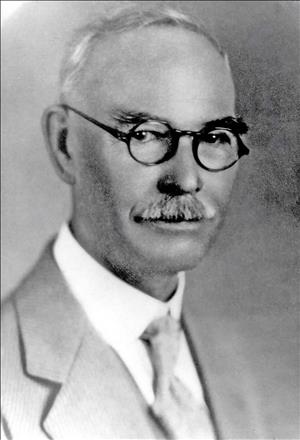

Perhaps no one in the early twentieth century brought more innovation and wide-ranging interests to the San Juan Islands than Dr. Victor J. Capron, who in his time there was a physician, farm owner, businessman, Friday Harbor town council member and mayor, state legislator, San Juan County health officer, state epidemiologist, and Washington State Board of Health member. After medical school and service as a government physician in Honolulu, Hawaii, Dr. Capron moved to San Juan Island to provide medical services at the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Company. Shortly thereafter he also opened an office in Friday Harbor. To have rapid communication between the two communities, he established the first telephone service on the island. He owned more than 1,000 acres of dairy, sheep, grain, and fruit farmland. Capron had a major interest in a creamery, town real estate, and the town lighting system. He and associates established the first hospital. He supported development of a water and sewer system for Friday Harbor and introduced important island-advantageous state legislation. Capron's first concern was always the betterment of life for island residents, and he was still available 24-hours-a-day for medical house calls just months before he died.

The Physician Forges a Career

Victor Capron spent his first decades on the East Coast, far from the islands in the Pacific Northwest between the Washington mainland and Vancouver Island that would become the center of his professional and home life. He was born in the village of Boonville, New York, to Smith (1840-1910) and Sarah (1842-1909) Capron. Victor Capron left the small community to enroll at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. He completed his degree and undertook three years of hospital medical practice at the Pennsylvania Hospital of Philadelphia and St. Luke's Hospital in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. After those years of preparation, Capron decided, like so many others, to move west for greater opportunities and new experiences. In 1890 he settled in then-booming Port Townsend, just across the Strait of Juan de Fuca from San Juan Island, but his plans to establish a successful practice there were soon discouraged when an unexpected and dramatic downturn in the town's economy forced him to consider other options.

In 1892 Capron moved even farther west, accepting a position with the Provisional Government of Hawaii in Honolulu. He loved living and working in the area and had the opportunity to study firsthand and become an expert on leprosy and many other infectious diseases. He hoped to stay on the island of Oahu, where he was briefly married to Augusta De Lion from Peru. However, an accident in which Capron was thrown from a horse and severely injured forced him into an extended recovery period. The citizens of Honolulu recognized the doctor's exceptional service and the quality of his medical care, naming a street (now on the grounds of the U.S. Army's Schofield Barracks Military Reservation) Capron Avenue in his honor. However, Capron in 1898 accepted an offer from John S. McMillin (1855-1936), owner of the Roche Harbor lime works on San Juan Island, where Capron had visited during his recuperation, to become the physician at the lime works. It was an association that lasted more than three decades.

Capron soon realized that trained medical aid on San Juan Island was minimal, and that there was need for a medical practice in Friday Harbor, the island's only town (population 400) and the county seat. By 1900 he had opened an office there and scheduled appointments one day a week, while being available for emergencies whenever and wherever they occurred within San Juan Island's approximately 55 square miles.

The distance from Roche Harbor to Friday Harbor was just under 10 miles across rolling, largely wooded terrain, and the time it took by horse or wagon to get from one community to another, or from Roche Harbor to southern outlying farms on primitive roads, was measured in multiple hours. If an accident should occur at the lime works while Capron was in Friday Harbor, for example, he might not get the news in time to arrive before it was too late. Deciding that this was unacceptable, Capron found a correspondence course in the new technology of telephony. He received permission from the county commissioners to string and operate telephone lines along the public roads. The editor of the local San Juan Islander (SJI) wrote that he hoped this would be just the beginning of a wider undertaking linking the major islands and the mainland. Beyond Capron's immediate concerns for his medical work, the editor thought that good telephone service "would enhance the value of all property in the county, would be of great assistance in all business enterprises, and would bring the farmers and orchardists into that close touch with the markets of the cities which is essential to the disposal of their products to best advantage" ("A Note ...").

Beginning in March 1900 with eight subscribers, the service expanded within a year to 33 subscribers receiving telephone service over 25 miles of line connecting most parts of the island. Much of the wire was not yet strung on poles but simply fastened to trees and fences. The cost for the new service was $2.50 per month, and the switchboard was initially located in Sweeney's Mercantile in Friday Harbor. In 1901 Capron asked the county commissioners to grant him an exclusive franchise to operate the telephone system in San Juan County for 30 years, but his petition was denied, as the county attorney opined that the commissioners did not have authority to grant such a request. Just a few years later a far more ambitious project was under discussion – a telephone line between Vancouver, B.C., and Bellingham on the mainland and Victoria on Vancouver Island, with the route to Victoria possibly by cable through the San Juan Islands. Capron and others operating telephone systems within the islands considered upgrading the local operations to enable a good interisland system and a joint venture with this proposed international endeavor with mainland connections.

A Man of Diverse Interests

Capron's personal life and interests were expanding in these years as well. In 1901 Capron married Fanny Kirk (1874-1956), daughter of Peter Kirk (1840-1916), founder of Kirkland in King County, who had a summer home, Deer Lodge, at Yacht Haven on the northwest side of San Juan Island. The young couple, who initially lived at Roche Harbor, soon began acquiring land, beginning with a large stock ranch at Mount Young (also known as Young Hill) near English Camp. Within the next decade they added another 240 acres near Sportsman's Lake for a sheep operation and acreage on the island's west side near Andrews Bay, with all the accompanying livestock and farm equipment, as well as property at Oakdale in the fertile West Valley and, for a time, a 1,000-acre tract on Cady Mountain. In 1904 Capron's parents arrived from New York to temporarily oversee the stock ranch at Mount Young. He ultimately owned 1,800 acres of land and operated three dairies and the sheep farm.

Capron also invested in town property and local businesses. He purchased the former county courthouse building and had it moved to a lot at Argyle and Spring streets, a major intersection in Friday Harbor, to be renovated for his medical practice. Capron and Peter Kirk bought majority stock in the Friday Harbor Lumber & Manufacturing Company with the intention of installing and operating an electric light plant that would finally make reliable electricity available to Friday Harbor residents, a service that had been elusive at best. Capron and R. R. Ramsden purchased the former Sweeney Mercantile properties on the waterfront as well as the Friday Harbor Creamery. When a fire burned the buildings to the ground in 1911, they were rebuilt and a warehouse added for storing grain, flour, and feed. Realizing by 1910 that the greater part of his time was being spent in Friday Harbor, Capron purchased a home there and moved his family, now including a daughter, Marjorie Kirk (1903-1972), and son, Victor James Kirk (1908-1986), to town. He continued to commute to Roche Harbor twice a week to serve the community there.

Always on the lookout for ways to make his work more efficient and provide better service for his patients and the community, Capron eagerly adopted the latest in technology and transportation, purchasing the second automobile on the island and commuting between Roche Harbor and Friday Harbor on the island's first motorcycle. In 1910 he purchased an early graphophone, a sound-recording device for use in business to allow dictation to be recorded and then played back. The following year Capron attended a meeting of the King County Medical Society and was introduced to X-ray technology for diagnosing fractures, dislocations, or tumors of the bones. Within a month, advertisements appeared in the local paper noting the availability in Capron's office of X-ray examinations. And because he so often had to make calls on patients in their homes scattered around the island, Capron developed a means of taking his X-ray equipment with him and using a small generator on the car's running board connected with a belt to the rear wheel of his car to run the apparatus wherever it was needed.

In 1911 it was announced that the county's first hospital would be opened in Capron's medical building at Argyle and Spring, with the newest equipment for surgery and modern electrical treatments as well as general medical practice. It would be staffed by Dr. Capron, Dr. Connor O. Reed (1882-1943) and "competent nurses ... in attendance to care for patients as efficiently as in the larger hospitals of the cities" and would initially have three private rooms and one ward with four beds ("Will Establish ..."). Newspaper articles announcing the new hospital noted what a boon it would be to islanders, especially when weather conditions made transport to the mainland for care difficult or impossible: "The simple fact that this refuge is assured must surely make us all healthier" (SJI, March 24, 1911).

Politics and Community Service

Capron arrived at Roche Harbor with a modestly liberal political outlook, but John McMillin, his employer and a staunch conservative, the most influential Republican on the island, soon persuaded him to adopt a largely altered viewpoint. Capron became an active member of the Republican Party. He was quickly involved in community affairs, serving on the Friday Harbor town council. In 1911 he was appointed to the committee investigating the development of a municipal water system and the optimal water source. Capron advocated strongly and successfully for Trout Lake as the best option. When, just weeks later, John L. Murray (1859-1949), Friday Harbor's mayor, decided not to run for reelection, there seemed "to be a very general desire among the businessmen and politicians [including Murray who had suggested him] for Dr. Capron as mayor. He is public spirited, independent and an active worker in the interests of the town" (SJI, September 15, 1911). Capron's platform included development of the municipal water and sewer systems, a lighting plant for consistent electrical service, and a reasonable payroll for town workers. He was elected with 128 votes out of 130 cast, serving from 1912 to 1914. Two decades later he was mayor again from 1930 to 1932.

Having had this first experience in public service and the opportunity to more generally and positively affect islanders' lives, Capron decided while still mayor to run for the state legislature. In 1912 he was chosen as the Republican candidate, defeating esteemed early island settler Charles McKay (1828-1918) by two votes, and easily won the general election. Arriving in Olympia for the first legislative session of 1913, Capron found himself appointed to eight committees including Dairy and Livestock and Memorials, Resolutions, and Petitions, both of which he chaired, along with Agriculture; Medicine, Surgery, Dentistry, and Hygiene; and others. The speaker of the state House of Representatives also selected Capron for a commission tasked with studying cooperative land mortgage banks and credit agencies in other countries and gathering information that might lead to innovative financing for Washington's agricultural development.

Early in the 1913 session, Capron introduced four bills. He withdrew one, concerning the transfer of excess monies from the fund for protection and propagation of game to the roads fund, in response to the indignant protests of his sportsmen constituents; the others were successful. The fourth bill became his single most important piece of legislation. Throughout the state citizens paid gasoline taxes and auto license fees that were placed in a fund to support the state highway system. But Capron noted that San Juan County had no state highways and drew up legislation stating that those taxes and fees should be returned to counties that were composed solely of islands. It passed and became known as the Capron Act. In 1925, Capron offered an amendment to his act, which passed. It provided that the monies collected be distributed to the island road districts on an assessed-valuation basis. In Friday Harbor, the street now named Warbass Way (in honor of another prominent early settler) was originally State Road, among the first paid for with funds procured through the Capron Act, which is still contributing to the island economy in 2024. Capron served in the state legislature from 1913 to 1917 and from 1923 to 1927.

In 1915 Capron began yet another public-service endeavor. He announced early in the year that he was withdrawing from the practice of medicine on the island and resigning his positions as mayor and San Juan County health officer because he had accepted a position with the Washington State Board of Health and was moving to Olympia. His letter published in the Friday Harbor Journal (FHJ) noted that for 15 years he had undertaken every call for assistance "and in so doing have formed many close ties and lasting friendships" and that his "residence will still be here [in Friday Harbor] and I trust will continue to be among the people whom I have learned to know and love" ("To Withdraw ...").

He served two years on the board of health and, in 1917, resigned and returned to the island to resume his medical practice. Shortly after his return to the island, Capron was asked to reassume the position of San Juan County health officer. He also served as the examining physician for the San Juan County draft board during World War I. He continued to occasionally take on additional tasks for the state, substituting briefly for the state commissioner of health and, in his role as state epidemiologist with special knowledge of infectious diseases, traveling to Bellingham to investigate a possible case of leprosy. In 1919 he was asked to once again fill a vacancy on the state board of health and was immediately appointed as assistant commissioner, prompting a move to Seattle for one year during which he maintained his ties to the island with frequent trips home.

Caring For and About the Community

When Capron returned to the island, his medical practice and many businesses and other activities were all in need of attention. He reestablished his medical practice in the front of the hospital building and was able to expand his offices there when a new hospital building, one touted as modern in every respect, opened elsewhere in Friday Harbor later in the year. He had taken time a few years earlier for a six-week post-graduate medical course in San Francisco and was soon busy again with grateful patients. By the end of his career, Capron had, for example, delivered more than 540 babies without a single loss of child or mother and handled medical conditions and traumas of almost every kind, even performing brain surgery in his hospital.

As in years past, he became active again in the local farmers' association, which he had helped found and served as chairman, as well as in the dairymen's association. Always interested in improved farming methods, he purchased a new International Harvester tractor, a 3-gang plow, and a double-disc harrow preparatory to putting in 300 acres of peas. However, by the late 1920s, now in his fifties, Capron had begun selling off much of his farm and ranch property.

He was frequently asked to speak at meetings on a variety of health-related and other topics. And he often wrote letters, always published on the front page of the Journal, on issues that he felt were important to the community. They included a note in 1926 concerning taxation issues especially related to farms and other tax rules that he felt were unfair and another about the health values of extending the water-system pipe at Trout Lake an additional 200 feet into deeper waters and converting to metal pipes from the old wooden ones. In 1930 he wrote a clear explanation and discussion about a proposed state constitutional amendment that would permit classification of property for taxation purposes – for instance, land would be classified differently from bank-account interest when tax rates were determined.

In 1925 he was among the early advocates for a ferry system. He spoke to the Commercial Club about the depreciation in farm property values that he attributed to inadequate transportation facilities and services, stating that if there were year-round interisland ferry service to the mainland, real-estate values would improve. He studied population statistics and concluded that the population was not growing because young people were leaving the island for more varied opportunities. He followed up with a letter to the Journal encouraging broader public support for a ferry system, declaring that without ferry service "San Juan County has moved back 150 miles into the backwoods" and that "If you want your children to live by you in your old age – work for a ferry. If you want your real estate to increase in value – work for a ferry" ("Capron Pleads ..."). He suggested that a ferry should make two round trips a day in the summer and one a day in the winter. He never stopped advocating for changes and services he felt would improve the life of the community.

Capron continuously strove to upgrade his medical skills, regularly attending state and regional medical meetings. He felt strongly that too many patients were being seen unnecessarily by specialists at large city clinics who were too ready to perform operations without clearly understanding the numerous possible negative outcomes. He advocated paying greater attention to determining the causes of diseases and their prevention and considering moderate approaches to treatment before more drastic ones. In the early 1930s Capron authored a short book titled Tragic Passing of the Family Physician that he said should "be considered in the light of a 'friendly critic'" (Tragic Passing ..., 5). In it he suggests "it is just possible that the specialists of a clinic often deceive themselves, as well as the patients, with regard to the importance of minor ailments, and suggest operations, knowing (subconsciously, perhaps) that the fee will be larger" and "because [surgery] is the most lucrative practice, it is the most dangerous" (Tragic Passing ..., 9, 18). He was convinced that being in a quiet, calm, familiar environment, usually one's own home, was, whenever possible and including for childbirth, preferable to hospitalization. He was in favor of treatments and diets being standardized throughout the medical profession and offered a series of sample diets with meals featuring many vegetables and fruits and lima-bean bread or muffins at almost every meal.

Capron was still seeing patients and making house calls in March 1934 when a fire of unknown origin broke out in his office. Both interior furnishings and equipment, which Capron valued at $500, were damaged by the fire and the water used to put it out. Six months later, Capron's daughter Marjorie found her father weak from loss of blood and incapacitated after suffering a severe nosebleed. He was taken to Bellingham for special treatment. On October 4 the Journal published a reassuring letter from him saying that he anticipated being able to come home in a few days. Doctors had, as part of his treatment, recommended that he have all his teeth pulled, which, apparently, he had done. Sadly, Capron was not doing as well as his optimistic note had suggested. By early November he was admitted to Virginia Mason Hospital in Seattle, where he died just three weeks later at the age of 66.

Tributes to the physician, farmer, community activist, and public servant poured in. The editor of the Journal noted that "In the death of Victor J. Capron, San Juan County lost a man to whom this county owes much in so many ways ... [He] always was progressive in thought and an ardent booster for any thing that would advance the interests of the community" (FHJ, November 22, 1934). In the files of the San Juan Historical Museum in Friday Harbor is one of Capron's Roche Harbor daybooks from 1900. Paperclipped to it is a faded typewritten note from an admirer identified only by initials: "We may sometimes live within the influence of a great man and fail to recognize his genius. The late Dr. V. J. Capron had much of genius and greatness in his character ... At the time of his passing -- the total of unpaid services would have made a small independence ... One of the San Juan's [sic] great men" (F.H.M.). So many islanders were indebted to him for his medical skills and compassion. In 1961 David Richardson, an islander and author of books and articles primarily on the Pacific Northwest, brought Capron to the attention of a new generation with a feature article in The Seattle Times magazine titled "Dr. Capron Epitomized the Family Physician," in which he recounted the doctor's notable career. Capron demonstrated a strong sense of service and devotion to civic betterment and is remembered for his outstanding legacy of personal, professional, and public accomplishment.