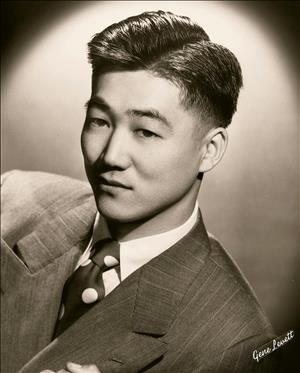

James "Jim" Kazuo Okubo, World War Medal of Honor recipient, was born in Anacortes in 1920 to hard-working Japanese immigrants. He grew up in Bellingham – industrious, well-liked, and active in school sports and clubs. Following graduation from Bellingham High School in 1938, he enrolled in a pre-dental program at Western Washington College of Education. Life changed overnight when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, hurling the United States into war. Longtime neighbors and friends who looked like the enemy were suddenly suspects and spies. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 – paving the way for the forced removal and imprisonment of 120,000 U.S. civilians of Japanese descent. In June 1942, 33 Whatcom County residents, including Jim's family, were forced to board a bus in front of the Okubo home on the way to Tule Lake Relocation Center in Northern California. When the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team was formed, Jim left his family behind barbed wire to serve as an Army medic. He survived the war but died in a 1967 car accident, 33 years before receiving top military honors for extraordinary valor in one of the bloodiest battles in Europe in 1944.

"Extraordinary Heroism"

James Okubo's hero story is one of selfless courage propelled by his instinct to care for and about other people, and the bravery and brotherhood of the Nisei (second generation Japanese American) soldiers with whom he served. The citation on his Medal of Honor, conferred on June 21, 2000, by President Bill Clinton, reads:

"For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Technician Fifth Grade James K. Okubo distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism in action on 28 and 29 October and 4 November 1944, in the Forêt Domaniale de Champ, near Biffontaine, eastern France. On 28 October, under strong enemy fire coming from behind mine fields and roadblocks, Technician Fifth Grade Okubo, a medic, crawled 150 yards to within 40 yards of the enemy lines. Two grenades were thrown at him while he left his last covered position to carry back wounded comrades. Under constant barrages of enemy small arms and machine gun fire, he treated 17 men on 28 October and 8 more men on 29 October. On 4 November, Technician Fifth Grade Okubo ran 75 yards under grazing machine gun fire and, while exposed to hostile fire directed at him, evacuated and treated a seriously wounded crewman from a burning tank, who otherwise would have died. Technician Fifth Grade Okubo's extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit on him, his unit, and the United States Army" ("James K. Okubo").

Beginnings in Anacortes

Okubo's personal beginnings mirrored those of many other children of immigrant families who worked in the resource-extraction industries of the Pacific Northwest. His father, Kenzo (d. 1943), had been a cook on freighters and passenger ships before arriving with his future in-laws at Tacoma in 1900 at age 20. They were part of a 25-year-long influx of Japanese immigrants, the Issei, which began with an open-door policy made possible by a treaty signed in 1894 that guaranteed the Japanese entry into the United States. Bit by bit, however, those rights eroded as tensions between the nations grew. The 1907 Gentleman's Agreement was enacted allowing only families of immigrants already residing in the U.S. to immigrate; next, the Alien Land Act of 1913, which prohibited Japanese from owning or leasing land for longer than three years; and ultimately the 1924 Immigration Act, which prevented all Asians from admission to the U.S., even those not previously restricted, specifically the Japanese.

Kenzo worked as a deck hand on local commercial sailing ships until marrying Fuyu Kanzaki (1884-1974) at the U.S. Immigration Office in Seattle in December 1907, two days after she arrived from Yokohama. Their first son Hirami "Hiram" (1908-2004) was born in Anacortes. From there, they moved to Port Blakely on Bainbridge Island, where Kenzo worked as a cook in a salmon cannery, and then to Eliza Island for work in a fertilizer plant. They returned to Anacortes in 1911. Son Sumi (1913-1993) came along in 1913 and daughter Tomiko "Tomi" (1915-2010) in 1915. The entire family made a short visit to relatives in Japan and returned in time for their next daughter Hime's (1917-2015) birth in 1917. They welcomed James on May 30, 1920. In a 1992 letter, Tomi recalled living on Oakes Avenue in Anacortes, near the beach where the siblings spent much of their time playing.

Jim was only a year old when the family moved to Seattle, where his father ran a restaurant on King Street and later a butcher's shop. The youngest child, John, was born in Seattle in 1923. But long hours at the restaurant and the failure of the shop took their toll. In 1924, Kenzo moved the family back to Anacortes and returned to fishery work.

Combining Families in Bellingham

When Jim Okubo was 6, his maternal aunt, Yukino Kunimatsu (1879-1927), died suddenly of heart failure in Bellingham. His father and mother moved to Bellingham to take over operation of her restaurant, the Holly Tea Parlor, from the widowed brother-in-law, Isekichi. Without hesitation the Okubos also "adopted" the youngest six of 11 Kunimatsu children still at home to raise with their own six, which now included Fuyu's daughter, who was born in Japan. The blended family lived in the Kunimatsu's rented home at 1406 H Street. The cousins became as close as siblings their entire lives.

Bellingham's small Japanese population ran several businesses, including eateries, barbershops, billiard halls, and a mercantile, along the Whatcom waterfront that catered to Japanese laborers. The first Japanese immigrated there after an expulsion of Chinese workers in 1885. According to the 1900 census, 213 out of 24,116 Whatcom County residents were identified as Japanese, up from 81 in 1890. Many were employed in jobs held previously by seasonal Chinese laborers at Pacific American Fisheries in Fairhaven – the world's biggest salmon packing plant – in sawmills, and on railroads.

Bellingham struggled with racial intolerance. Confrontations between white and Asian residents, including Filipino and East Asians, and between immigrant groups, were reported in local newspapers on a regular basis. On September 7, 1907, a labor dispute fueled an angry mob of white men to violently drive all South Asian laborers, along with remaining Chinese and some Japanese, out of town. Although it became known as the Hindu Riot, the majority were followers of Sikhism. Accounts vary as to why a number of Japanese residents were spared the mob violence. The Japanese had already made obvious efforts to establish themselves in the community. They held Christian services and established a Japanese and English language school in 1905 at the First Baptist Church, enrolling 12 students. Some had made white friends. The local Japanese Association encouraged assimilation by teaching classes in civics among other things. But prejudice and fear of the "Orientals" remained.

Those few like the Okubos, who were lucky enough to establish stable homes, focused on raising their American-born children, the Nisei, to prosper and be good Americans. Very few Nisei were taught Japanese beyond what was needed to communicate with their parents. By the time the Okubos moved to Bellingham, the anti-Asian immigration movement along the entire West Coast had reached its apex.

The Okubos ran the Holly Tea Parlor at 433 W Holly Street from 1928-1930. In 1931 they took over the Sunrise Café at 600 W Holly Street, whose previous proprietor, Umekichi "Tom" Tsutsui (b. 1868), was considered a pioneer Japanese of Bellingham. Kenzo cooked, Fuyu managed the front of the restaurant, Tomi and Hime worked as waitresses. The boys helped on occasion. The older boys also worked in Alaska during summers canning salmon and at Blanchard, south of Bellingham, shucking Pacific oysters, introduced from Japan, for Point Rock Oyster Co. During the school year, they enjoyed the same activities as their non-Japanese friends – playing football, baseball, and tennis; fishing, boating, clamming, and skiing at Mount Baker. Sumi was especially athletic, competing in city tennis tournaments and semipro baseball. The girls joined high school clubs and were elected to ASB offices.

After graduating from Roeder Junior High and Whatcom High School, the older siblings and cousins began leaving Bellingham. Brother Hiram and cousin Saburo (1915-2002) enrolled in the University of Washington in Seattle. Cousins Umeko (1910-1971) and Tsune married and left home. Brother Sumi moved to Los Angeles in 1934 to work in the produce business. They lost the youngest sibling, John, in 1936 at age 13, to leukemia, a week after his mother was summoned back from another visit to Japan. Jim graduated as a top student with the first class of the brand-new Bellingham High School in 1938. Cousin Saburo went to work in Wapato around 1940. Brother Hiram joined the U.S. Army in 1941.

A Dream Interrupted

Okubo's goal was to become a dentist. He enrolled in prerequisite courses at Western Washington College of Education (WWC) while continuing to help his parents in the restaurant. By all accounts, he thrived as a college student. He was well-liked by other students and faculty and participated in student activities, including the Schusskens (Ski) Club and Interclub Council (ICC) of club presidents. The ICC was the center of student organizations. Members were charged with promoting student clubs to incoming freshmen and organizing extracurricular activities such as rallies, shows, and pre-election nominating conventions. WWC was a teacher-training college at the time – focused on providing students with the wide variety of experiences that a teacher would need. It was a dream come true for a good student like Okubo, until it wasn't.

Pearl Harbor was not a household name before December 1941. President Roosevelt had ordered the relocation of the U.S. Pacific Fleet to the naval base there from the West Coast during the spring of 1940 as a show of power against Japan. The surprise attack by the Japanese early on December 7 killed 2,400 U.S. military personnel, unexpectedly plunging the U.S. into full-scale war.

The attack shocked Japanese residents in Hawaii and the States. The Nisei were ready to defend the country of their birth. Indeed, Hawaiian Japanese had already been serving in the Territorial Guard, from which they were immediately discharged. Wartime hysteria engulfed all reason. Two days after Executive Order 9066 was signed, Washington Governor Arthur Langlie (1900-1966) declared the state a protective defense area, making Nisei men in the state ineligible to serve in the military. The army began preparation to remove all persons of Japanese descent from designated military zones along the entire West Coast. On March 30, under Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1, all 227 Japanese residents of Bainbridge Island became the first in the nation to be forcibly removed from their homes. At the same time, all Japanese American men of draft age, regardless of domicile, were classified as "IV-C" or "enemy aliens" who could not enlist in the armed forces.

Okubo was a sophomore at Western. The shock of the attack, followed quickly by a nation seeking retaliation against loyal Americans who looked like the enemy, was a double blow. By March he knew he would have to drop out of school to help his family prepare for the inevitable. While other Japanese students had enrolled briefly at Western, he was the only full-time student not able to continue because of Executive Order 9066. In April, he bade farewell to fellow students at a good-natured Evacuation Party in his winter quarter zoology class. He gifted classmates with objects to be left by his family as they decided what little they could carry with them to an unknown future – a piece of rubber, blackout paint, a Japanese newspaper, other novel items, as well as a box of candy.

Civilian Exclusion Order No. 90, dated May 23, 1942, was soon posted in the Northwestern Sector. It declared that all persons of Japanese ancestry living in the counties of Whatcom, Skagit, Snohomish, Island, and San Juan, along with designated portions of eastern King County, were to be evacuated by 12 noon PWT (Pacific War Time), Wednesday, June 3. No "Japanese person" was to leave or return to the designated martial areas after 5 a.m., May 23, without seeking special permission of the representative of the Commanding General at either one of the Civil Control Stations, located at 1801 Hewitt Avenue, Everett, or the Burlington Fire Station.

Ten days later, 6-year-old Pat Shima, the youngest evacuee, was photographed clutching her doll as she sat on the front steps of the Okubo home, waiting with the remaining 32 residents of the Whatcom County Japanese community to board a bus to Burlington, the first step in their journey to Tule Lake Relocation Center in Northern California. Other county residents may have previously moved south to join family before they were separated. There was also a two-week period allowing people to self-evacuate to the interior, away from the exclusion zones. No record has been found of how many laborers were deported or taken into custody from the surrounding businesses.

Leaving for Tule Lake

In the short time all residents to be relocated were given to prepare for departure, they gave up all possessions they could not carry and any property they owned to unscrupulous buyers and empty government promises, or simply had to abandon them. Unlike some close-knit Bainbridge Island residents, who found sympathetic neighbors and friends willing to watch over their houses and farms, the small Bellingham community had no such tangible support. There were some who showed kindness, such as the Okubos' neighbor who offered them a place to stay if needed, and the Wahl family, whose founder had befriended Harry Shima, young Pat Shima's father.

According to War Relocation Records, none of the departing Okubo/Kunimatsu Nisei had attended Japanese language school. They were all listed as Christians. Jim and Hime had never been to Japan, not even to visit, and Jim was on record as speaking English only. Their blended family represented nearly a fourth of the Bellingham evacuees.

A Bellingham Herald photo captured the moment on June 3, 1942, that the bus to Burlington began loading its passengers. As in well-documented coverage of the evacuation along the entire coast, the departing residents were dressed in their best clothing – standing with dignity and gaman, the deeply-ingrained Japanese determination to patiently persevere in the most difficult situations. That James, his siblings, and cousins had become such well-rounded contributing members of the Bellingham community at large is a huge testament to the hard work of his parents, who wanted nothing better. Being forced to leave all that behind must have taken as much gaman as they could muster. The caption on the photo read:

"The big bus that started Whatcom County Japanese on their way to the Tule Lake assemble center in Northern California Wednesday received many of its passengers at the Kenzo Okubo residence, 1406 H street. There several families had assembled their personal effects. The photograph shows the first of them boarding the bus for Burlington. There they boarded a train for Tule Lake. Okubo left his home with a 'for sale' sign on the front wall. The government is storing heavy pieces of furniture and household furnishings for the Japanese until they return. The Burlington assembly of Japanese from Whatcom, Skagit, San Juan and Island counties, totaled ninety-seven. An additional fifty-seven were picked up at Everett, more at Seattle" ("All Japanese Here ...").

None of the mostly longtime residents of Bellingham who boarded the bus that day returned to Bellingham or Whatcom County.

Barrack 1302-D

Although the bus led to another day-long train ride directly to Tule Lake, their final destination, the Northwestern Sector incarcerates bypassed "Camp Harmony," a name for the state fairgrounds in Puyallup, where 7,500 Issei and Nisei from Seattle and rural areas around Tacoma were forced into unsanitary, miserable temporary quarters until their transfer to the Minidoka Relocation Center in Jerome, Idaho.

Required incarceration intake forms included reference letters from neighbors who described the Okubo family as model citizens, loyal Americans, and highly respected members of the community. They had not received any public assistance, nor did they have foreign interests. They were considered in good standing at the Mount Baker Grocery, where they purchased the food for their restaurant and paid bills on time. Fuyu was held in high regard as a model mother and homemaker who donated annually to the American Red Cross.

Tule Lake Relocation Camp, complete with guard towers and barbed wire, opened the week before their arrival. The eight-member family was assigned a one-room apartment heated with a small coal stove in a leaky tar-paper barrack numbered 1302-D. Life was incredibly challenging. Facilities were all communal, requiring users to stand in line, often in adverse weather. All facilities, including the hospital and schools, were staffed by inmates. Any payment was minuscule.

Okubo wrote to his former student newspaper at Western, the WWC Collegian, which published an article under the headline "Camp Dentist From WWC" in the October 23, 1942, edition, on his rosy report of life in Tule Lake:

"James Okubo, a former pre-dental major at WWC, with a good scholastic record, is now at Tule Lake, California. In a Japanese Relocation center. James says the camp is nice except that he longs for some good Washington rain, and every time he sees a scorpion, it makes him hungry for shrimp.

"They live in barracks which are more or less houses or dormitories. Each block of barracks has a representative in the council which governs the camp. Each block also has a mess hall, laundry, and other necessary facilities. The camp is going to put up a theatre, financed by the profits of the various stores.

"At the present time James is assisting in the hospital wards of the camp. He says the doctors and nurses are very helpful to medical students and he still has hopes of going to a university in the Middle West and continuing his education" ("Camp Dentist ...").

Five months later, Kenzo Okubo, who had lived his life providing food for his family by cooking for others, died at age 64 of bronchopneumonia. He had refused to stop work as the camp's chief cook to recover from a bad cold and other more serious health issues.

From Incarceration to War Hero

Meanwhile, the war raged on in Europe and the Pacific. On February 1, 1943, President Roosevelt authorized the creation of a combat team consisting of "loyal American citizens of Japanese descent." His letter declared, in part, that "Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry" (Roosevelt to Stimson). Ironically, nearly all of the 1,500 mainland Nisei who responded to the call for volunteers to serve in the newly formed 442nd Regimental Combat Team were recruited from behind barbed wire. The other two thirds were Hawaiian Nisei. Thousands of other Hawaiian Nisei volunteers were already in training for what was to become the segregated 100th Infantry Battalion. They had not been imprisoned.

Despite their father's objections, all three of the Okubo sons and two nephews enlisted in the 442nd RCT and one in the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). Because of his medical background in the camp, Jim became a Technician, Grade 5, attached to the Medical Detachment, K Co., 3rd Battalion of the 442nd RCT. The 442nd began training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, in May 1943. Their motto became "Go For Broke," symbolizing their willingness to risk everything to win the war in Europe and the battle against racial prejudice at home, and to prove their loyalty to the United States. At Camp Shelby, medics trained separately, focused on saving lives on the battlefield, with only cursory training on how to march and fire a weapon.

The 100th Infantry Battalion shipped out in September 1943. The following June, the newly trained 442nd arrived in Italy to fight alongside the heavily depleted ranks of the 100th. The war really hit home for Jim when his cousin Isamu "Eke" Kunimatsu (b. 1921) was killed in action in Italy on July 12, 1944. Just months later, Jim was engulfed in one of the worst battles of the war – the drive to save the "Lost Battalion" of Texans in the Vosges Mountains of France. His reputation as a medic grew quickly after that, as attested in letters home from his older brothers.

The legendary actions of the 100th/442nd RCT in the liberation of Italy and France earned the respect of military leaders and ensured their place in history as the most highly decorated unit of its size and length of service in U.S. military history. President Harry Truman praised their bravery and personally presented them with one of their seven Distinguished Unit Awards. Despite their heroism and heavy sacrifices, only one Nisei soldier, PFC Sadao Munemori (1922-1945), was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor at the end of the war. It had been upgraded from a Distinguished Service Cross. PFC Munemori threw himself on a live grenade to save his comrades.

Belated Recognition

Miraculously, Okubo was never wounded and suffered no physical disabilities from the war. His brothers Hiram and Sumi were not so lucky. Their wounds caused lifelong problems. Sumi was especially resentful that his athletic career ended that way, according to his son, Kenzo. After the war, Jim joined his mother and sisters in Detroit, where they had moved when released from incarceration. He enrolled in Wayne State University, where he met his wife Nobuyo "Nobi" Miyaya. From there he earned a dental degree and a Master's degree at the University of Detroit, where he became a respected professor and researcher. His sardonic sense of humor resurfaced in his fondness for giving students pop quizzes on December 7.

Like many other Nisei, he shared little of the hardships that he and other Japanese Americans had suffered with his children or others. They practiced shigata ga nai, which means nothing can be done about it. Move on. He still loved to ski and was on a family ski trip, January 29, 1967, south of Flint, Michigan, when their car slid on an ice patch and slammed into another car, killing him. He was 46. No one else in his family was injured because he made them wear seatbelts, even though it was not yet a law.

In 1996, U.S. Senator Daniel Akaka (1924-2018), a World War II veteran from Hawaii, asked for a review of service records of Asian American and Pacific Islander soldiers who served in the war. Twenty-one were determined to be eligible to receive a Congressional Medal of Honor. A week before the award ceremony at the White House, Sen. Akaka learned of Okubo's actions in France and hastily submitted a bill to authorize the same award to James K. Okubo. S 2722 reads, in part:

"Mr. Okubo (Tec 5) served as a medic, member of the Medical Detachment, 442nd Regimental Combat Team. For his heroism Displayed over a period of several days (October 28, 29, and November 4, 1944) in rescuing and delivering medical aid to fellow soldiers during the rescue of the 'Lost Battalion' from Texas, he was recommended to receive the Medal of Honor. The medal, however, was downgraded to a Silver Star. The explanation provided at the time was that as a medic, James S. Okubo was not eligible for any award higher than the Silver Star" ("Award of Medal...").

On June 21, 2000, President Bill Clinton presented the 22 Medals of Honor to surviving recipients or their families. All but two were members of the 100th or 442nd. Okubo's widow, Nobuye, accepted on his behalf. It was one of many important achievements he did not live to witness – those of his comrades, colleagues, and family. He didn't live to see Ronald Reagan sign the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, a formal apology from the nation for violating the civil rights of Japanese Americans. Nor did he witness the conferring of an honorary degree from Western Washington University on June 15, 2019. His daughter, Anne, said he would have been especially proud of that. He seemed happy there.