its location did not escape criticism. The Morning Olympian subsequently excoriated the memorial in an editorial after its dedication, writing, "as a work of art it is atrocious," and further criticizing its material: "The rock is a peculiar, speckled granite, the specks making the finer lines of the face appear anything but pleasing. It is not Governor Rogers and no stretch of the imagination can conjure up Governor Rogers from its lines" ("The Rogers Monument").

After its installation, the statue was covered with a canvas veil and awaited its formal unveiling. The dedication ceremony was held on the afternoon of January 19, and despite a steady rain that continued for nearly the entire event, a crowd of 2,000 to 2,500 attended and listened patiently through four speeches from the some of the state's foremost political figures. A sudden heavy shower forced Tacoma Mayor George Wright to cut his short, but Governor Albert Mead (1861-1913) was more fortunate when he gave the final, and longest, speech of the day. He praised Rogers and pointed out how the departed governor had resolved the dichotomy between his forceful calls for change when first campaigning compared to his more conservative acts once elected: "Some of us seem to lose sight of the fact that partisan and patriot are reconcilable, and yet in the life of such a man as John R. Rogers we have an example of the two commingled" ("All Praise Gov. Rogers").

As Mead finished, the rain almost miraculously paused and, for just a moment, the sun came out and shone on the monument. Twelve-year-old John Edwin Rogers (1892-1995), grandson of the late governor, untied the cords holding the covering in place, allowing it to drop and the statue to be revealed. After a brief benediction, the crowd inspected the memorial. It didn't take long for someone to point out that the word "plebeian" in the inscription was misspelled. The statue committee was so furious that it refused to pay the New England Granite and Marble Company until one of its employees came to Olympia nearly two weeks later and chiseled out the error.

The word-sized blank rectangle remains in the inscription today, but it's one of those things that attracts little attention unless you're looking for it. Most readers focus instead on the entire message, and its final sentence, which appears on the base below the statue itself and contains a quote from Rogers that summarizes his philosophy: "I would make it impossible for the covetous and avaricious to utterly impoverish the poor. The rich can take care of themselves" ("The Rogers Monument"). On the opposite side of the pedestal is an engraving of a barefoot schoolboy, clad in knickers.