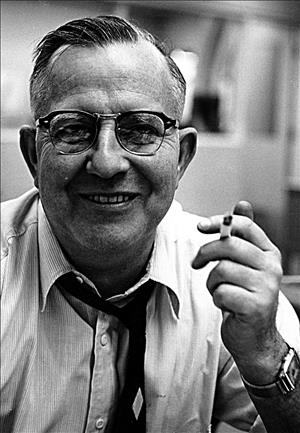

Newspaper editor and author Clifford Curtis Relander, known as Click, was born on an Indiana farm. His mother died when he was four and he was raised for a time by an aunt. His father remarried in 1919 and the family reunited in California. After high school, Relander studied sculpture in Los Angeles. Although his passion for art never waned, he chose journalism as his career. He worked at several daily papers in California before settling in 1945 in Yakima, where he was a reporter and then city editor for the Yakima Daily Republic, a post he held nearly 25 years. He befriended several Central Washington tribes, including the Wanapum and the Yakama, and his interest in their history and culture led him to begin collecting historical manuscripts, books, documents, and other materials. He continued to sculpt in his spare time, including busts of prominent Wanapum Tribe members. His sculptures were displayed in the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles and the Wanapum Heritage Center outside Mattawa, among other locations. After his death, his archive was donated to the Yakima Valley Regional Library (now Yakima Valley Libraries) where it remains the largest manuscript collection in the library's archives and special collections.

In the San Joaquin Valley

Clifford Curtis "Click" Relander was born on January 16, 1908, on a farm near Danville, Indiana. His parents, Carl Frederick (1879-1958) and Lessie May (neé Pearcy) (1885-1912), married on July 21, 1902. He had an older brother, Frank Pearcy Relander (1904-1981). Their mother Lessie was physically frail and the family moved to California on two occasions, hoping that the warmer weather would be beneficial to her health. That was not the case, however, and she died in Exeter, California, on February 7, 1912, at the age of 26. Her younger son Clifford was just four years old at the time.

After his mother died, Clifford was raised in Indiana by an aunt, a former school teacher who encouraged his love of reading and books. The rural lifestyle helped inspire what would later become two of his passions in life: Native American history and sculpting. "As a farm boy there his interest in Indians first began when collecting arrowheads on a farm in Hendricks County, turned up by his plow. He also dug blue clay from a creek bank and used it for his first sculpturing ..." (Loraine Relander to Herb Shriner).

In 1919, his father married Pearl Annie Baker (1887-1977) and the family was reunited in California. After completing high school, Relander went to Los Angeles to study sculpting. Although his interest in sculpting continued throughout his lifetime, it was his love of reading and storytelling that led to his chosen career as a journalist. Relander was a reporter for two California papers serving the San Joaquin Valley: the Visalia Morning Delta (later called the Visalia Times-Delta) and the Fresno Bee. Occasionally while on a story assignment, Relander would go up in an airplane to photograph floods or landslides. He quickly realized that an aerial perspective could provide more accurate observations and add depth to his reporting. In 1939, he obtained his private pilot's license.

In his free time, he continued to sculpt. He was fascinated by the distinctive facial expressions and physical characteristics of the San Joaquin Valley Indians, completing several busts of local tribal members. His artistic eye and attention to detail were as important as his research and writing skills, making his stories on the history, traditions, struggles, and triumphs of Native Americans come alive.

In 1938, Relander married Montana native Loraine (also spelled Lorraine) Peterson, who had been society editor of the Visalia Times-Delta.

Move to Yakima and Work with the Wanapum

In 1945, Relander moved to Yakima, where he became a reporter and then city editor for the Yakima Daily Republic (which merged with the Yakima Morning Herald to become the Yakima Herald-Republic in 1968), a position he held until his death in 1969. While in Yakima, he began to study a small tribe of Native Americans called the Wanapum living nearby on the Columbia River. For millennia they lived along the river from Priest Rapids, just upstream of what is now known as Hanford Reach, to below the mouth of the Snake River. In fact, the tribe's name means "river people." About 3,000 strong in the early nineteenth century, the Wanapum in 1805 met Lewis and Clark, who referred to them as the Sokulks, at the confluence of the Snake and Columbia. By the time Relander began researching the tribe in the 1940s there were only a handful of members left, clinging to their homeland along the Columbia and trying to keep their traditional customs alive.

Relander wrote often and eloquently about the Wanapum, documenting their culture and history and how they faced challenges posed by the incursion of the non-Native world. Considering it a moral duty, he helped the tribe on many levels, from publicizing Wanapum concerns about the construction of dams in the Priest Rapids area to helping a tribal member get a driver's license. In time he became a trusted and beloved confidante of the deeply religious tribe and in 1949 was adopted and given the Wanapum name of Now-Tow-Look, which means Hovering Hawk. He used his Indian name, along with his birth name, on the title page of each of his four books.

"If you go to Priest Rapids on the Columbia river during one of the Wanapum Indian feasts and see a blanket-clad white man going through the traditional rites with the Indians, you can be fairly safe in betting that it is Click Relander of Yakima, who has been given the Wanapum name of Now Tow Look (Hovering Hawk).

"Relander, a newspaperman, has been waging a one-man campaign to help preserve and publicize the culture of the Wanapums and other Northwest Indians.

"His letter-writing alone has been prodigious -- 3500 in the last five years on Wanapum problems" (Van Arsdol).

His work with the Wanapum climaxed with Relander writing Drummers and Dreamers: The Story of Smowhala the Prophet and His Nephew Puck Hyah Toot, the Last Prophet of the Nearly Extinct River People, the Last Wanapums, published in 1956 and considered the definitive history of the Wanapum people. A reviewer noted:

"[T]he book is written in vivid, colorful language, fast-paced and authoritative. It contains no mythical characters or fictionalized plot, but the very impact of the unfolding events pulls the reader along from the opening line to the last page ... Few, if any, men are as well qualified as the author to write the story. For years he has been an intimate friend of the Wanapums and other Indians. He has helped them with business advice, written letters for them, and visited in their homes ... This, coupled with Relander's extensive study of Indian lore of the Pacific Northwest, has resulted in a well selected, carefully documented story" (Jenkins).

In 1956, the book won an award of merit from the American Association for State and Local History.

Relander invited Wanapum tribal members to join him on a book tour in the fall of 1956. His wife Loraine provided additional details in a letter, commenting that she needed to buy "some eagle feathers and a special kind of blanket suitable for the old man leader of this band [Wanapum], who is named Puck Hyah Toot. He would need this when he and others accompan[y] my husband on a book tour of the Northwest starting October 6. This tour is to include over 20 cities -- including Portland, Seattle and Spokane -- which though not farther than 200 miles from Yakima, have never been visited by the old Wanapums, who are extremely poor people ... The Wanapums lived at one of their last villages at White Bluffs several years ago when the Atomic Energy Commission established the Hanford Atomic Works, but because the government needed the land, they moved out to their last home at Priest Rapids" (Loraine Relander to Herb Shriner).

In 1959, construction began on the Wanapum Dam on the Columbia, about 15 miles upriver from Priest Rapids and six miles below Vantage. When it opened in 1966, Relander took it upon himself to lobby for jobs and housing for the remaining Wanapum tribal members who had been displaced.

Friend of the Yakama Nation

While researching the Wanapum people, Relander also became interested in the Yakama Nation. In 1952, he testified on the tribe's behalf in a water-rights dispute. A few years later, he was asked by tribal members to edit and contribute material to a book they were planning to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of 1855 that established the 1.3 million-acre Yakama Reservation. The result was Treaty Centennial: 1855-1955, the Yakimas, which "tells the story of the Treaty Council at Walla Walla, creation of the Yakima Reservation, fisheries, timbering and bits of tribal lore ... Events leading up to the Treaty Council, the result of the westward migration and settlement of the Northwest, are chronicled in the treaty history section which is based on extensive research ... The editor said that it was the wish of the tribe that as wide a scope as possible be covered in the short time available, in order that a publication could be compiled that would serve as a reservation handbook" ("Yakimas Publish ...").

Although Relander's books were well-received by the scholarly community, he was frustrated that they were not reaching a larger audience. He switched to writing fiction, hoping it would have broader appeal.

"He began work on two manuscripts, Sorority Row and The Lonely Road and for three years wrote and revised these stories. He contacted a literary agent, Laura Wilch, to promote his works with New York publishing houses but to no avail. Though apparently aware of the difficulty of selling a manuscript in the commercial market, Relander was sorely disappointed when neither of his works succeeded" (Rankin, 3).

By the early 1960s, Relander was back to writing nonfiction. In 1962 he published Strangers on the Land: A Historiette of a Longer Story of the Yakima Indian Nation's Efforts to Survive Against Great Odds. The historical account describes the economic and social development of the Yakama Tribe beginning with its first encounter with non-Native settlers.

Collecting and Sculpting

Relander's interests extended beyond Native American history and culture. He wrote about many aspects of Pacific Northwest history, from navigating the Columbia River to the small towns and pioneers of Central Washington. He was also curator-director of the Washington State Historical Society and a trustee of the Yakima Valley Museum.

"As chairman of the research committee of the Fort Simcoe at Mool-Mool Restoration Society, he participated in the effort to preserve the former Army outpost and Indian boarding school as a historical site.

"He was also involved in the efforts to establish a museum to preserve Yakima County's history, the Yakima Valley Museum, and was part of a group that helped acquire the Gannon Museum of Wagons collection for the Yakima Frontier Museum, which stood where the Yakima County jail now stands" (Meyers).

In 1961, he served on the advisory council for the state's observance of the Civil War Centennial, organized under Governor Albert D. Rosellini (1910-2011).

Throughout his career, Relander continued to sculpt in his free time. His work was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.; the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles; and the Wanapum Heritage Center, among others. His sculpture helped document prominent Wanapum tribal members, such as Alice Slim Jim Charley and Puck-Hyah-Toot, a tribal leader also known as Johnny Buck and one of the last to speak the Wanapum language. He encouraged the Grant County PUD to display the busts in the Wanapum Heritage Center that the PUD, in conjunction with tribal members, opened in 1966 near the Priest Rapids Dam outside Mattawa. "Mr. Relander's work for the PUD exemplifies the intensity of his labors. After eight to ten hours at the newspaper office, he would often work eight or more hours sculpting. To facilitate his historical research, he purchased a microfilm reader and personally transcribed thousands of pages of microfilm, books and newspapers" (Rankin, 3-4).

Relander and his first wife had divorced, and on August 26, 1963, he married Virginia C. Derby, known as Ginny. A native of New York, she was 32 years younger than Relander. The couple divorced on September 25, 1969.

Relander died on October 20, 1969, at the age of 61, after being treated for a heart condition and respiratory infection. He is buried in Priest Rapids Cemetery, a tribal cemetery in Central Washington on public land owned by the Grant County PUD.

The Relander Collection

Over the decades Relander, a voracious collector, amassed an extensive archive of books, papers, documents, microfilm, photographs, audiotapes, and ephemera related to Pacific Northwest history and Central Washington tribes. In all, it filled about 400 cartons. After his death in 1969 the collection was sold to a Seattle bookstore, where it remained while several groups vied for its purchase. Thanks to a generous, albeit anonymous, donor, in December 1970 the Yakima Valley Libraries (then known as Yakima Valley Regional Library) became its final repository. The collection is wide-ranging:

"Numerous books reflect Relander's many friendships with writers, including a copy of 'The Hanging Tree,' a 1959 movie that was filmed in Yakima County. The book by Dorothy Johnson is signed by the cast, which included Gary Cooper, George C. Scott, and Karl Malden. Photographs and promotional brochures fill file cabinets; old periodicals line shelves. A commemorative album celebrates Yakima's golden anniversary of 1935, and an R. L. Polk & Co. Directory of Ellensburgh and North Yakima of 1890-91 details a time before Ellensburg dropped the 'h''' (Ayer, "Page by Page ...").

Relander's personal papers make up about 80 percent of the archives. Included are his outgoing correspondence, organized chronologically, and incoming letters, arranged alphabetically by name of the writer. There is everything from bank records and payroll vouchers to his pilot's log and award citations. As he worked on newspaper articles and books, he saved his handwritten notes, some as loose-leaf sheets, others bound in notebooks. The other 20 percent of the collection consists of historical documents as well as materials obtained from organizations with which he was affiliated, such as the Washington State Historical Society and the Fort Simcoe at Mool-Mool Restoration Society. He also collected more than 6,000 books and pamphlets related to the Pacific Northwest, along with stamps, historical scrapbooks, fruit-crate labels, children's books from the 1800s, maps, periodicals, and newspapers dating back to 1893.

Yakima Valley Libraries Archive Librarian Carlos Pelley noted that researchers regularly request permission to use images and documents from the collection:

"[Relander's] interest in historical subjects and extensive collection of photos captures a snapshot of someone in the early 20th century who earnestly tried to learn more about Native Americans' histories and cultures. Researchers using his collection will discover images of Native feasts, ceremonies, and commentary on the development of dams. His sentiments, reflected in his writings and articles, all indicate that he was a friend to the Wanapum and the Yakama" (Pelley email).

In 2016, the library began digitizing the collection for easier access. The project remains underway in 2024. The Relander Collection is available through Yakima Memory, an online collaboration between Yakima Valley Libraries and the Yakima Valley Museum.