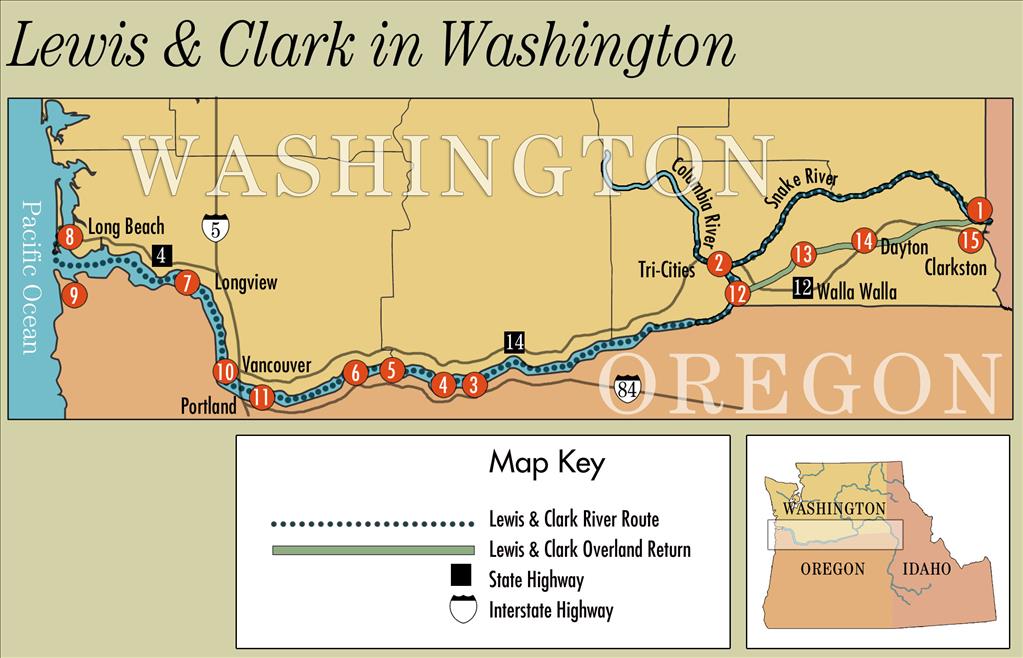

This tour of the route taken by Lewis and Clark through what is now Washington state was written by HistoryLink historian Cassandra Tate in 2004 and updated in 2024 by HistoryLink staff with new images and links to related content. The tour stops are numbered to correspond with the map above.

Daunting Conditions

When Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809), William Clark (1770-1838), and the Corps of Volunteers for Northwestern Discovery crossed into what is now the state of Washington in October 1805, they assumed that the worst part of their journey was behind them, expecting an easy float down the Columbia River to their objective, the Pacific Ocean. Instead, they found an unrelenting series of obstacles, dangers, and annoyances, from life-threatening rapids to inescapable fleas.

The rapids on the Columbia were much bigger and swifter than any they had encountered elsewhere. In the Columbia Gorge, warm air from the arid, treeless plains of eastern Washington collided with cooler air from the west, creating thermal winds of terrific force. Wood was scarce; any driftwood cast ashore by annual spring floods quickly vanished in the campfires of Indigenous people. Clark reported that people in one village were drying fish and prickly pears to burn as fuel in winter. On the lower Columbia, the challenges of the river were compounded by constant irritation from fleas, one legacy of the mild weather and the large population of dogs among the native people. At times, the men could get relief only by stripping naked and getting into the water.

Waterfowl flourished in the marshlands, bringing yet another aggravation. "I [s]lept but verry little last night for the noise Kept [up] dureing the whole of the night by the Swans, Geese, white & Grey Brant Ducks &c. on a Small Sand Island," Clark wrote at one point (using his distinctive spelling). "… they were emensely noumerous, and their noise horid."

The closer they got to the Pacific, the more they suffered. This ocean, Clark mused bitterly, was not "pacific" at all, but "tempestuous and horiable.” Storms pinned the party against the rugged, windswept northern coast for weeks. Waves slammed into the mouth of the Columbia with such force that some of the party got seasick. Their leather clothes rotted from the continual soakings, their supplies ran low, and they all got heartily sick of salmon.

It rained on the coast, drumming a cheerless note in Clark’s journal: "rained all the after part of last night, rain continues this morning … a cool wet raney morning … eleven days rain, and the most disagreeable time I have experenced …" Still, as the expedition prepared to leave its winter headquarters at Fort Clatsop, on the Oregon side of the Columbia, on March 23, 1806, his tone was conciliatory: "at this place we had wintered and remained from the 7th of Decr. 1805 to this day and have lived as well as we had any right to expect…not withstanding the repeeted fall of rain."

Two hundred years later, not much remains unchanged along the Lewis and Clark Trail in Washington. Many of the expedition’s campsites, along with the ancestral villages and fishing grounds of the Indigenous people they met, have been flooded by dams. The plains of Eastern Washington now bloom with orchards, vineyards, and other agriculture, the result of massive irrigation projects. From Clarkston to the coast, the Snake and Columbia Rivers, once muscled with white water, have been turned into a slackwater canal, carrying ocean-going barges more than 400 miles inland. Railroads and freeways slice through lands that once knew only Indian trails. But the wind still blows through the Columbia Gorge and the rain still falls on the Pacific Coast.

1. Confluence of the Clearwater and Snake, Clarkston

Traveling down the Clearwater River in five dugout canoes, the Lewis and Clark Expedition entered the present-day state of Washington on October 10, 1805, at the confluence of the Clearwater and the Snake rivers near Clarkston. The explorers camped at a site across the river from what is now the Clarkston Golf Course. The campsite itself, along with hundreds of other archeological sites, was flooded by the completion of Lower Granite Dam in 1975. The dam was the last in a series of eight that turned a segment of the Snake and Columbia Rivers into a huge slackwater canal, navigable by ocean-going barges.

Two Nez Perce men escorted the expedition to the confluence, part of a group that had provided critical aid when the explorers stumbled, exhausted and starving, out of the Bitterroot Mountains in late September 1805. The Nez Perce had lived, traveled, and hunted in the area for thousands of years; they knew the rivers and trails, and how to find food, water, and shelter. They shared this knowledge freely with Lewis and Clark, who later acknowledged the Nez Perce as among the most friendly and helpful of all the American Indian peoples they interacted with during their journey.

2. Confluence of Snake and Columbia rivers, Pasco

The explorers reached the confluence of the Snake and Columbia rivers at what is now Sacajawea State Park in Pasco on October 16, 1805. That night, a group of about 200 Yakima and Wanapam people from a nearby village entertained them with singing and drumming. Lewis responded with his standard speech of diplomacy, promising friendship and trade goods and expressing "joy in seeing those of our children around us."

Clark described this area as "one continued plain” with not a single tree to be seen anywhere. The native people helped them gather weeds and willow bushes for their campfires that night, but throughout their time on the Columbia Plateau, the explorers had difficulty finding wood. They gathered whatever driftwood they could find and were grateful for the occasional gifts of wood they received from native peoples. They sometimes bought wood, and at least once violated a self-imposed rule and stole wood that had been stockpiled at an Indian fishing site.

It was spawning season and the river was thick with salmon, but the men wanted red meat to eat. Lacking other game, they bought dogs from the native people. The Corps cut a wide swath through the dog population all along the Columbia. Most of the men, Clark excepted, didn't mind eating dog or horse meat, but they never learned to like fish.

3. Celilo Falls

Descending the Columbia, members of the Corps looked forward to an easy float down the river to the Pacific. Instead, they encountered the Columbia Gorge, a 55-mile stretch of the river that would prove to be by far the most dangerous part of their nautical adventures. The first obstacle was Celilo Falls, where the river dropped 38 feet in a short stretch of narrow cataracts. After scouting the waterfalls on October 22, 1805, the captains realized a portage would be necessary.

The men spent the next day carrying the canoes around the falls, then camped on a sandbar near the present-day town of Wishram. The ancient village of Wishram is now under the reservoir created by the Dalles dam in 1957. The village, near one of the most significant fisheries on the Columbia, was the site of a great Indigenous trade center. From east of the Cascade Mountains came the Cayuse, Nez Perce, and other nomadic peoples; from the west came the sedentary coastal and riverine tribes, led by the Chinook. They gathered at Wishram to fish, trade, socialize, and gamble. Overlooking Wishram was a petroglyph called Tsagagal ("She Who Watches"). A replica watches over tourists today at the Columbia Gorge Interpretive Center in Stevenson.

4. The Dalles

The expedition reached the head of the Dalles, in the vicinity of today's Columbia Hills Historic State Park, on October 24, 1805. Here, the Columbia squeezed through two sets of fierce rapids: the quarter-mile Short Narrows (which Clark described as an "agitated gut swelling, boiling & whorling in every direction"), and below that, the three-mile Long Narrows. The captains sent the non-swimmers and the most valuable cargo around by land, while the rest of the expedition shot the rapids in their heavy dugout canoes. They emerged safely, to the astonishment of the Indigenous people who gathered along the bluffs to watch.

Lewis and Clark were fortunate to encounter the Dalles on their downriver journey in the fall, when the water was low. Melting snow in the spring would have made the rapids impassable for even the most intrepid canoeists. "Dalles" is a French Canadian word for "flagstones" or "slabs," referring to the huge chunks of basalt that created the rapids. From this point onward, Lewis and Clark would see more and more evidence of European influence in the Pacific Northwest, from place names to Indigenous children with European fathers.

5. Cascades of the Columbia

The final nautical obstacle for the Corps on their voyage to the Pacific was the Cascade Rapids of the Columbia, near the site of today's Columbia Gorge Interpretive Center. A riverbend here led to four continuous miles of chutes, rapids, and falls. It took the expedition two days to get around them, at times hauling the canoes and cargo over an old Indian trail on the Washington side of the river. The trail came to be called the Cascades Portage. The trail became a roadway in 1850, then a railroad. But navigation on the river remained blocked until 1896, when, after 15 years and nearly $4 million, the Army Corps of Engineers completed the Cascade Locks.

6. Beacon Rock

Lewis and Clark first observed Beacon Rock while scouting the Cascade Rapids on October 31, 1805. Clark initially called it "Beaten Rock," perhaps because of its weathered appearance, but more likely because of his inventive spelling. Beacon Rock is one of only 13 geographic features in the Northwest that are still known by the names the explorers gave them.

The vent plug of an ancient volcano, Beacon Rock is more than 800 feet high, second in size only to Spain’s Rock of Gibraltar as a natural monolith. Henry J. Biddle, a descendant of Nicholas Biddle, the original editor of the Lewis and Clark journals, bought the rock in the 1850s in order to build a trail to the top. His heirs donated the site to the state of Washington in 1935, and today, it’s part of Beacon Rock State Park. The site is a few miles downstream from Bonneville Dam. Completed in 1937, it was the first of four multipurpose dams built by the Army Corps of Engineers on the lower Columbia. The dams were intended to control floods, provide irrigation water, generate electricity, and eliminate obstacles to navigation. They had unintended effects on the fish runs, reducing them to only a shadow of what they were when Lewis and Clark passed through.

7. Pillar Rock

On November 7, 1805, thinking he could see and hear the ocean in the distance, Clark wrote his most famous journal entry, again with his trademark spelling: "Great joy in camp we are in View of the Ocian, this great Pacific Octean which we have been So long anxious to See." In fact, the explorers were still more than 20 miles from the sea, and fierce storms, rolling waters, and high winds would keep them from their goal for more than one week.

They camped that night directly opposite Pillar Rock, which still juts out of the river, rising 75 to 100 feet above water level, depending on the tide, and still bears the name given to it by the explorers. The campsite is about 10 miles off Washington State Highway 4 on the Altoona-Pillar Rock Road. The Corps of Discovery was now deep into the coastal zone, with its frequent, steady rain punctuated by overcast days and chilly winds. Early joy at the apparent sighting of the ocean quickly dissipated. "We are all wet and disagreeable," Clark wrote, in one of his many variations on that theme.

8. Station Camp

On November 15, 1805 – one year, six months, and one day after leaving St. Louis – the Corps of Discovery reached the mouth of the Columbia. They established a temporary camp called Station Camp and spent 10 days exploring the area. From here, Clark and a group of men traveled to Cape Disappointment, a well-known anchorage site for trading ships. They hoped to replenish their supply of trade goods and send reports, specimens, and perhaps even a few men back to the United States by sea. However, there were no ships, and game was scarce on the windswept northern side of the river. On November 24, the captains asked members of the expedition to vote on a site for a permanent winter camp. Everyone participated, including Clark’s slave York and Sacagawea, their guide. The tally was 30 to 2 in favor of crossing the river into what is now Oregon.

Station Camp is commemorated today by a chainsaw sculpture of Lewis and Clark in the Lewis and Clark Campsite State Park, a roadside attraction on Highway 101 about two miles west of the Astoria-Megler Bridge.

9. Fort Clatsop

Fort Clatsop, the first American military establishment to be built in the Pacific Northwest, was located in a thickly wooded site about five miles south of present-day Astoria, Oregon. It consisted of seven cabins enclosed by a stockade. The men slapped it together in just 15 days; named it after their nearest neighbors, the Clatsop Tribe, and settled in for what was to be a sodden, dreary winter.

The fort was occupied from December 25, 1805, to March 23, 1806. The Corps spent that time hunting, making moccasins and other clothing, and boiling seawater to get salt for the return trip. Once they took a short trip to see a beached whale and Sacagawea went along. The captains worked on their journals, making extensive notes about the language, dress, and customs of the coastal Indians, who they found "assumeing and disagreeable" and "much inclined to venery" from contact with white fur traders. It rained through it all, which made a steady drumbeat of complaint in the journals.

Forces of nature reclaimed the hastily-built fort quickly after the expedition left, but a reproduction was constructed in 1955 by citizens and organizations of Clatsop County to mark the 150-year anniversary of the expedition; that burned down in 2005, but was rebuilt in 2006.

10. Cathlapotle Village

Cathlapotle Village, also transcribed as Quathlahpotle, was a large settlement of 14 wooden plankhouses in what is now the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge. Lewis and Clark camped near here on their westbound journey on November 5, 1805, and again returning home on March 29, 1806. The village had been occupied for more than 350 years and had an estimated 900 residents when the explorers passed through. The population was decimated by epidemics of influenza and other diseases a few decades later, and the village was abandoned. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service erected a replica of a plankhouse in the general area of the former village in 2005.

Both captains made detailed observations about the Quathlahpotle, a Chinook-language people. Lewis was impressed by their four-foot-long iron scimitars, which he described as "a formidable weapon." He noted that the people were "fond of sculpture," had plentiful supplies of sturgeon and anchovies, and were eager to trade for wappato, a potato-like root. The village was in a stretch of the Columbia that was densely populated by native peoples. Today, the region, encompassing Vancouver and Portland, is the most urbanized area on the Lewis and Clark Trail west of the Continental Divide.

11. Washougal

Lewis and Clark had intended to spend just one night at the mouth of the Washougal River as they hurried up the Columbia on their voyage home. They ended up staying from March 31 to April 6, 1806. What they called Provision Camp was their second-longest encampment in present-day Washington. The site was at a popular river gathering point for the WaSucally and other Chinook Indians. Salmon as well as deer, elk, and bear were plentiful, along with wappato and camas bulbs. From the Chinook the explorers learned about the existence of the Willamette River, a major tributary of the Columbia that Clark named the Multnomah. They also heard reports about a scarcity of food in the region to the east, where the spring salmon had not yet returned.

From their camp, located in the vicinity of today's Steamboat Landing Park in Washougal, the men hunted, made clothing, and dried meat that they hoped would help sustain them until they reached the Nez Perce homelands in Idaho. Meanwhile, Clark and a small party explored the Willamette, traveling upstream about 10 miles.

12-13. Touchet River Campsite

Following the advice they received at Wallula, Lewis and Clark cut through southeastern Washington on a well-traveled trail that had been used by indigenous people for thousands of years. The same road was used later by Hudson's Bay Company employees, early miners, and army expeditions. Today, traces of it can still be seen from the Touchet River near the Lewis and Clark campsite of April 30, 1806. Lewis described this small river as "a bold Creek." It was a pleasant place to camp, with "an abundance of wood for the purpose of making ourselves comfortable fires," a relief after the treeless plains of the Columbia Plateau. A modest roadside sign marks the site, seven miles south of Highway 124, on a smooth two-lane road.

14. Dayton

By the time the explorers reached present-day Dayton on May 2, 1806, they had exhausted the supplies of food accumulated during their stay at Provision Camp near Washougal. Lewis saw two deer at a tantalizing distance, but the hunters were only able to kill one duck. Three Walla Walla people accompanying the party showed them how to eat cow parsnips, removing the toxic outer layer of the stem to reveal the succulent, tasty inner stem. Lewis reported that he found the plant "agreeable" and could "eat heartily of it without feeling any inconvenience." The campsite is located in the vicinity of the Lewis and Clark Trail State Park, just west of Dayton. The explorers noted that there was "more timber than usual" on the nearby creek (a tributary of the Touchet River). The site today is still heavily wooded, a welcome refuge from the surrounding plains.

15. Alopwai Interpretive Center

On the morning of May 4, 1806, the explorers stopped for breakfast at a Nez Perce village of six families on the Snake River near what is now the Alopwai Interpretive Center in Chief Timothy State Park, about eight miles west of Clarkston. Among the village's later residents was a child named Tamootsin (also spelled Timootsin), who grew up to become Chief Timothy (1808-1891), a stalwart supporter of white settlers in the 1860s and one of the first Nez Perce chiefs to convert to Christianity. Lewis and Clark described the village as "miserably poor." They bought two very lean dogs from the inhabitants and pressed on. That evening, they camped at a site on the Snake River in Whitman County, some three miles below Clarkston. The next day, they left the confines of Washington and "proceeded on" into Idaho.