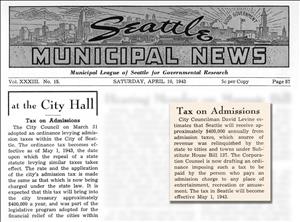

On May 1, 1943, an admission tax on theaters and other entertainment venues goes into effect in Seattle. City officials estimate the tax will bring in about $350,000 during its first year. Known initially as the entertainment or amusement tax, it is first levied by the state in the 1930s until taxing authority is shifted to the cities a decade later. In 1969, the admission tax will increase from 3 percent to 5 percent, added to the full admission charge. Some of the organizations exempt from the admission tax in 2024 include nonprofit resident arts groups, cultural and historic organizations, music venues seating fewer than 1,000 people, museums, the aquarium, and the zoo. Commercial events requiring a ticket, such as rock concerts, movies, and carnivals, are subject to the tax. Seattle’s Office of Arts & Culture, established in 1971 as the Seattle Arts Commission, receives much of its funding from the admission tax to support office operating costs, grant programs, and arts education.

Raising Revenues and Tempers

Washington’s entertainment or admission tax was first levied by the state in the 1930s until the ability to charge an admission tax was shifted to municipal governments a decade later. On April 30, 1943, seeking to raise funds to counter a growing deficit, Seattle officials passed an admission tax on "theaters, dances, cabarets, plays, sports, etc., at the same 5% rate they have been taxed by the state. The city tax will become effective May 1, 1943, at which date the state admissions tax will be lifted" ("40 New Members …"). Projected to raise about $350,000 the first year, the tax was more successful than expected. Within a year, "income from the theater admissions tax, which the state last year surrendered to the city as a source of revenue, produced $299,454 the first half of 1944, indicating a total of $596,504 for the year" ("City’s Income Up $500,000").

In the late 1950s, a tax amounting to one cent on every 20 cents of the ticket price was levied on all forms of entertainment except for performances by school groups. This was changed in 1958 when the Seattle City Council unanimously approved a new formula to "benefit movie theaters and many worthwhile community activities" ("City Movie Tax Slashed by Council"). Under the new rate, the first 50 cents of admission were tax-free; anything over 50 cents was taxed at the rate of 3.5 percent. A variety of organizations were expected to benefit from the change, including the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, Children’s Orthopedic Hospital, museums, and church groups.

Requests for exemptions, special treatment, even lawsuits, occurred occasionally. In 1962, a lawsuit was brought against the city by Air-Mac Industries Inc., the pedicab concessionaire for the World’s Fair, to stop the city from enforcing the admission tax on its human-powered vehicles. The following year, when the Ice Capades was scheduled to present a show at Seattle Center, the event organizer requested that the Center Arena be classified as a theater, thus qualifying them for the lower tax rate enjoyed by theaters. In response, city councilmembers raised the tax to a flat 3 percent of the full ticket price.

In 1970, the 3 percent tax was upped to 5 percent. A few years later, when bowling alley owners were required to charge the 5 percent admission tax, the industry pushed back. An ad appearing on December 26, 1974, in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer called on voters to oppose the new referendum: "The Seattle City Council voted in a new 5% tax on bowling. It is called an admissions tax and is in addition to the 5.3% sales tax already being paid on bowling. This means bowling will be assessed a total of 10.3% in taxes! This grossly unfair new tax on your bowling recreation could lead into more such bad taxation! Where does it all end?" ("Please Help!!").

"Penny Wise, Pound Foolish"

Although the increase from 3 percent to 5 percent was forecast to bring in an additional $380,000 annually, it also raised the hackles of many a politician and arts lover. Former state legislator R. Mort Frayn (1906-1993), running for Seattle mayor in 1969, spoke out against the rate hike, calling it "a case of penny wise, pound foolish ... Most cities recognize that cultural attractions are important not only to the tone and quality of urban life but to overall economic health" ("Frayn Would Limit Boost in Admissions Tax"). Arts enthusiast Mrs. George A. Schairer, a trustee of the Seattle Opera Association, outlined her opposition in a letter to the editor: "It seems ridiculous that the opera, the symphony, and the Repertory Theater should be penalized by the application of this tax ... These organizations run a deficit operation dependent upon the generosity of patrons and contributors for their very existence, yet they contribute so much to the cultural enrichment and civic pride of our city" ("Major-League Obstacle Cleared").

Allied Arts, founded in 1954 by a group of individuals dedicated to advocating for Seattle arts and urban design, championed a proposal to repeal the admission tax on resident nonprofit performing-arts groups and replace it with a hotel and entertainment tax. "This shifted the tax burden from struggling arts groups, placing it on the businesses that relied on visitors that enjoyed local arts. Mayor Wes Uhlman declared his support for Allied Arts’ idea" ("Seattle Arts Commission/Office of Arts & Culture").

The distinction between resident nonprofit arts groups versus commercial entertainment continued to evolve. In 1991, the blockbuster musical Les Miserables, staged at the nonprofit 5th Avenue Theatre, "grossed a reported $5 million and left, with city government getting not a penny. City planners, scrambling for new revenue sources in the face of a $29 million general-fund deficit, don't intend to let that happen again. The amendment is intended to make promoters presenting commercial productions in Seattle pay the city a 5 percent tax on the price of admission, even if the production is at a non-profit theater" ("Arts Leaders Maneuvering ..."). In 1992, revenue from the admission tax brought in $2.4 million. That increased to $5.3 million in 1995 and $9.7 million in 1997.

In 2017, admission tax funds helped Seattle’s Office of Arts & Culture support more than 375 artists and cultural organizations who created more than 3,600 performances, events, and exhibit days, reaching an estimated 1.7 million people. In 2019, the admission tax raised more than $11 million. When the pandemic hit in March 2020, forcing theaters, arenas, and other venues to close, admission tax receipts declined by nearly 90 percent. In 2024, as the city recovered from COVID-19 and attendance at events approached pre-pandemic levels, revenues from the city’s admission tax climbed as well.