Resembling a long rope frayed at each end, the Oregon Trail stretched across much of nineteenth century North America, linking the populated East Coast with the remote western edge of the continent. A person’s individual westward journey might have started in Maine, Kentucky, or North Carolina, but these narrow paths eventually merged around St. Joseph, Missouri, to form the main body of the Oregon Trail. Once across the majority of the continent, the trail again frayed: one segment heading to the Great Salt Lake, another to the California gold rush, and yet another ending in Oregon Territory. The earliest non-indigenous pioneers to arrive in Oregon had their choice of prime land, usually in rich river bottoms near fledgling communities. Later pioneers who reached the Portland/Oregon City area found the best sites had already been claimed. For this and other reasons, many settlers moved on, heading north toward Puget Sound. They followed and improved an ancient trail – the Cowlitz Trail – developed by Native Americans and fur traders. Today the Cowlitz Trail has segued into what we call the Interstate 5 corridor between the Columbia River and Puget Sound.

Beginnings

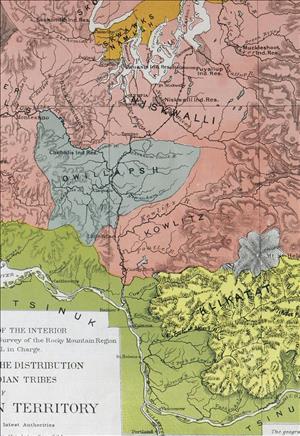

When humans first entered the region thousands of years ago, they no doubt observed animals searching for fresh water, berries, migrating salmon, nuts, and other food sources. By studying these animals and following their paths, humans learned where and when to gather materials needed for daily living. Using existing game trails would have been an easy way to explore the region. Early immigrants established home territories and evolved into tribes, connecting and extending game trails to form their own customary travel routes. As inter-tribal trading grew, people traveled farther afield to gather bartering material, such as camas roots and shellfish for food, obsidian and other rocks for arrow points and knives, and cedar bark and animal pelts for clothing. Trails between the Columbia River and Puget Sound eventually coalesced into a major north-south trade route, connecting the Cowlitz, Chehalis, Nisqually, and Squaxin peoples, as they came to be known, with neighboring tribes.

The Cowlitz Trail’s southern half was primarily on water. Natives leaving the Columbia River paddled up the Cowlitz River in canoes that "were hollowed out laboriously from cedar logs and were so shaped that Lewis and Clark called them 'shovel nosed dugouts.' They were designed to withstand the erosion of sharp gravel in the shallow rapids" (McClelland). Eventually, the Cowlitz River veered east to its source on the slopes of Mount Rainier. Native Americans left the river near present-day Toledo and continued due north on foot in order to reach Puget Sound.

Early Explorers, Fur Trappers

Although Europeans explored the Pacific Northwest coastline as early as the late 1500s, they primarily stayed on their sailing ships. Early explorers such as Peter Puget, Robert Gray, and George Vancouver sighted and in some cases sailed into the Columbia River and Puget Sound, but did not investigate the land between these two great water features (land that would eventually become Southwestern Washington). Even the legendary Lewis and Clark expedition stayed mostly on the shores of the Columbia. Not until 1811 did a party from the Astor Fur Company venture up the Cowlitz River in a small ship’s boat. Just over a decade later, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) established Fort Vancouver, a substantial trading post, on the banks of the Columbia. HBC fur trappers began dispersing throughout the Northwest, running their own trap lines, as well as trading with the local tribes for furs.

The HBC soon determined that more forts were required to serve their burgeoning fur trade. Therefore, Fort Langley, in today’s British Columbia, and Fort Nisqually, near today’s DuPont, were established. Soon after, the HBC formed the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, with an extensive farm near present-day Toledo, and another near the mouth of the Nisqually River. Frequent journeys between these forts and farms helped develop the Cowlitz Trail into more of a recognizable roadway, rather than a mere footpath through the wilderness. Still, the trail was limited to travel by foot and horse, although sheep and cows were also herded over it. In 1833, Dr. William F. Tolmie journeyed from Fort Vancouver to Puget Sound. He described a portion of his trek:

"Our course lay through rich and level praries and prairions or smaller plains, separated from each other by belts of wood from 100 paces to ½ mile wide, through which the road, or trail was execrable, knee up in water and mud, or laid out in ridges or deep furrows formed by large roots extending across, or obstructed with trunks of trees of large dimensions, and at the same overarched with low branches, so that while the horse sprang over the obstacle, were between the devil and the deep sea, and to avoid being entangled in the branches above, had to cling to the horses neck" (Meany).

Rather than depending solely on native dugout canoes for river passage, the HBC also used bateaus. "A bateau was a large flat bottomed boat pointed at both ends, 30 to 32 feet long with a beam of 5 ½ to 6 ½ feet. The craft was built of quarter-inch pine or cedar boards, light enough to be carried across portages by a crew of eight men" (McClelland).

Pioneers

By the 1840s, Euro-Americans were traversing this area on their way to Puget Sound. Heading north to the Sound was generally motivated by the same reasons that people came west in the first place: racial freedom; free land; adventure; elbow room; and promotional campaigns that touted rich farmland and economic opportunities.

Families sometimes split up and headed north from the Columbia River by different methods. Women and children were often sent in canoes or bateaus on the Cowlitz River. Settlers who were encumbered with wagons and oxen or horses could not go by water, so instead used a trail along the east bank of the Cowlitz. The river route and the land route converged at Cowlitz Landing (near today’s Toledo). Once reunited, the families made their way overland to Puget Sound. These pioneers were largely responsible for widening the Cowlitz Trail into a road capable of carrying wagon traffic. Coming north in late 1854 was Margaret Hazard Stevens, wife of newly-appointed Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862). Mrs. Stevens wrote of her trip on the Cowlitz River:

"We were placed in the canoe with great care, so as to balance it evenly, as it was frail and upset easily. At first the novelty, motion and watching our Indians paddle so deftly, they seize their poles and push along over shallow places, keeping up a low, sweet singing as they glided along, was amusing. As we were sitting flat on the bottom of the canoe, the position became irksome and painful. We were all day long on this Cowlitz river. At night I could not stand on my feet for some time after landing. We walked ankle deep in mud to a small log house, where we had a good meal" (McClelland).

Two other routes to Puget Sound were available to Oregon Trail travelers. Those who reached the Portland area could elect to board a ship, go down the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean, then navigate around the Olympic Peninsula and enter Puget Sound from the north. Starting in 1853, Oregon Trail pioneers who reached the Walla Walla area could traverse the rough-hewn Naches Pass trail, which crossed the Cascade Mountains just north of Mount Rainier. This was a more direct route to the southern stretches of Puget Sound, but offered its own pitfalls through the mountains, and was used by pioneers for only a few years. The bulk of pioneer traffic from the Columbia River to Puget Sound continued to utilize the Cowlitz Trail route.

Military

Beginning in the early 1850s, the U.S. military wished to establish a better route between Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River and Fort Steilacoom on Puget Sound. (The military Fort Vancouver was located adjacent to the HBC Fort Vancouver.) The proposed road was developed with federal money but local pioneer labor. (Settlers often paid their annual mandatory "road tax" with labor rather than with scarce cash.) This road roughly followed the west bank of the Cowlitz River, but stayed to higher ground where possible. Predictably called the Military Road, the route eventually cut east to Cowlitz Landing, where it merged with the northern overland portion of the Cowlitz Trail. The Military Road carried troops between forts, but also offered a slightly more convenient passage for U.S. mail and stagecoaches.

Cowlitz Trail Stories

Many pioneers kept diaries or wrote letters home describing the conditions encountered on the Cowlitz Trail. Edward Jay Allen (1830-1915) crossed the Oregon Trail and arrived in the Portland area in the fall of 1852. He wrote about his reasons for going north:

"[Oregon Governor John Pollard Gaines’s] view of the great advantages possessed by Northern Oregon over the Southern portion, and especially of the high destiny of Puget Sound, confirmed the impression I had previous to leaving home, and deepened the resolve I had formed to go on. A great many of the emigrants, too, by this time, had arrived, the majority of whom, together with a large number of the old settlers from the Willamette Valley were going to Puget Sound in the spring. Hitherto public attention had been but little drawn to that part of the country, for the trains of the previous year had, overjoyed at the transition from the dry plains and sterile hills they had crossed, settled in the first valley they had come to, till the best of the lands in the lower country, especially the Columbia and Willamette Valleys were taken up. At least 20,000 had started for Oregon alone this year, 4,000 of whom, it is said, perished by the wayside. The remainder would have to go to the [California] mines, or else northward to Puget Sound, and I was anxious to be ahead of them" (Johnson & Larsen).

Other Cowlitz Trail travelers wrote about specific rough spots along the way. Paul Kane, an artist who journeyed over the Cowlitz Trail in 1847, wrote of the Chehalis area: "We passed over what is called the Mud Mountain. The mud is so very deep in this pass that we were compelled to dismount and drag our horses through it by the bridle; the poor beasts being up to their bellies in mud of the tenacity of bird-lime" (Kane). Phoebe Goodell Judson, pioneer of 1853, reminisced: "Passing over much unoccupied country, where only now and then a hardy frontiersman was clearing up a ranch, we reached Saunders’ Prairie [Chehalis], as it was called, but only a low, open country where for years, during the winter season, travelers were obliged to swim their horses through the swales" (Judson).

North of the infamously swampy land around present-day Chehalis and Centralia, travelers soon encountered the Mima Mounds. Paul Kane wrote: "This [prairie] is remarkable for having innumerable round elevations, touching each other like so many hemispheres, of ten or twelve yards in circumference, and four or five feet in height. I dug one of them open, but found nothing in it but loose stones, although I went four or five feet down" (Kane). To this day, scientists squabble over the origin of the Mima Mounds, which were remarked on by nearly every traveler who wrote about the Cowlitz Trail experience.

Ezra Meeker (1830-1928), famous pioneer of 1852 and tireless promoter of the entire Oregon Trail up until his death in 1928, described the growth of the Cowlitz Trail:

"I have no history of the construction of the later [stage and military] road all the way up the right [west] bank of the Cowlitz to the mouth of the Toutle River (Hard-Bread’s) and thence deflecting northerly to the Chehalis, where the old and new routes were joined, and soon emerged into the gravelly prairies, where there were natural road beds everywhere. The facts are, this road, like Topsy, 'just growed,' and so gradually became a highway one could scarcely say when the trail ceased to be simply a trail and the road actually could be called a road. First only saddle trains could pass. On the back of a stiff jointed, hard trotting, slow walking, contrary mule, I was initiated into the secret depths of the mud holes of this trail. And such mud holes! It became a standing joke after the road was opened that a team would stall with an empty wagon going down hill" (Meeker, Pioneer Reminiscences).

Upon leaving the Kalama area, Meeker sent his wife and baby in a canoe up the Cowlitz River, assuming that would be an easier mode of travel. Meanwhile, he herded his two oxen up the east bank of the river, rejoining his wife at Hardbread’s, a hotel of sorts at the mouth of the Toutle River. Once reunited, the family prepared to head north overland: "But now we had fifty miles of land to travel before us, and over such a road! Words cannot describe that road, and so I will not try. One must have traveled it to fully comprehend what it meant" (Meeker, The Busy Life).

When Edward Jay Allen arrived in Olympia from Portland in late 1852, he wrote a letter to his family in Pittsburgh: "You will see from the heading of this letter that I have progressed 150 miles further, through the bowels of the land, which journey, when is taken into consideration the season in which it was undertaken, the length of time consumed, and the exposure and hardship it involved, may very properly be considered an extension of the Oregon Trail" (Johnson & Larsen).

John G. Parker co-owned an express business carrying money, mail, and other material south from Olympia. In late 1853, Parker described the Trail in a letter to Olympia’s Pioneer and Democrat. He was one of the few to portray the route from north to south.

"At the request of many persons who are desirous of knowing something about the state of the road, at this season of the year, between Olympia and Rainier [Oregon], we have deemed it proper to say a word on the subject through the column of your paper. As expressmen we are on the road regularly and ought to know something about it. It is, at present, in exceedingly bad order and the late freshet has even made it dangerous to strangers who travel the road without a thorough understanding of it. Let us take a slight glance at the road, in detail, from this point to Rainier.

"From Olympia to Skukum Chuck the road is in pretty good condition with the exception of the first mile from town and through the timber from Stony Prairie to Mr. Hodgison’s. There are several small creeks to cross before reaching Skukum Chuck, but all of them are fordable. As a general thing travelers ride as far as Judge Ford’s or Mr. Goodell’s the first day, and at either place they get well attended to. Skukum Chuck which is thirty miles from Olympia, and the Slough on the other side of it, are neither of them fordable. Indians however are encamped in the vicinity for the purpose of conveying travellers in their canoes and swimming horses, over both streams. Indian Prairie comes next, and then Wet Prairie which, one week ago, was covered with water to the depth of nearly three feet. Then you come to a creek or slough, over which you must swim your horse, and, after travelling four miles of bad road, through mud above your horse’s knees, you come out of the woods to Mr. Saunders’. Last year travellers avoided Wet Prairie and the slough by taking the 'Mountain Trail,' but now on account of the windfalls, that road is obstructed.

"Passing Mr. Saunders’ you come to the 'Burnt Woods,' where the road passes over a bottom of rich blue clay. This is one of the worst places – a horse sinks to his shoulder nearly every step. When over this part, three miles farther on brings you to the Nahwahkum, which is not fordable but across which you must swim your horse. Mr. Moore is building a good ferry boat here which he intends launching by the fifth of December next. The road from the Nahwahkum on past Jackson’s is in good travelling order to the Cowlitz Landing. At the Landing the traveller after spending a comfortable night at Powell’s, takes passage in a canoe to Rainier. The Cowlitz river is quite high. Messrs. Townsend & Moody run the mail canoe, which leaves the Landing regularly every Thursday morning at 7 o’clock and lands passengers at Rainier the same day in time for supper at Moody’s” [Parker, Colter & Co.].

The Trail Evolves

A stagecoach route was eventually established over the Cowlitz Trail/Military Road, although the coaches were often merely open farm wagons rather than the round-bellied purpose-built stages we know from Western movies. In the early 1870s, the Northern Pacific railroad tracks sutured their way through the Cowlitz Trail corridor from Kalama to Tacoma. As the railway progressed northward, the route of the stagecoaches shortened; who would ride in a bumpy open-air wagon when they could travel in relative comfort on a train?

After the railroad was completed, stagecoaches still serviced the area, but acted as feeders between the rail line and outlying towns to the east and west, rather than as north-south through-transportation. Soon, even these short stage lines were discontinued, as automobiles and trucks revolutionized travel in the early 1900s. Sections of the trail crossing particularly rough or swampy ground were planked or "corduroyed" with wood to provide a better driving surface.

By the early 1920s, an auto route roughly paralleling the old Cowlitz Trail route was created and named the Pacific Highway. Speeds of up to 35 mph were allowed. Circa 1926, the road was designated as US 99. In the mid- to late-1950s, the federal government surveyed a route for a modern freeway, soon known as Interstate 5. This route cut a vastly wider swath through Southwestern Washington than did the old roads; it was able to carry four, six, or more lanes of traffic as auto travel increased.

Repeating the evolution of the Trail from animal paths to a Native American route, modern roads also stitched together portions of the old Trail where feasible, and added straighter connections where required. On today’s travel corridor between the Columbia River and Puget Sound, surface traffic rushes along on the freeway, long freight and passenger trains roar by, and planes and jets buzz overhead. But beneath all this twenty-first century activity, rare pieces of yesteryear lie hidden: arrowheads, horseshoes, and rotted wood planking silently chronicle the past. Various bronze monuments mark the Cowlitz Trail’s historic location, and heritage groups are working to include the Trail in the National Historic Trails System. Native Americans, fur traders, non-indigenous settlers, and the military all contributed to the development and the legacy of the Cowlitz Trail.

Surviving Landmarks

Several landmarks from the Cowlitz Trail days survived for decades. Some still exist. The oldest apple tree in the Northwest was planted circa 1827 at Fort Vancouver, HBC’s trading post. The tree survived in a tiny public park until 2020; its offspring are now growing around the region. A black walnut tree on the southeast edge of present-day Longview is said to have been planted at the original site of Monticello, a very early pioneer town along the Cowlitz River. The tree survives to this day in a now-industrial area.

Circa 1860, Simon Plamondon and one of his sons built a small cabin out of cedar logs, north of present-day Castle Rock. The cabin still exists on private land. Plamondon was an HBC employee who arrived in the area in the early 1800s. His first wife was a member of the Cowlitz Tribe. Plamondon married twice more and fathered at least 10 children.

South of present-day Chehalis, John R. and Matilda Jackson lived on acreage known as The Highlands along the Cowlitz Trail. A cabin built circa 1851 still stands, although it has been refurbished twice, and little original material survives; it is now owned and managed by the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission. The cabin is known as the Jackson Courthouse, having served in that function in the 1850s.

The Joseph and Mary Borst home was built circa 1860 outside of Centralia, on the banks of the Skookumchuck River. Many travelers on the Cowlitz Trail visited this house. The home is now owned and maintained by the City of Centralia.

A log blockhouse was built in the Centralia area during the Treaty Wars of 1855-1856. The building was never used for defense purposes, but was instead used to store grain for the military. Although the blockhouse was moved twice, it now stands in a Centralia park near Interstate 5.

George Bush (ca. 1790-1863) and his wife Isabella Bush (ca. 1804-1866) established a homestead just south of present-day Tumwater. George was of African and Irish descent; Isabella was white. The Bushes brought butternut seeds with them over the Oregon Trail, and planted those seeds once they made their home along the Cowlitz Trail. At least one seed grew, and the resulting butternut tree stood until 2021, when it finally succumbed to old age. Thanks to the efforts of landowners and arborists, several offspring of the Bush Butternut are growing in public places.

Perhaps the most stunning survivor of Cowlitz Trail days is the blue camas (Camassia quamash), a wildflower that once blanketed the prairies along the Trail every spring. Native Americans used the bulbs for food, and cultivated camas by periodically burning prairies to manage invasive Douglas fir trees. Today, although South Puget Sound prairies are vastly diminished, camas manage to survive in protected pockets, where they add immeasurable beauty to the old Cowlitz Trail route.

The End of the Trail?

Many locations along the Oregon Trail and the Cowlitz Trail claim to be the "official" end of the trail: Oregon City, Portland, Astoria, Tumwater, and Olympia are among them. However, it’s been said that the end of the trail was wherever you ended your personal journey.