In February 1970, a group of young Vietnam war protestors found themselves in legal hot water when they were charged with inciting a riot through the streets of Seattle. According to Kit Bakke, who wrote a book on the so-called Seattle Seven, "Their energetic but quarrelsome efforts to stop the war and remake their world had hardly gotten off the ground when Michael Abeles, Jeff Dowd, Joe Kelly, Michael Lerner, Roger Lippman, Chip Marshall and Susan Stern were targeted by a federal grand jury and indicted and arrested on conspiracy and riot charges. The trial of the Seattle 7 showcased their naiveté, wit and unexpected savvy as they resisted their government’s determination to quash dissent against racism, capitalism and the war" (Seattle Times, May 3, 2018). In this first-person account written by defendant Roger Lippman, he revisits the trial and its aftermath. As Lippman writes, "In December 1970, U.S. District Court Judge George Boldt charged the seven Seattle Conspiracy defendants on trial in his Tacoma courtroom with contempt of court. We were being prosecuted for inciting one of the largest and angriest Vietnam War protests in Seattle to date. The most prominent local trial of antiwar activists had featured vocal defendants, audience participation, and a star government witness who admitted he was lying. And finally, with the prosecution's case in a shambles, the trial broke up amid bitter denunciations and a full-scale riot in the courtroom."

The Seattle Seven Conspiracy Trial, by Roger Lippman

The Vietnam War was at its peak of horror, with mounting casualties on both sides and the U.S. considering the use of nuclear weapons. President Nixon was directing the bombing of much of Indochina and attempting to suppress the resulting domestic protests. The unpopularity of the war had forced the retirement of his predecessor, Lyndon Johnson.

I had quit college in 1968 to join many others in working full time against the war, which was more important to me than pursuing a degree in chemistry. Within a year I was a leader of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in Seattle. And 20 years ago I landed in Federal prison for my part in the regional successor to the trial of the Chicago Conspiracy.

When Nixon took office, his Justice Department intensified the counter-attack on the antiwar movement (begun by Johnson's Attorney General Ramsey Clark with the indictment of Dr. Benjamin Spock and others), indicting eight prominent activists in Chicago for conspiring to organize protest demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. As the Chicago Conspiracy Trial unfolded in late 1969 and early 1970, the nation watched with mounting outrage as Judge Julius Hoffman trampled on the defendants' rights. Toward the end of the trial, word circulated that there would be massive protest demonstrations across the U.S. the day after the end of the trial if the Chicago defendants went to jail. As the police and the courts suppressed conventional protests, there seemed to be less of an avenue for peaceful dissent, and antiwar activities took on an increasingly militant tone.

And thus was born The Day After (TDA), the next in a series of national campaigns against the war and the repression of the opposition. When the Chicago case went to the jury, Judge Hoffman jailed all the defendants for contempt of court before the jury had even reached a verdict, and TDA was on. Over the next two days, thousands of opponents of the jailings and the war took to the streets nationwide.

The Seattle Liberation Front (SLF), then the city's leading antiwar organization, issued a call to shut down the Federal Courthouse. Dozens were arrested on February 17 as more than 2,000 demonstrators attacked the courthouse and the Federal Office Building with rocks, bottles, and paint, and battled police in the downtown streets. Tear gas drifted into a courthouse elevator just as the door was closing to take a prosecutor upstairs. The newspapers reported that a demonstrator threw a grenade at the building.

I wish I had been there, but earlier in the month I had moved to San Francisco to become the editor of a radical newspaper, and also to deal with the consequences of refusing induction into the army. I did manage to participate in TDA in Berkeley. As attorney Michael Tigar said subsequently in court in Tacoma, "If Roger Lippman threw a rock at a Seattle police officer on February 17, 1970, he should be hired immediately by a major league baseball team, because it was the longest throw in history."

Expressions of antiwar feeling continued apace, as did repression by police and the courts. Throughout the spring the country was wracked by angry, militant demonstrations against the war in Vietnam, the invasion of Cambodia, and the killings of students at Kent State and Jackson State by National Guard troops and police. The movement was determined to raise the price of the war until it became unacceptable to the government. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had warned LBJ that the country could become ungovernable if he tried to send a million soldiers to fight in Vietnam. Now, with half that many in the field, the price was becoming measurable. Budding scientists like me dropped out of school to riot in the streets. Police departments had trouble recruiting officers. Glass broke.

There was massive alienation from established institutions, and domestic tranquility was disintegrating. So much for One Nation Under God. Now it was Reefers, Rioting, and Revolution.

Indicted in Seattle

On April 16, 1970, a Federal Grand Jury in Seattle indicted eight people, myself included, for conspiracy to cause damage to Federal property at TDA. Not for causing damage – none of those arrested at the demonstration was indicted – but for organizing others to do damage. I was arrested in Berkeley, and when I got out of jail the next month and returned to Seattle, I was pleased to see "Free Roger Lippman" scrawled on the wall of the Century Tavern, a prime hangout for SLF members. Another of the eight was not apprehended, and we thus became known as the Seattle Seven.

The Seattle conspiracy indictment charged me with attending exactly two meetings, and nothing else. Many of the acts attributed to the other defendants were of a similar character – attending meetings and making statements. Every one of the overt acts of conspiracy itemized in the indictment took place in public, most of them with several hundred people present, not exactly the secret plot implied by the charge of conspiracy.

Conspiracy: "That elastic, sprawling and pervasive offense ... so vague that it almost defies definition" – Former Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson

While some of the defendants actively organized TDA, several of them didn't like or didn't even know each other. This conspiracy existed primarily in the minds of the U.S. Department of Justice. Chip Marshall, Jeff Dowd, Mike Abeles, and Joe Kelly were recent transplants from SDS in Ithaca, New York, but Kelly didn't move to Seattle until after TDA. I first met Abeles after the indictment. Susan Stern, who had been an activist in Seattle for several years, had differences with most of the defendants, as did I. Mike Lerner was a visiting professor of philosophy at the University of Washington. As far as I could tell none of the other defendants got along with him.

The indictment was brought at the behest of U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell, the future Watergate conspirator, and Guy Goodwin, his special assistant for political prosecutions. It was a continuation of Nixon's Chicago strategy, which was to blame protest leaders for the national chaos caused by the war in Vietnam, as well as to tie up leading organizers and get us off the streets. Some were selected to make us look like a dangerous group containing a wide variety of radical affiliations. And for this distinction, according to my FBI file, I was awarded the FBI's highest rating, Security Index-Level 1, which meant that my activities were under continuous surveillance. (Or, it was supposed to mean that, though my FBI file gives little evidence of such enhanced snooping.)

On Trial in Tacoma

As the trial approached, we got a glimpse of the overactive imaginations of the FBI and the Justice Department. In one pre-trial session, when prosecutors were displaying the physical evidence that would be introduced against us, they announced that they would show us the "grenade" that had been thrown at the courthouse. With great fanfare a squad of FBI agents gingerly brought in a box. The assembled defense staff practically collapsed in laughter when they saw that it was a real grenade, all right – hollowed out, with an alligator clip attached to the end to form a roach clip, and a roach still in its teeth. Probably someone's souvenir of Vietnam.

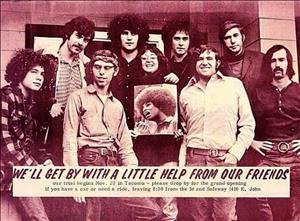

Mobilized by a dedicated defense organization of some two dozen volunteers, large numbers of antiwar activists took up the defense of the Seattle Seven. The judge, recognizing the extent of our public support, moved the trial from Seattle to Tacoma to try to get away from our base. Nevertheless, as the trial proceeded, the courtroom was often filled to capacity with spectators expressing political support for the defendants.

Jury selection began Thanksgiving week of 1970, and those sympathizers played a significant role in the proceedings. The jury pool was composed largely of rural Southwest Washingtonians. Those who let on that they had given any thought to the nature of the Vietnam War were dismissed by the prosecution, to a rising crescendo of objection from the defendants and our supporters. Tension increased, and the court began to reduce the number of spectators allowed in the courtroom, as well as compelling those seeking admission to wait in line outside for long periods in the chilly rain.

Just as we took the trial out to the community and brought the community to the trial, we brought our politics to the trial. Our decision to have two of the defendants represent themselves gave us more latitude to express the political issues at hand to the court. While the jury appeared conservative and uninformed, we gambled that our best bet was to try to explain to them the political realities that led to our presence in that courtroom.

The prosecution began its case the following week. At each opportunity we attempted to raise the political issues behind the charges: the Vietnam War and the use of the courts to repress the opposition. Predictably, Judge Boldt cut us off each time. We also tangled with him over the admission of spectators and our wish to speak directly to the jury. The judge, an elderly conservative, had learned some lessons from the inept handling of the Chicago Conspiracy trial by Judge Hoffman. But as we settled into an uneasy tension with him in struggling to assert our politics as part of our defense, it became increasingly clear that he was out of his depth in dealing with vocal defendants who insisted on going beyond the narrow legal issues.

Judge Boldt (as defendant Jeff Dowd was attempting to make a statement): Dowd's not a member of the Bar.

Voice from the audience: He's a member of the Century Tavern.

As the days dragged on we began to pick up feelings of sympathy from jurors. Some of the defendants passed the days leaning back, legs crossed, with toothpicks between their teeth. One day a juror in the front row took a couple of toothpicks from his jacket pocket and handed one to another juror behind him. In unison the two leaned back, crossed their legs, stuck the toothpicks in their mouths, and gave the defendants a wink.

Things heated up when the government produced its star witness, Horace "Red" Parker. He had joined the antiwar movement but remained a peripheral figure. Most activists who knew Parker did not particularly trust him, but nevertheless there was shock in the courtroom that day when we learned that he had become a paid FBI informer.

Over the next several days of testimony, Parker spun a remarkable tale of efforts to ingratiate himself with activists by supplying drugs, explosives, spray paint, and firearms training. He attempted to implicate several of the defendants in a variety of illegal activities, though much of his testimony missed the mark, referring to people who were not charged or to events that took place after TDA. He conceded that he knew only two of the defendants, Susan Stern and me. Parker claimed that he had gone to the FBI after becoming disturbed about the violence of some antiwar activities. But there were some who believed that his change of heart had come after he was arrested in a demonstration and, facing jail time, decided to make a deal with the police.

The Government's Case Collapses

Finally, under cross-examination by defendant Chip Marshall, who was acting as his own attorney, Parker admitted to being less than honest. Marshall's withering questioning of the witness concluded with the following remarkable exchange:

Marshall: Did you recruit others into violent acts?

Parker: The answer would have to be yes.

Marshall: While with the FBI, have you ever encouraged anyone to violate a law?

Parker: Yes.

Marshall: You feel very strongly that we are bad people and should be brought to justice?

Parker: That's one way of putting it.

Marshall: So you would go to almost any length of trickery to bring us to justice?

Parker: Yes, any length.

Marshall: Are you willing to lie to get us?

Parker: Yes.

Marshall (turning to the jury): That’s what he said.

Parker and his credibility were finished, and the government's case was thrown into paralysis. With the prosecution embarrassed and unprepared to produce another witness, the proceedings stumbled. Meanwhile, the defendants continued to resist the exclusion of more and more spectators from the shrinking courtroom.

Defendant Chip Marshall to the judge: You have done the same thing that good Germans do.

Judge Boldt: I'm not a German, you understand that, my ancestors are Danes.

Defendant Susan Stern: There's something rotten in Denmark.

Judge Boldt: For once I have to agree with you, Mrs. Stern. I was there about a year ago and I know.

Mistrial

Tensions reached the flash point the next day, Thursday, December 10. Incensed that our supporters were still being forced to wait outside in the increasingly wintry weather, and that Judge Boldt had not yet held a hearing on the spectator issue, we refused to come to the courtroom that morning unless the judge would agree to a discussion. From a defense meeting room down the hall we conveyed our demand via our attorneys. Word shortly came back from court that the judge insisted on our presence, and we concluded that he meant business. We also heard that the jury was seated in the box, which had never happened before until all parties were ready to proceed. It seemed clear to us that the judge's intent was to turn the jury against us by carrying on this confrontation in its presence.

So we gathered our papers and prepared to head to court. As we opened the door to the hallway, there, to our surprise, was the judge himself, who had come to order us to court personally. But we were already on our way, and we ran down the hall to get there before him. With a 20-second advantage over the judge, Chip Marshall calmly explained to the jury our dispute with the judge over admission of spectators. When the judge arrived in the courtroom, he exploded. He dismissed the jury, declared a mistrial "because the defendants have seriously prejudiced themselves," and found us in contempt of court. (Except for Susan Stern, who was absent from court that day due to illness.)

The government had no case left, and the jury was likely to let us off. The only way out was to use our conduct as an excuse to end their embarrassing dilemma. They would claim that we had prejudiced the jury against ourselves and send us to jail for that. A trap was set, and we walked into it.

The judge then recessed court for the weekend, announcing that he would pray for "divine guidance" on how to deal with us. Meanwhile, jurors interviewed by the media emphasized that they were still impartial.

On Monday Judge Boldt gave us each a chance to speak before sentencing. We tore up the contempt citations. Mike Abeles and Chip Marshall threw a Nazi flag at the judge's bench, saying, "That's the flag that ought to be up there next to you!" Then Susan Stern, though not charged with contempt, began speaking in solidarity with the rest of us. Boldt told her not to, but she proceeded anyway. Though barely able to stand because she was recovering from an operation, she made a powerful statement in support of her co-defendants.

"Stop this diatribe!" the judge finally shouted, and 20 U.S. Marshals armed with clubs burst into the room. One grabbed Stern from behind, and as Mike Abeles jumped on the marshal's back, most of the defendants, our lawyers, and our supporters in the courtroom sprang to her defense. Judge Boldt, proclaiming that his prayers for guidance had been divinely answered, sentenced each of us to six months in jail for contempt, banged his gavel, and fled the courtroom. Defense attorney Michael Tigar was maced in the face while attempting to protect Stern. In the ensuing Us vs. Them melee, more of Them ended up with bloody noses, but it was Us who ended up in jail.

After Michael Tigar was maced in court by U.S. Marshals, a supporter wiped his eyes with a damp rag. Asked how he felt, Tigar responded, "I can see things much more clearly now."

Returning to court afterward, this time in custody, we were charged with a second count of contempt for the courtroom free-for-all, sentenced to another six months, and packed off to the Tacoma City Jail without appeal bond.

Jail

Ever since the Seattle Conspiracy indictment, which had been announced personally by John Mitchell and J. Edgar Hoover, the prosecution had made a point of emphasizing how dangerous a group we were – that just by getting together we had been able to turn peaceful protest into violence. Ironically, they made us stronger as a group than we could have been without their help.

In their hysteria, the prosecutors ordered us separated in jail. As a result we met the entire prisoner population, and we had contact with each other through our attorneys. While our supporters on the outside held a demonstration at the jail demanding bail for us and improved conditions for all prisoners in the jail, we organized the prisoners to participate from the inside. As the demonstration began outside, prisoners broke out the jail windows facing the street by throwing bars of soap. That drew applause from the demonstrators below, and when one picked up a paper airplane that had been floated out a broken window, he was arrested for illegally communicating with a prisoner.

The government pushed the irony to ever more ridiculous heights. Jailers came into the cellblocks and plucked out each Conspiracy defendant. They threw us in solitary confinement and took away all our clothes. By the end of the day we were dispatched in pairs to Federal prisons up and down the West Coast. Jeff Dowd and I went to McNeil Island, near Tacoma, and others went to Lompoc and Terminal Island, in Southern California. Now the dangerous radicals were in contact with the entire western Federal prison population.

People later asked me worriedly how we had been treated in prison, and I could tell them that Jeff and I received a hero's welcome from the prisoners at McNeil. They had been following the trial on TV news and the front pages of the newspapers for weeks, and they knew they would have the opportunity to meet us before long. They were impressed that we firmly stood up for our rights in the courtroom, and more than one person who had been sentenced to 25 years by Judge Boldt said, "I wish I'd done that!" Another prisoner, more cynical, told me, "They’re never gonna let you out of here."

Conclusion

A month later, after two trips to the U.S. Court of Appeals and more wrangling with Boldt, our attorneys finally got us out on bail. A year after the trial, the court ruled that Boldt, acting as both prosecutor and judge in a case in which he was emotionally involved, had unjustly sentenced us for contempt of court. Nevertheless, U.S. Attorney Stan Pitkin decided to re-file contempt charges, this time in front of a different judge. It was evident that a new trial could bring further contempt charges, so we came to a settlement. We pleaded no contest and received sentences ranging from one to five months.

Another year passed, and finally, in March 1973, the government quietly ended the case by dropping all charges. By this time the Vietnam War was winding down and Nixon's administration, particularly his Justice Department, was finding itself in deep trouble. They had gotten away with political prosecution, spying, illegal wiretapping, and burglaries against the opponents of the war. Now they had been caught doing most of the same things against the Democrats, which ultimately led to the Watergate downfall of Nixon and his top operatives.

By 1976, according to a notation in my FBI file, by then 1,000 pages long, I was "no longer a threat to the national security."

Where are They Now?

Roger Lippman finished his bachelor's degree and works in energy conservation. He formerly coordinated a project supporting solar energy development in Nicaragua. Chip Marshall worked in the Seattle area as vice president of a Los Angeles-based real estate development firm. He moved to Hong Kong to pursue new investment opportunities. Joe Kelly lives in the woods somewhere. Jeff Dowd helped found the Seattle Film Festival. He later worked in Los Angeles in the movie industry. Michael Abeles worked in Seattle as a ceramic tile installation contractor. He died August 24, 2016. Michael Lerner publishes a liberal magazine of Jewish issues in Berkeley. Susan Stern died in 1976. The eighth defendant, who remained underground until after the case was dismissed, is enjoying the obscurity that history has allowed him and will not be named here. Chief defense counsel Michael Tigar taught law at UCLA, the University of Texas, American University, and Duke, and remained active as a defense attorney in political cases. Tigar was interviewed about the Seattle trial on the Dick Cavett Show in 1970. U.S. Attorney Stan Pitkin died of cancer at age 44 in 1981. U.S. District Judge George Boldt temporarily left the bench in 1971 to head Nixon's wage control board. He died in 1984.