On January 17, 1916, the Skinner & Eddy Corporation begins construction of its first shipbuilding plant on the Seattle waterfront. Incorporated earlier in January, the company has been founded by five partners, including company namesakes David E. Skinner and John W. Eddy. Even before Plant No. 1 is finished, Skinner & Eddy receives an order for two $1 million cargo steamships from a Norwegian firm, followed by another contract for two oil tankers. Before long, the company will earn a reputation for its fast, efficient service, setting world production records. Just more than a year later, the U.S. will enter World War I, increasing the opportunity for lucrative government contracts. To cash in on the bonanza, the shipbuilders will purchase more land, hire more men, and increase production capacity. When the war ends in 1918, so too will the government's urgent need for ships. Skinner & Eddy will deliver its final ship – its 75th – in 1920 and the plant will close for good in 1923. In 1931, the former shipyard will become the site of Seattle's largest shanty town, known as Hooverville, which houses some 1,200 individuals during the Great Depression until it is demolished in 1941.

From Salt to Ships

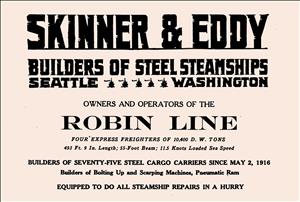

In January 1916, David E. "Ned" Skinner (1867-1933), John Whittemore Eddy (1872-1955), his brother James Garfield Eddy (1881-1964), C. B. Lamont, and L. B. Stedman formed the Skinner & Eddy Corporation, a shipbuilding company located on the Seattle waterfront at Atlantic Street and Railroad Avenue South, just south of Todd's original Seattle shipyard.

David Skinner and John Eddy, long-time business partners, came from similar backgrounds. Both were born in Michigan, were college-educated, began their careers as salt merchants, worked in the lumber industry, and then got into shipbuilding. Their early years in the salt trade taught them the ins and outs of running a business. Around 1900, they purchased the Hobbs-Wall Lumber Company in California and moved to San Francisco. In 1903, they moved to Puget Sound and bought the Port Blakely Mill on Bainbridge Island, turning it into the largest lumber mill in the world. Shipbuilding occupied the next stage of their careers.

Both men were enthusiastic big-game hunters. Eddy wrote many magazine articles on the subject as well as two books on hunting in Alaska. After a four-month-long safari to Africa in 1930, he returned with an elephant's head which was displayed in the Rainier Club in Seattle. From 1933-1942, he was a state legislator representing the 43rd Legislative District. Skinner went on to become president of the Metropolitan Building Company and invested in the fishing and canning industry in Alaska.

Streamlining Shipbuilding

Within weeks after incorporating, Skinner, Eddy, and their partners began constructing two frame buildings with adjacent structures called standing ways from which new ships would be launched. There was a reason for the rush: the company had promised delivery of four new vessels before August 1917. The first contract was for two steel cargo steamships for the Norwegian shipping giant B. Stolt-Nielsen; the second contract was for two oil tankers for Standard Oil Company. To ensure an on-time delivery, 200 additional men were hired, bringing the company's workforce to 700 in summer 1916.

Besides beefing up the number of workers, company executives had to do some logistical juggling as well. Steel to build the vessels was arriving at the rate of 1,000 tons a week and there was no time to lose:

"To expedite the delivery of the Standard Oil tankers, the plant yesterday began the construction of a third launching ways. The No. 1 ways will be vacated first, becoming available for one of the oil tankers when the first of the general cargo ships is launched in September. The second cargo ship will be launched in October. In the meantime No. 3 ways will be ready and work will have begun on the second tanker" ("New Shipyards to Add ...").

Skinner & Eddy's speed and efficiency were quickly apparent, and its first vessel, the steamship Niels Nielsen, was completed in September 1916. In remarks made that day, Capt. J. S. Gibson, president of the Water Front Employers' Union, noted:

"the organization and development of the Skinner-Eddy Corporation has no parallel in the history of the shipping industry, not only on the Pacific coast, but in all America ... Practically every bit of material entering into the construction of the Niels Nielsen had to be brought across the continent; then there was the problem of transportation, a most difficult one to handle ... It is also worthy of mention that the business experience of Mr. Skinner and Mr. Eddy, while of great magnitude in other lines of industry, did not embrace shipbuilding, but they had the brains to surround themselves with the best brains obtainable in the development of their gigantic enterprise" ("Launching Epoch …").

Seattle's Largest Shipyard

One of these "best brains" was David Rodgers (1864-1923), who was hired in 1916 as general manager. Born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, Rodgers started working in the shipyards when he was 8 years old and was apprenticed as a boat builder when he was 10. By the time he turned 21, he was on his way to America, carrying with him a reputation as one of the finest ship fitters in the world, a skill that "involved assembling, or 'fitting' together, a ship's structural steel – pieces such as the plates, bulkheads, and frames, typically by welding or riveting them together" ("David Rodgers …"). After stints in Duluth, Chicago, and San Francisco, Rodgers arrived in Puget Sound in 1900.

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the federal government moved quickly to strengthen its naval fleet, authorizing numerous contracts. To remain competitive, Skinner & Eddy hired more workers and purchased more land, which made them Seattle's largest shipyard. With more than 13,000 workers at its peak, the company smashed production records:

"The first record by the Skinner & Eddy Shipyard was set November 1, 1916, when the steel steamship West Haven, 8,800 tons, was turned out in sixty-four days. The record was cut to fifty-five working days from the keel laying with the launching of the 8,800-ton West Lianga in April 1917. Twelve days later it was delivered to the government, a world's record" ("Death Summons …").

Wartime contracts at Skinner & Eddy totaled more than $100 million, but according to Skinner, it was not about the money: "Never mind the money! A day's delay in finishing a ship is a crime against the boys in France!" ("Death Summons …"). Rodgers was deemed so essential to the war effort that President Woodrow Wilson invited him to the White House to personally thank him for his contributions.

When the war ended in 1918, government contracts dried up. Skinner & Eddy delivered its last ship in February 1920 and in 1923 closed its doors. In October 1931, an out-of-work homeless logger called Jesse Jackson, strolling by the empty lot, noted that the shipyard had "left behind concrete machinery pits plenty big enough to make a room, and plenty of scrap lumber and tin that could be used to build crude shelters, any of which would be a big improvement over the hard floors of the charitable institution" ("The Story of Hooverville …"). Within 30 days, the makeshift community had grown to nearly 100 shacks. Nicknamed Hooverville in a sarcastic nod to President Herbert Hoover, the encampment would house 1,200 individuals over the next decade. In 1941, city officials demolished Hooverville along with seven smaller encampments.