On November 27, 1901, Seattle Mayor Thomas J. Humes signs ordinances to repeal actions by the Seattle City Council that would have created 120-foot boulevards on the north and south sides of what became known as the Lake Washington Ship Canal. The routes along the canal shores, which also planned for rail lines and sewer improvements, would have stretched from Lake Union to Salmon Bay and were championed by councilmember William H. Murphy. But powerful Fremont and Green Lake property owners voiced fierce opposition, in part to protect their land, but also objecting to their specific districts footing the tax bill. The repeal comes less than two months after the North Shore and South Shore boulevards were approved by the council, and the ambitious plan becomes another on the list of major Seattle projects that were approved but never came to be.

Need for Major Roads

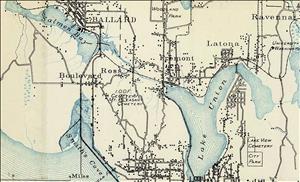

On September 23, 1901, Seattle City Councilmembers passed ordinances 7254 and 7255, which provided for the opening, widening, and extending of north- and south-shore boulevards along the Government Canal Right of Way. The boulevards were planned to each be 120 feet in width – significantly larger that the later developed Aurora Avenue North (90 feet wide) and nearly double the width of the Aurora Bridge (70 feet). This planning – and the fight against the boulevards – happened years before the Lake Washington Ship Canal's opening was celebrated on July 4, 1917 – exactly 63 years after Seattle pioneer Thomas Mercer (1813-1898) first proposed the idea of connecting the saltwater of Puget Sound to the freshwater of Lake Washington via Lake Union. The opening celebration brought 360,000 people to the Lake Washington Ship Canal and locks at Salmon Bay, which were first open in summer 1916 (and known after 1956 as the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks, or colloquially as the Ballard Locks).

Planning and initial work to create the Fremont Cut – above what’s now Nickerson Street and below what’s now N Northlake Way – had begun in 1883 when the Lake Washington Improvement Company contracted with the Wa Chong Company to provide immigrant Chinese labor to dig along the low-lying route of Lake Union’s outlet, Ross Creek, to Salmon Bay, according to the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society.

The South Shore Boulevard was to extend from Westlake Avenue west to Forney Street (now NW Bowdoin Place). The North Shore Boulevard was to extend from Fremont Avenue to the south boundary line of the Town of Ballard. The ordinances called for "the taking and damaging of landing and other property necessary therefor and for the ascertainment and payment of the just compensation to be made for the private property to be taken or damaged for said purpose and for an assessment upon the property benefited and for the purpose of making such compensation" (Ordinances).

At the same time, prominent University District residents asked the city council for a boulevard that would go from the University of Washington campus through what’s now the University District and on to Fremont, which would connect to the proposed boulevards on either side of the canal. The efforts gained support because of the need for sewer and water arteries to the north part of the city.

Councilman William H. Murphy, who was first elected in 1900, introduced the bills, 1577 and 1578, that led to the ordinances for the roads from Lake Union to Salmon Bay. The bills were referred to the council’s street committee. On September 30, 1901, the committee reported favorably to the council and that same Monday evening the bills received their second and third readings. The city council took action on October 1, the day the bills were delivered to Mayor Thomas J. Humes, and he signed them October 2.

A Question of Funding

The canal boulevards would be funded by newly created north- and south-shore improvement districts, which included Fremont and Green Lake. Property owners there would be levied the assessment for the entire improvement, which created the backlash. Property owners in Fremont and Green Lake, areas annexed into Seattle in 1891, objected to the two neighborhoods footing the bill when people across Seattle would benefit from the boulevards. No one questioned the importance of the undertaking and the "great good that might be derived therefrom," The Seattle Star reported. "On the contrary, the consensus of opinion is that it would be of much benefit to the city. The objection raised is that the entire levy is to be made against so small a district. A solution of the problem set forth by a number of persons is that a district be created including the entire city" ("Protest Against ...").

Property owners also were unhappy about the prospect of valuable property being gobbled up by eminent domain. The Star reported vigorous opposition to the plan, and that citizens of Green Lake and Fremont wanted an appeal. Murphy pointed to the public need – something that was of serious concern, and ultimately a factor in Ballard annexing into Seattle in 1907. "The boulevards will make it possible to property sewer the district," Murphy said on October 9, 1901. "This will be almost impossible without the improvement. Again, at present there is no district roadway connecting Fremont with Ballard. A circuitous course up and down hills is now necessary to be taken to communicate by roadway between two places" ("Protest Against ...").

Stone Wall

Corliss P. Stone (1838-1906), one of Seattle’s first city councilmembers in 1869 and Seattle’s third mayor, elected in 1892, owned and profited from huge swaths of land in Fremont and Wallingford. In 1884, Stone platted his first of several additions to the city: the Lake Union addition, including 160 acres. After the Seattle Lakeshore and Eastern Railway was built in 1887, real estate plats started along the line. Stone and William Ashworth (the namesake of Ashworth Avenue N) platted the 30-acre region of N 36th Street and Ashworth Avenue N, which Stone named the Edgewater addition after Chicago’s Edgewater Beach. Today that area is where Wallingford and Fremont meet. Stone then platted an extension to Edgewater and followed with another 20-acre addition that adjoined Lake Union. Stone is the only person in Seattle’s history to have streets named for his first and last names: Corliss Avenue N and Stone Way N, which forms an unofficial boundary between the Fremont and Wallingford neighborhoods.

Stone strongly opposed Murphy’s boulevard plan, saying, "the undertaking will mean an enormous expenditure, and it is levying too much against so small a district. As regards this great outlay of money for proper drainage and sewer purposes, I should think some less expensive plan could be devised by which the same results might be obtained" ("Protest Against ...").

Another large property owner, A. J. Goddard, also opposed the plan. He suggested a sewer might be better placed along Kilbourne Avenue – the east-west arterial named for Stone’s nephew, Edward Corliss Kilbourne (1856-1958), who purchased from his uncle 40 acres of what’s now Fremont, developed it, and also built an electric trolley to run from Seattle to Lake Union. (The former Kilbourne Avenue is N 35th Street today.) In 1891, the year Fremont and Green Lake were annexed, Kilbourne and future Seattle mayor William D. Wood (1858-1917) extended the trolley line from Fremont around the eastern shore of Green Lake to a terminus at the northwestern shore, near where the Bathhouse Theater was later built. It was also where both men were selling lots in what they advertised would be "Seattle’s choicest suburb."

Benjamin Franklin Day, another property owner who settled in Fremont in the mid-1880s and donated the land for the school in his name – the longest continually operating Seattle public school, since 1901 – also opposed the canal plan.

Property owners and influential businessmen promised to employ every means possible to repeal the ordinances for the North Shore and South Shore boulevards. They said the plan would mean an outlay of $100,000 for condemnation of property alone – roughly $3.6 million in 2024 dollars, adjusted for inflation – and an equal sum or more would be needed for the roadway and sewer improvements. They argued it was deliberate confiscation of roughly three quarters of the land in the district.

Councilmembers pushed the boulevards' visual appeal, and noted that property owners purchased their land on easy terms and could meet the tax requirements. They argued that the roads would mean no worth to people outside Ballard or the north end. Still, nearby property owners objected and started referring to the boulevards as the 240-foot roadways (combining the widths on the north and south shores). They continued to hammer the point that the sewage problem could be resolve in a much more cost-effective way without taking such wide land sections.

Change of Course

On October 21, 1901, a remonstrance was filed against the boulevards, and on November 4, council bills 1731 and 1732 were introduced to repeal the ordinances establishing the boulevards. The issue came to a head in city council chambers on November 22, 1901, when the street committee buckled to the strong pushback.

Opposition was led by the Fremont property owners, including Stone. Their reasons were hard for some of the street committee to fathom, echoed by The Seattle Times coverage, which called the effort to repeat the decision "one of the strangest suggestions that has come to the attention of the council. Far seeking men connected with the city cannot fathom it. They suggest that there is some political significant, yet they are unable to point it out" ("Create One ..."). Members of the council’s street committee seemed surprised by the opposition from Fremont land owners. An unnamed committee member objected to a Times reporter:

"It really appears as if the citizens there desired to lock the door to all improvements around the lake and then throw the key away. There is much in the canal boulevards that does not appear on the surface. To my mind they are the most important and vital improvements that could have been suggested. What are the people going to do when the canal is built? How are they going to cross the canal, where will be the arteries of traffic if the boulevards are to be done away with? The boulevards were planned 120 feet wide, yet by the time double track steam and electric railways are provided for along them, a wagon way along the edge of the canal and a driveway on the higher embankment, it will have eaten away the 120-foot strip and there will be no ground to spare. At the crossing and locks driveway space thereon will have to be provided requiring ample area. And, without the boulevards how are the people to pass and repass. It means a climb up hill and down, from one side to the other from Fremont to Ballard, Ballard to Fremont, and a number of grades in every direction. One thing is sure, unless the citizens are inclined to open the way by these improvements, inviting manufacturers around the lake, they will be driven elsewhere, and for years, decades of years, the lake district, which is now so inviting, will be bottled up" ("Create One ...").

The Times described the opposition of Fremont residents as falling like a wet blanket on the spirits "of those who have taken more than a passing pride and interest in the matter. It will be hard for the council to act itself against the wishes of the people there and proceed with the work unless the whole city takes the matter to heart and devises some other mode of payment than the usual district assessments. This seems to be the sticking point with the opponents of the boulevards" ("Create One ...").

The resolutions against the boulevards won. Ordinances 7449 and 7450, introduced as Council Bills 1731 and 1732, were passed by the full council on November 25, 1901. Mayor Humes signed the ordinances two days later. Major arterials the size of what was proposed were never built on the north and south shores of the canal and locks. Doing so would have significantly changed the structure of Seattle roadways.