On November 7, 1975, Garfield and Bishop Blanchet high schools face off for the Seattle Metro League football championship before a record-setting crowd of 12,951 at Memorial Stadium. Blanchet is the defending state champion. Garfield – a school facing possible closure a few years earlier – has matched Blanchet's 8-0 record despite modest preseason expectations. The game features several players who will go on to play for the University of Washington, including future Seattle mayor Bruce Harrell. The four-overtime thriller will be talked about nearly a half century later; the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and The Seattle Times will rank it as the greatest Washington high school football game of the twentieth century.

Prelude to a Thriller

Garfield High School opened in Seattle’s Central Area in 1920 and saw continued enrollment growth until its peak at 2,300 students in 1939. But by the late 1960s, news stories circulated about racial tension and violence at Garfield, and by 1970 enrollment had plummeted to less than 1,000. In 1971, with the school also dealing with poor academic results, the Seattle School District discussed closing the school permanently. Meanwhile, Garfield Principal Roscoe Bass championed his school, telling the district it needed only a few years to become one of Seattle’s finest. He was correct. By 1974, with enrollment around 1,050, the community coined the slogan "Garfield has turned the corner."

The year before the 1975 Metro football championship game, Garfield won its fourth state boys basketball title. Bass, who believed athletics was a way to develop future leaders, hired Al Roberts as football coach in 1973. Bass told students that football would help turn things around at the school, but Roberts faced an uphill battle. The Bulldogs hadn’t won a football league championship since 1959 and had a sub-.500 record in 1973, Roberts's first season. After Garfield went 3-5 in 1974, Roberts took sophomores Darrell Powell (the starting quarterback), his brother Kevin (the starting fullback), cornerback Anthony Lyndell Jones, and other returning players to Everett Memorial Stadium to watch Blanchet play Wenatchee in the Class 3A state semifinals. Blanchet – a Catholic high school opened in 1954 two blocks from Seattle’s Green Lake – had a defensive line averaging 209 pounds, allowed only 5.6 points per game, and was led by junior Joe Steele, named the state's best running back that year by the Washington Sportswriters Association.

"He took all the sophomores who were going to be juniors," Darrell Powell recalled of the Roberts-led trip to Everett. "About six of us. He had a VW bus, so how many he could stuff in there. We’re watching Blanchet because they’re coming into Metro the next year (from the KingCo Conference). We’re watching them play and they looked like a college team to me, so well organized. Their punt returns were immaculate. He said, 'You see how organized they are? That’s where we’re going to be next year. You see that discipline? When they have a punt return right, look at it. When they have a punt return left, look at it.' He said, 'because that’s who we’re going to meet in the Metro title game next year'" (Powell interview).

The 1975 Season

In a 1975 season preview, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer picked Garfield to finish third in the eight-team Metro League South Division, writing that progress was being made with its wishbone offense, but doubting the team with five returning offensive starters could reach the Metro championship. Blanchet, which had defeated Mount Tahoma 14-6 to win the 1974 state title game, returned seven offensive starters and seven defense starters (out of 11). Blanchet began the season atop the United Press International and Associated Press polls, stayed there during the season, and outscored its first four opponents 95-28.

Garfield also started 4-0, and on October 8, 1975 – roughly a month before the Metro title game – the Bulldogs reached No. 8 in the UPI rankings. Two weeks before the Metro championship, both the Bulldogs and Blanchet remained undefeated and it was certain they’d meet for the championship. "We don’t care that they’re ranked No. 1 – they haven’t run into a buzzsaw like us,” Darrell Powell recalled. "We know their names: (All-Metro lineman) Trip Rumberger, (Times defensive player of the year) Tom Eagle, (All-Metro cornerback and running back) Ken Gardner, Joe Steele – we’ve been knowing their names for a year. They don’t know us. We know about them. And so, here comes the game ... We’re both 8-0. The city is abuzz” (Powell interview).

The Scene

An overflow crowd showed up at Memorial Stadium. Fans packed along the edges of the end zones and concourses and even into the obstructed-view seats high in the grandstands. Garfield's middle linebacker and co-captain Bruce Harrell said he’d never felt an atmosphere quite like it. People who hadn’t come to a Garfield game in years came out that night; it felt like the whole inner-city was behind the Bulldogs, he said. Coming out of the locker room to the sellout crowd – still the largest crowd for a high school game in Seattle history – Harrell felt like he could run through a wall. "There was sort of an unspoken racial element to the game, too – that Garfield was an inner-city (school) and Blanchet was on the north end," Harrell said. "You looked on different sides of the stadium and there was sort of this – there were no racial, disparaging fights or comments made, there was nothing like that – if was more of a subtle kind of thing that here’s this inner-city school against the Blanchet boys and we’re on an equal footing now. And you look at the stands and you could sort of see the different racial composition as well" (Harrell interview).

The Game

Blanchet entered with a 25-game win streak over three seasons, and players later admitted they didn’t think it would be competitive, let alone, as Steele put it, "the pinnacle of a lot of our careers" (Steele interview).

Blanchet took the opening kickoff and scored first on a 26-yard Frank Vaculin pass to Steve Williams. In the second quarter, they extended the lead to 14-0 on Steele’s 3-yard scoring run. Some Garfield players were nervous, and it showed. "We went to the sideline and Al said, 'Wait a minute. Is anybody having fun?'" Darrell Powell recalled. "He said, 'If you’re not having fun, you shouldn’t play this game. This is about having fun!' Because we were tense, you know. And that kind of broke the ice. Everybody kind of settled down. He said, 'I need somebody to laugh!' And we laughed a little bit of nervous laugh. He said, 'This is fun time right now! Here’s where the game gets fun!'" (Powell interview).

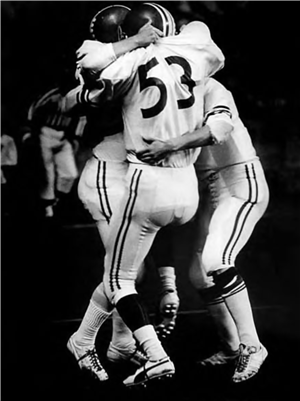

And it did. Garfield responded with Powell’s 27-yard touchdown pass to sophomore receiver Anthony Allen to narrow the margin to 14-7. The Bulldogs held hands in their huddle – something few teams did then. Four plays later, Jones intercepted a Blanchet pass. A 45-yard touchdown run by Garfield’s Teddy Martin tied the score at 14 with 8:22 left in regulation. Blanchet then drove to the Garfield 5-yard line but couldn’t score, and the championship went into overtime. Harrell, who had a game-high 16 tackles, said at that point it was anyone’s game and as intense as a high school game could get, in any city or state. Roberts was one of the best motivators around, Harrell said, and “had us as young kids believing in ourselves, doing things we didn’t think we can do" (Harrell interview).

The Overtimes

Given four plays to score from the 10-yard line in overtime, Garfield took the lead on Kevin Powell's 5-yard touchdown run. Blanchet answered on third down with Ken Gardner’s 8-yard run on a reverse.

Steele scored a second rushing touchdown in the second overtime, as did Martin for Garfield.

In the third overtime, Kevin Powell scored again, on an 8-yard run, and Steele answered with 5-yard touchdown reception from Vaculin.

The game – still the longest game in Metro League history at 2 hours, 55 minutes – went into a fourth overtime. Blanchet got the ball first, but Garfield dropped Steele for a 1-yard loss to force third-and-goal from the 11-yard line. That’s when Blanchet coach Mickey Naish called a play the team had never run. "You’ve gone through everything you’ve gone through in that game, and then it comes off the sideline that it’s a halfback pass," Steele recalled. "It’s just one of those things where you’re just going, "Okay, I think these guys know what they’re doing. And it was a hell of a call" (Steele interview).

"We would run this halfback pass after practice all the time, and it would just be Joe and I," receiver Steve Williams said. "No linemen, no quarterbacks, nothing like that. When the play came in and it was a halfback pass, I just kind of remember looking at Joe and thinking, 'Oh my God'" (Williams interview).

Steele got the pitch right and looked for Williams cutting across the end zone. Williams watched as Steele, who had a Garfield defender inches from his back, lobbed a pass off his back foot. Garfield safety Mervin Slade reached for the ball and was only inches away. "I was running across and I was looking and I can’t really see [Steele]," Williams said. "Then all of a sudden, I see him up on his tip toes. And he had this kind of funny delivery, a little bit like a pitcher throwing a fastball. And I caught the ball and never got touched. And the rest, as they say, was history" (Williams interview).

Garfield had one more chance to tie the score and send the game to a fifth overtime. An offsides penalty on Blanchet's extra point started the Bulldogs on the 15-yard-line instead of the 10. After two runs and an incomplete pass, Garfield faced fourth-and-goal from the 15. When Darrell Powell’s fourth-down pass went out of bounds wide right, Blanchet fans rushed the field. Post-Intelligencer Associate Sports Editor Royal Brougham presented the championship trophy for the 42-35 win. Naish, who was carried off on his players shoulders, told the newspaper it was "the most exciting football game I’ve ever coached."

The Aftermath

The loss for Garfield was devastating, Harrell said. "You’re very vulnerable at that age, too, very impressionable, and you wear your emotions right on your sleeve. And one can say, 'Well, it’s just a high school game.' But when you’re in high school that means everything to you" (Harrell interview). The only known video footage of the game is 8 mm film discovered by Blanchet alum Joe Wren. Though the footage is silent, the crowd’s reactions and sometimes shaky camerawork help the viewer imagine the intensity of the moment.

The following Friday, Roberts took the Powell brothers, Harrell, Jones and other Bulldogs to another meeting with their rivals – this time at a Blanchet pep assembly. Harrell told the student body he had no anger toward them, and that he wanted Blanchet to win its state quarterfinal against Sammamish. "They gave us a standing ovation," Darrell Powell said. "We felt like we had won" (Powell interview).

The bonds between coaches were unique. Roberts and Blanchet assistant coach Edd Olson were friends from their time as University of Washington students, and would talk often about teams they’d faced. The night before the Metro championship, the two coaching staffs met for pizza – a way to show their camaraderie. Neither coaches nor players can remember another experience like it, from the buildup to that pregame meeting, the four-overtime game, the pep rally and standing ovation afterward, or the friendships that endured over the following decades. "Whether you were the best kid on the team back in ’75, even for Blanchet also ... or last kid on the team, you always have that," Allen said. "And I’m sure everybody that played that night or suited up that night – and even most of the fans that went to the game that night – they’ll always have that" (Allen interview).

Blanchet lost its next game, a 23-20 upset against unranked Sammamish. Players said they were exhausted. Roberts went to watch Blanchet that next week and said they looked like a different team. He recalled thinking during the Metro championship overtimes that whoever won would lose the following week because no squad could recover in time from the physical and emotional drain.

Where Are They Now?

The next fall, Harrell, who was All-Metro and named defensive player of the year by the Post-Intelligencer, and Steele, a 1975 All-American, were stars of Don James's second recruiting class at the University of Washington. They were starters and teammates on the 1978 Rose Bowl team that beat Michigan 27-20.

Steele became the UW’s single-season rushing leader in 1978 (1,111 yards – a record that lasted until Greg Lewis broke it on October 27, 1990). He became the school’s all-time rushing leader in 1979. His career rushing record of 3,168 yards stood until Napoleon Kaufman topped it on Sept. 24, 1994 (Kaufman finished with 4,106. He was an All-America honorable mention, was a 1996 Husky Hall of Fame inductee, and launched a successful commercial real estate career. Steele was drafted by the Seahawks in 1980, but the lingering effects of a college knee injury – three torn ligaments in his right knee – ended his professional career after training camp. "I remember getting teary-eyed when I saw (Steele) get hurt," Harrell said of the 1979 injury. "I’d never seen him go down. He was Superman to me. I gave him the best shots I had coming out of high school and he took them" (Harrell interview).

Blanchet running back Ken Gardner and two-way starting lineman Trip Rumberger were also UW stars. So was Garfield receiver Anthony Allen, who was locker partners with future NFL Hall of Fame quarterback Warren Moon. Allen, Gardner, Harrell, Rumberger and Steele were teammates when the Huskies beat Texas 14-7 in the 1979 Sun Bowl. Gardner became a mortgage consultant in Seattle. Williams, who caught the winning pass in the Metro championship game, became owner of The Williams Company, a custom homes and expansive remodels company in the greater Seattle area.

Harrell, who with a 3.98 grade-point average, was Garfield’s valedictorian, was a Husky All-America honorable mention in 1979 and went to UW law school instead of pursuing a football career. As an attorney, one of his clients was Rumberger’s Bellevue-based window-and-door company. Harrell received the UW Distinguished Alumni award in 2007, the year he won his first Seattle City Council race, and in 2013 was inducted into the Northwest Football Hall of Fame. Harrell served as Seattle City Council President from 2016 until January 2020. He served as acting Seattle mayor for six days in 2017 following the abrupt resignation of mayor Ed Murray. Harrell was elected the 57th mayor of Seattle in November 2021, beating former city council colleague M. Lorena González with 58.56 percent of the vote.

Kevin Powell, who played semipro football, went to work for Boeing. Darrell Powell played one year at Tennessee State, where he earned an undergraduate degree in accounting. He later earned an MBA from Harvard Business School, became chief operating officer for the United Way of King County, and also worked as Chief Finance Officer for the YMCA of Greater Seattle. On January 29, 2024, the King County Regional Homelessness Authority’s implementation board unanimously voted to approve Powell as the new interim CEO. He remained in the role until June 3, 2024.

Anthony Lyndell Jones became a cornerback at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, played with the Atlanta Falcons in 1987, and later became a Seattle Police officer and football coach at Seattle’s O’Dea High School. After the UW, Anthony Allen started his professional career in 1983 with the United States Football League. He played with three NFL teams from 1985-1989, including Washington, where he became a 1987 Super Bowl champion. After his NFL career, Allen returned to coach Garfield’s football team with Roberts as co-head coaches. Allen was later the solo head coach through the 2010 season.

Bill Herber, an assistant coach on Blanchet’s 1975 team, was inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2015 and continued as an assistant wrestling coach into his mid-80s. He is also the namesake of Blanchet’s Herber Hall. Assistant Edd Olson became owner of Olson Energy Service in Seattle. Bishop Blanchet, known as the Braves in 1975, changed its moniker to the Bears on January 26, 2022.

Naish, who was a football and baseball player at Central Washington, where he is part of their Hall of Fame, coached at Blanchet from 1959 to 1987, compiling a 208-109-5 record and the one state championship. The 1975 Metro title was one of Naish’s seven. "He was a great gentleman, kind of an old-school coach, a wonderful person," said George Monica, an 11-year assistant under Naish who took over the program in 1987. "I think the best tribute to Mick, really, is the number of guys who played for him who went on to become coaches themselves. He was a great role model for a number of kids that he coached" ("Longtime Blanchet Coach ..."). Bishop Blanchet now plays its home games at Mickey Naish Field.

Al Roberts, who started coaching at Mercer Island following his graduation from UW, continued as Garfield’s coach through the 1976 season. He then joined Don James’s UW staff as running backs coach through 1982, when he left to join the staff of the Los Angeles Express of the United States Football League. After stints at Purdue University and the University of Wyoming, Roberts was an NFL assistant coach (special teams) from 1988 to 2002. In 2006, he returned to Garfield as co-head coach with Allen. Roberts later became an O’Dea High special teams coach and helped the Fighting Irish win the 2017 state championship.

"I coached in three playoff games with the Eagles, one with the Jets; I coached against the greatest athletes in the world in NFL football," Roberts said in 2006. "I coached in three Rose Bowls, all that kind of stuff; and the greatest game of my life was Garfield-Blanchet, four overtimes. That's the greatest" (Roberts interview).

LINE SCORE

1975 Metro League Championship

November 7, 1975

Memorial Stadium, Seattle

Blanchet 42, Garfield 35 (4OT)

Blanchet 7, 7, 0, 0, 7, 7, 7, 7 – 42

Garfield 0, 7, 0, 7, 7, 7, 7, 0 – 35

BLAN: Steve Williams 26 pass from Frank Vaculin (Dave Augustavo kick)

BLAN: Joe Steele 3 run (Augustavo kick)

GAR: Anthony Allen 27 pass from Darrell Powell (Tim Cottongim kick)

GAR: Teddy Martin 45 run (Cottongim kick)

GAR: Kevin Powell 5 run (Cottongim kick)

BLAN: Ken Gardner 8 run (Augustavo kick)

BLAN: Steele 2 run (Augustavo kick)

GAR: Martin 1 run (Cottongim kick)

GAR: Kevin Powell 8 run (Cottongim kick)

BLAN: Steele 5 pass from Vaculin (Augustavo kick)

BLAN: Williams 11 pass from Steele (Augustavo kick)