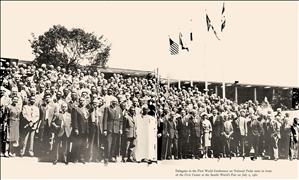

On June 30, 1962, delegates to the First World Conference on National Parks convene at Seattle's Olympic Hotel to begin a seven-day conference attended by hundreds of government officials and conservationists. The announced theme for the conference is simple and straightforward: "National parks are of international significance." The conference attracts important leaders, including the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, director of the National Park Service, and leading conservationists from every continent except Antarctica. Nearly as important as the meeting is the setting, which takes advantage of the Century 21 World’s Fair and nearby national parks, which delegates visit before and after the conference.

Separate From the Fair

The First World Conference on National Parks converged with Seattle’s Century 21 Exposition in the summer of 1962, although relatively little overlap occurred with the fair. The idea for the conference originated with Tsuyoshi Tamura (1890-1979), a landscape architect from Japan who was one of that nation’s leading founders of national parks. Tamura had proposed such a conference in 1958 at a meeting of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). IUCN took the lead as the principal sponsor and welcomed the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); the United National Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); the U.S. National Park Service; and the Natural Resources Council of America as other cosponsors.

The planners for the conference in Seattle intended it to foster better communication about national parks and encourage their spread worldwide. The conference also aimed to improve coordination among park administrators. The published proceedings declared the purpose of the conference as establishing "more effective international understanding and [encouraging] the national park movement on a worldwide basis" (Adams, xxxii). The conference brought these international concerns to Seattle, where American conservationists and park personnel could showcase their ideas with global leaders.

While the Century 21 Exposition celebrated the science and projected technological abundance into the future, the First World Conference on National Parks focused on protected areas where, instead, the natural world dominated. The two purposes did not seem to be entirely at odds. For example, Paul Thiry (1904-1993), the principal architect of the exposition grounds, also attended the parks conference, showing at least some shared sense of mission. Thiry was one of many local leaders who attended, including superintendents at Mount Rainier and Olympic national parks, professors, and activists in organizations such as the North Cascades Conservation Council and the Seattle Audubon Society. All told, the meeting attracted 145 delegates from 63 foreign countries and 117 delegates from the U.S.

Before the meetings started, delegates toured Mount Rainier National Park and Snoqualmie National Forest to properly set the mood. They stopped at Ricksecker Point, Narada Falls, and the gorge at Box Canyon. Such scenes lingered in delegates’ minds for several days while they shared ideas about protecting natural landscapes as far from the Cascade Mountains as Africa and Southeast Asia.

Greetings and Meetings

The official proceedings began the morning of Monday, July 2, when everyone convened at the The Playhouse on the World’s Fair grounds. Official greetings came from exposition officials, Seattle Mayor Gordon Clinton (1920-2011), and a representative standing in for Governor Albert D. Rosellini.

The director of the National Park Service, Conrad L. Wirth, offered an opening address. Wirth shared a broad history of conservation and parks, full of lessons from the American experience. "It is in the national parks that these influences on the United States can be maintained and kept pure, so that this and future generations may know and feel – and benefit from – the same wonderous [sic] exposure that our forefathers experienced," said Wirth (Adams, 14). Public interest in the outdoors was growing, and parks helped meet that need, even as they would take different forms depending on the unique experiences of each nation represented. Not surprising given the ongoing Cold War, Wirth praised the American parks as democratic. "National parks symbolize democracy in action," he said (Adams, 20).

As the opening address, Wirth’s speech established the American example as one worth emulating as delegates shared ideas the remaining week. At the time of the conference, the National Park Service was asserting its global leadership. The previous year, for example, the agency created a Division of International Affairs to coordinate global exchanges and, in effect, export the American national park idea. However prideful Wirth may have been, the conference gathered leaders and ideas from well beyond the nation’s borders.

After the opening statements, the conference relocated to the Olympic Hotel, where until Friday, July 6, delegates convened session after session where they summarized research and discussed key issues facing national parks and conservation around the world. These topics ranged from general principles of national parks to specific experiences in nations as diverse as Tanganyika or West Germany. Sessions addressed the economic and cultural values of parks, examined the challenges of coordination and administration, and probed emerging topics such as wilderness, endangered species, and transboundary issues. These conference sessions represented hard work and thorny problems with all delegates aiming to improve their management of protected areas worldwide.

One of the highlights came midway through the conference when Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall (1920-2010) delivered the keynote address, titled "Nature Islands for the World." Although the speech occurred in the middle of the conference, it captured the themes so well the editor of the official proceedings placed it as the opening section of the publication.

Secretary Udall noted the world’s fragility and worried about how materialism threatened nature. The presence of park advocates in Seattle encouraged him, however, helping him believe that not all people suffered from "a moral and spiritual sickness that results from being on the earth, yet not a part of it" (Adams, 4). Besides asserting his values, Udall called for concrete ideas, including a "Common Market of conservation knowledge and endeavor," where international experts could freely collaborate in global conservation efforts (Adams, 3). Capturing the enthusiasm of and hard work ahead for the delegates, Udall said, "We are the architects who must design the remaining temples; those who follow will have the mundane tasks of management and housekeeping" (Adams, 3). The comment fit the conference well, because both big ideas and necessary tasks were on the agenda.

After

The close of the conference came with 28 recommendations covering everything from concerns about population, the importance of continuing scientific research, and specific campaigns to protect specific animals such as rhinoceroses in Africa and the mountain tapir in the South American Andes.

With the First World Conference on National Parks concluded on Saturday, July 7, delegates dispersed. Yet some remained and continued to examine U.S. national parks. The first stop was Hurricane Ridge at Olympic National Park where "visitors enjoyed the widespread view of the Olympic Mountains and their many glaciers" (Adams, 387). Then, they headed to the Hoh Valley and the roadless ocean beach included in the park recently protected by local protesters.

Most delegates left after their excursion to the Olympic Peninsula. More than 60, though, boarded a train and headed to Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks in Wyoming, where they continued to study and debate national parks. Altogether, the conference and field trips, rooted in the Northwest, inspired the delegates to call for another international conference on national parks. The IUCN has sponsored global congresses on parks roughly every decade since the first successful and pivotal event in Seattle.