On June 21, 2000, President Bill Clinton awards 22 Congressional Medals of Honor to Asian Americans who had served in the U.S. Military during World War II – all but two to Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans) soldiers in the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Two recipients are from Washington – PFC William Nakamura and Technician 5th Grade James K. Okubo. Both awards are made posthumously to family members. In 1996, Senator Daniel Akaka, a World War II veteran from Hawaii, had asked for a review of service records of Asian American and Pacific Islander soldiers who served in the war. Twenty-one were determined to be eligible to receive a Congressional Medal of Honor. A week before the award ceremony at the White House, Senator Akaka learned of Okubo's actions in France and hastily submitted a bill to authorize the same award to him.

"Loyal American Citizens"

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japanese Americans were not allowed to serve in the armed forces. Instead, 120,000 were incarcerated in remote prison camps for the duration of the war. But on February 1, 1943, President Roosevelt authorized the creation of a combat team consisting of "loyal American citizens of Japanese descent." Long before the medals were awarded, the now legendary actions of the 100th/442nd RCT in the liberation of Italy and France earned the respect of military leaders and ensured their place in history as the most highly decorated unit of its size and length of service in U.S. military history. President Harry Truman praised their bravery and personally presented them with one of their seven Distinguished Unit Awards. Despite their heroism and sacrifices, however, only one Nisei soldier, PFC Sadao Munemori, was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor at the end of the war. It had been upgraded from a Distinguished Service Cross. Munemori threw himself on a live grenade to save his comrades.

A Coveted Honor

The Congressional Medal of Honor is the ultimate recognition of valor in battle – the highest award an American combatant can receive. It is given only to individuals who acted above and beyond the call of duty. No one can receive the medal for having acted under orders, no matter how heroically. General George Patton said he would have given his soul to have received one. Two presidents – Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson – told recipients that they would have rather had the medal than been president. At the White House presentation ceremony, it is customary for the president to salute recipients, who then return the salute. For the rest of their lives, whenever honorees wear their medal, they are always saluted first by any service personnel or veteran, no matter their rank.

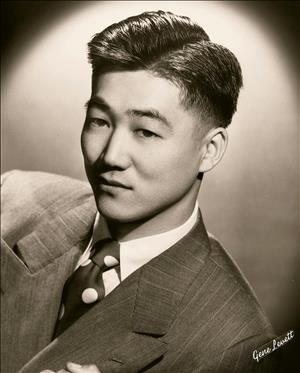

James K. Okubo (1920-1967) enlisted while imprisoned with his family at Tule Lake Relocation Center in Northern California. He became a Technician, Grade 5, attached to the Medical Detachment, K Co., 3rd Battalion of the 442nd RCT. His unit was ordered to save a Texas battalion surrounded by the enemy in the Vosges Mountains of France. Without hesitation he crawled through heavy German fire and into a burning tank to save 25 of his comrades during one of the worst battles in Europe. His courageous actions on October 28 and 29 and November 4, 1944, earned him a recommendation for the Medal of Honor, but at the time he was instead awarded a Silver Star. He was killed in a car accident in Michigan in 1967, and it was another 33 years before a review of his record earned him the Medal of Honor.

William Nakamura (1922-1944) was born January 21, 1922, in Seattle. He graduated from Garfield High School and attended the University of Washington. At age 20, he and his brother George volunteered for service in the U.S. Army. As U.S.-born citizens, they had been unlawfully imprisoned at Minidoka Concentration Camp in Jerome County, Idaho. William was attached to the 2nd Battalion Co. G. 442nd RCT. He received his posthumous Medal for heroism during a fierce firefight near Castellina, Italy, July 4, 1944. He crawled forward under heavy fire to throw grenades into a concealed enemy machine-gun nest, enabling his platoon to advance, and then later remained behind to cover their retreat so that a mortar barrage could be placed. His heroism took his life. The platoon was able to withdraw to safety without further casualties.

In 2001, the U.S. Courthouse in Seattle was renamed the William Kenzo Nakamura Courthouse. That same year, Brooke Army Medical Center on Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, Texas, named their new building the Okubo Barracks. A year later, the Okubo Medical and Dental Complex at Madigan Army Medical Center at Joint Base Lewis-McChord was opened. The base hospital's Okubo Soldier-Centered Medical Home was also named in his honor.