Dr. William F. Tolmie played a significant role in the Puget Sound region as it came under United States jurisdiction and Washington Territory was created. A young Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) clerk and surgeon, Tolmie participated in the 1833 establishment of Fort Nisqually (in present-day DuPont), the first non-Native settlement on Puget Sound. During his early years in the Northwest Tolmie kept extensive journals describing the region's land, peoples, and cultures. He collected plant and animal specimens and cultural artifacts for scientists in England. He returned to Fort Nisqually in 1843, taking charge as it transitioned from fur-trading outpost to center of extensive farming operations under HBC subsidiary Puget Sound Agricultural Company (PSAC). Tolmie followed the British company's policy of friendly, cooperative relations with Native tribes and attempted the same with the growing number of American settlers. This proved increasingly difficult as settlers encroached on company farmlands and American efforts to confine tribes on small reservations led to war in 1855-1856, with Tolmie and HBC caught in the middle. In 1859, with PSAC transferring more operations from American territory to Vancouver Island, Tolmie moved to Victoria, where he took charge of PSAC farms on the island.

From Scotland to the Northwest

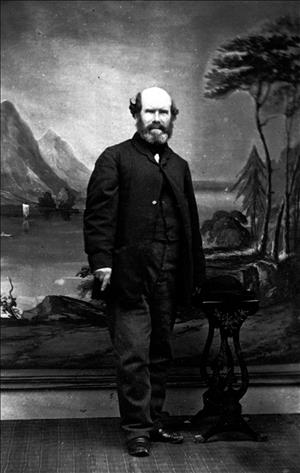

William Fraser Tolmie was born in Inverness, Scotland, on February 3, 1812, the first of two children of Alexander and Marjory Fraser Tolmie. His mother died when he was 3, and he and his younger brother spent some years in the custody of a strict aunt. An uncle (not married to that aunt) who practiced medicine inspired his interest in the field. Recognizing his interest and academic ability, Dr. James Tolmie encouraged William to study medicine at the University of Glasgow. He did so from 1829 through 1831, earning a diploma in medicine at age 19. It wasn't an MD, but by the standards of the time qualified him as a surgeon. Although medical practice was a small part of his career, he was known throughout his life as Dr. Tolmie.

Tolmie's life was strongly influenced by two professors. Botany professor William J. Hooker (1785-1865) had mentored other naturalists who played important roles in Pacific Northwest history, including David Douglas (1799-1834) and John Scouler (1804-1871). Hooker's classes and example encouraged Tolmie's lifelong passion for "botanizing," which he enjoyed in Scotland even before traveling to North America. Scouler, professor of mineralogy and natural history, was surgeon on the Hudson's Bay Company ship that carried Douglas to the Northwest in 1825. There Scouler collected plants and Native American artifacts and his stories piqued Tolmie's interest. In the summer of 1832 HBC was looking for medical officers for its Columbia District and sought advice from Hooker, who recommended Tolmie.

That September Tolmie signed a five-year contract as a Hudson's Bay Company clerk and surgeon and embarked on the seven-month-long journey to the Columbia. Tolmie chronicled the journey in the diary he'd begun as a medical student – its first entry, for October 8, 1830, included the note that he "Called on Doctor Hooker" (Journals, 11). Tolmie recorded his first years in the Northwest in considerable detail, and the May-December 1833 entries provide one of the earliest substantial accounts of the land, peoples, and cultures of the Columbia River and Puget Sound. After rounding Cape Horn, the ship stopped in Hawaii, where Tolmie made several plant-collecting excursions.

On May 4, 1833, Tolmie arrived at HBC's Fort Vancouver on the north bank of the Columbia, headquarters of the company's Columbia District. Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin (1784-1857) informed Tolmie he would be stationed at a new fort on Milbanke Sound in what is now British Columbia. Tolmie spent two weeks at Fort Vancouver, treating patients and collecting plant, bird, and animal specimens. He planted dahlia seeds and gave McLoughlin acacia seeds collected on Oahu – early introductions of both species to the Northwest.

Fort Nisqually, Mount Rainier, and Northward

Tolmie began the journey north by traveling overland with Chief Trader Archibald McDonald (1790-1853) via the Cowlitz Trail to the site McDonald had selected for HBC's Fort Nisqually, the first non-Native settlement on Puget Sound. It was at a Nisqually Indian village at the mouth of Sequalitchew Creek near the Nisqually Delta, which they reached on May 30. Above the beach, where the village and a temporary HBC storehouse were located, oak prairies on the bluffs extended for miles on both sides of Sequalitchew Creek's deep ravine. Tolmie explored nearby prairies with McDonald as the chief trader determined where to locate the fort.

The plan for Tolmie to continue onward to Milbanke Sound changed after Pierre Charles, head of the fort's building crew, seriously injured his foot with an axe. Charles's need for ongoing treatment (he eventually recovered), combined with McDonald having to leave for another assignment before his successor as Chief Trader at Fort Nisqually arrived, led to Tolmie staying at Nisqually another six months. Until new Chief Trader Francis Heron (1794-1840) arrived, and several times while Heron was away later, along with his other duties Tolmie oversaw the post's busy fur trade.

Tolmie became friends with village chief La-ha-let (also spelled "Lachalet," d. ca. 1849), considered the main leader of the Nisqually people living on the delta and up the river. Tolmie noted he "got from Lachalet a copious vocabulary" of the Nisqually language (Journals, 227), to which he regularly added, eventually learning to speak Lushootseed. Tolmie relied on La-ha-let not only for "information on Indian affairs," but also for insights into local birds, fish, and animals (Carpenter, 52).

La-ha-let was Tolmie's guide on a 10-day "botanizing excursion to Mt. Rainier" (Journals, 230). With La-ha-let's nephew and two Puyallup Indians, they traveled by horse to the Puyallup River and aways up it, then by foot toward the river's headwaters near Mowich Lake. Tolmie and some of his companions twice ascended a peak whose summit, that September, "was ancle [sic] deep with snow" (Journals, 232). Tolmie collected plants at the snow line and made detailed notes of his observations of Rainier's volcanic summit, including glaciers on it. His excursion was the first exploration of Mount Rainier by a non-Native, and his account is the earliest-known description of glaciers in the continental United States.

Tolmie remained at Fort Nisqually that fall, taking charge while Heron was away and packing some of his specimens for shipment to England. In December 1833 he sailed to Campbell Island on Milbanke Sound, where the Hudson's Bay Company had recently established Fort McLoughlin. He spent the next two years in the future British Columbia, much of it at Fort McLoughlin. For five months in 1834 he traveled farther north, accompanying Chief Trader Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854) as he moved Fort Simpson on the Nass River to a new location and negotiated unsuccessfully with Russian authorities for access to Russian territory in what is now the Alaska panhandle.

Fort Vancouver, Medical Travels, Extensive Collections

In early 1836 Tolmie traveled back to Fort Vancouver. There he first met 9-year-old Jane Work (1827-1880), whom he would marry 14 years later. She was the oldest child of Irish-born HBC trader John Work (ca. 1792-1861) and Josette Legacé Work (1809-1896), daughter of a Spokane Indian woman and a French Canadian voyageur. John Work had recently taken charge of Fort Simpson – Tolmie met him briefly at Fort McLoughlin, describing him as "a well informed old gentleman" (Journals, 303). Josette Work and their children stayed at Fort Vancouver until late 1836, when she took the younger children with her to Fort Simpson, leaving Jane and her 7-year-old sister Sarah (1829-1906) in school at Fort Vancouver.

Tolmie took on a protective role for the two Work sisters who remained at Fort Vancouver. HBC officials determined in 1838 that schoolmaster John Fisher Robinson was sexually abusing female students. Families, including the Works, transferred their children from Fort Vancouver to a school at the American Methodist Mission on the Willamette River. Tolmie wrote the missionaries on behalf of "Mr. Work," asking if they "could receive into your family as boarders the two Miss Works" (Journals, 332-33); not long afterward he requested they send Jane back temporarily for the investigation into Robinson's conduct. The schoolmaster was found culpable, flogged publicly, and fired.

Tolmie's detailed journaling ended before his return to Fort Vancouver, likely due to his increasing responsibilities for trade and medical practice. His entries were now mostly letter drafts, notes, and lists. Some letters, along with lists of specimens and other collections sent home, reflect his ongoing interest in local flora and fauna and Indigenous cultures. In October 1836 he wrote a friend in Scotland that "Since coming to this country there are two things which in my botanical pursuits give me frequent cause of regret – the first is not having seen the poor deceased Douglas" (Journals, 321). Douglas, whose earlier trips and discoveries were a major inspiration for Tolmie, was in the Northwest when Tolmie arrived in 1833. Although Tolmie's journal several times expressed hope they would meet, that didn't happen before Douglas departed for Hawaii, where he died in 1834. (Tolmie's other regret was also missing naturalist Thomas Nuttall [1786-1859].)

While at Fort Vancouver, Tolmie traveled to other HBC posts when medical assistance was needed, including at least two trips to Fort Nisqually. In late 1836 he treated Chief Factor Duncan Finlayson (ca. 1796-1862) there. He returned the following spring in response to a major outbreak of "intermittent fever" (probably malaria). Indigenous inhabitants of the Northwest had very limited immunity to diseases introduced by traders from Europe and the U.S. in the early 1800s, and several epidemics of intermittent fever, smallpox, and other introduced diseases had devastated populations along the Columbia. Intermittent fever reached Nisqually in 1836 and returned in early 1837. Indigenous peoples around the region sought care at the fort, and children of employees, most with Indigenous heritage, also became sick. While at Nisqually, in addition to treating intermittent fever Tolmie began a program of inoculating the south Puget Sound tribes against smallpox.

Tolmie completed his five-year contract in 1837, but with no replacement then available, remained at Fort Vancouver another four years. During that time he sent multiple boxes of items he'd collected to destinations in Scotland and England, including the museum in his hometown of Inverness and his former professors Hooker and Scouler, as well as to HBC officials. The shipments included plant and animal specimens, along with cultural artifacts such as clothing, pipes, fishhooks, masks, and blankets, that Tolmie was given or purchased from their makers or owners. They also included human skulls, taken without consent and in gross violation of Indigenous customs and beliefs. Tolmie was one of many early naturalists in the Northwest, including Scouler, who collected human remains – David Douglas was a notable exception. At the time scientists in Europe and the U.S. considered collection and study of human remains, especially skulls, from different peoples around the world essential to the newly emerging science of anthropology. Native American remains in particular were collected in large numbers, with consequences still being felt two centuries later.

From Furs to Farms

By the late 1830s, the profitability of HBC's Northwest fur business was declining. This was due partly, Tolmie noted, to "depreciation in the value of Beaver, occasioned by improvements in the manufacture of Silk Hats; but chiefly, to diminished Returns; caused by the exterminating system of hunting pursued" (Journals, 334). In response, and to strengthen British claims to the Northwest as American settlement increased, HBC organized the Puget Sound Agricultural Company as a subsidiary to conduct farm and livestock operations. Cowlitz Farm was established at the start of the Cowlitz Trail portage, and plans were made to transfer Fort Nisqually, where farming and especially ranching (for which the rocky soils were more suitable than largescale field crops) were already expanding, to PSAC. At the same time, Tolmie had become increasingly involved in agricultural work at Fort Vancouver and in the nearby Willamette Valley, where American settlers and some former HBC employees were establishing farms.

Tolmie began his trip home in March 1841. He traveled with the company "express" over the Canadian Rockies to York Factory on Hudson Bay, from where he sailed to London. He arrived in October and spent the next year in Europe, visiting family and friends in Scotland and England and pursuing additional medical studies for several months in Paris. He also studied Spanish, expecting his next assignment would be at the Hudson's Bay Company post in Yerba Buena (now San Francisco), then part of Mexico.

It turned out the company had other plans, inspired at least in part by Tolmie's conversations with officials at HBC's London headquarters. Two months after he departed on the HBC ship Columbia for the long trip around Cape Horn to the Northwest, headquarters sent orders to John McLaughlin that Tolmie be stationed at Nisqually as medical officer, Indian trader, and superintendent of PSAC farming operations. The letter stated that "[w]hile Dr. Tolmie was here, we had much conversation with him on the subject of farming, to which he seems to have given a good deal of attention" (Carpenter, 120). The orders reached Fort Vancouver shortly after Tolmie arrived in May 1843, and the 31-year-old soon headed on to Nisqually, where he would preside for the next 16 years.

Tolmie's first order of business was to oversee the relocation and expansion of Fort Nisqually for its role in PSAC's agricultural operations. The "New Fort," about a mile east of the original fort, was located on the southern bank of Sequalitchew Creek before the deep ravine through which it runs its final mile, closer to accessible fresh water and among fields already under cultivation. Several buildings from the "Old Fort" were dismantled and rebuilt at the new location, and additional buildings, many housing animals and farm products, were constructed over several years. Farming operations increased dramatically during Tolmie's early years in charge. Nearly 6,000 sheep and more than 2,000 cattle were reported by 1845; the number of sheep, whose wool was shipped to England, would double by 1849. Horses, oxen, and pigs also increased, as did crops raised. Animal products and grain were shipped to markets including Alaska, San Francisco, and Hawaii. Besides expanding the fort itself, Tolmie established additional small farms, or "outstations," across the prairies between the Nisqually and Puyallup rivers and up into the Cascade foothills.

American Settlers and Government Arrive

As farmwork increased, so did the number of company employees at Fort Nisqually, from just six or seven to 17 in 1845 and nearly twice that a year later. There were also increasing numbers of Indigenous "day workers," some hired seasonally but others employed year-round. Like La-ha-let in the fort's earliest days, prominent Nisqually leaders were among those who assisted operations and developed close ties to Tolmie, notably half-brothers Leschi (1808-1858) and Quiemuth (ca. 1798-1856), who helped manage PSAC herds. As dependent on local Indigenous communities as when they provided the furs, PSAC and Tolmie continued the company policy of maintaining good relations with those communities.

They followed a similar policy of cooperation when American settlers began to arrive. American missionaries had established a Methodist mission house near Fort Nisqually in 1839 with HBC assistance, but closed it in 1842. Permanent American settlement on Puget Sound began in 1845, when a party led by George Bush (1790?-1863) and Michael T. Simmons (1814-1867) settled along the Deschutes River, where they established New Market (now Tumwater), some 15 miles southwest of Nisqually. Tolmie provided the newcomers food and supplies on credit, some of which they repaid by cutting shingles for Fort Nisqually.

For a time, PSAC remained the dominant non-Indigenous presence north of the Columbia. British as well as American citizens had organized a provisional government of Oregon, which in 1845 created Lewis County, covering the area north of the Columbia. In June 1846 Tolmie was elected as the new county's first representative in the provisional legislature. However, a major turning point came that same month, when Britain and the U.S. settled their competing claims to the Northwest by agreeing on the 49th parallel as the international boundary. HBC officials had hoped that the boundary would follow the course of the Columbia River, leaving much of what is now Washington in British hands. Instead, HBC and PSAC lands around Fort Vancouver, Cowlitz Farm, and Fort Nisqually and its outstations were now all under American jurisdiction and the company concentrated on its holdings north of the 49th parallel and on Vancouver Island (which the treaty gave entirely to Britain), where Fort Victoria became the regional headquarters. Although the treaty provided that the rights of HBC and PSAC to land they occupied in American territory would be respected until the U.S. government paid a mutually agreed price for it, protecting company land and livestock from encroaching American settlers became a major challenge for Tolmie.

In 1847, the year he was named Chief Trader, Tolmie noted in the fort journal that Americans were arriving "daily in good numbers to 'have a look at the Country'" (Ficken, 7). Formal American jurisdiction soon followed. In 1848 Congress established Oregon Territory, initially encompassing all of what is now Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming. Most of the American population was still south of the Columbia but territorial courts and the U.S. Army arrived on Puget Sound the next year, in response to an incident at Fort Nisqually.

On May 1, 1849, a large group of heavily armed Snoqualmie Indians arrived at Nisqually, having heard that a son of La-ha-let was mistreating his wife, the daughter of a Snoqualmie chief. Fort officials attempted to negotiate the dispute while also summoning employees and visitors inside and closing the gates. But shooting broke out, apparently triggered by a fort guard who fired a gun "in jest" (Carpenter, 144). Two Americans who had not heeded the call to come inside were caught in the crossfire and one, Leander Wallace, was killed.

In response to Wallace's death, Oregon Territorial Governor Joseph D. Lane (1801-1881) requested that the U.S. Army, which had just established its first Northwest base, Camp Columbia, near HBC's Fort Vancouver, locate a fort on Puget Sound to protect Americans there. Lane sent Tolmie a message to translate and present to local tribes explaining the Army would respond to any similar attacks. U.S. soldiers commanded by Captain Bennett H. Hill (1815-1886) lodged at Fort Nisqually while Hill and Major Samuel Hathaway scouted for a fort location nearby. They selected the 640-acre farm that recently deceased English farmer Joseph Heath (d. 1849) had leased from PSAC, six miles north of Fort Nisqually on what was then called Steilacoom (now Chambers) Creek. The Army paid PSAC $50-a-month rent for the land Fort Steilacoom occupied.

Besides assisting in establishing Fort Steilacoom, Tolmie aided Indian Agent J. Quinn Thornton (1810-1888) in negotiating with the Snoqualmie Tribe to turn over members that U.S. authorities wanted to prosecute for murdering Wallace. On his advice, Thornton offered the tribe a reward of 80 blankets for six tribal members present at the attack, including two that witnesses identified as having shot Wallace. Snoqualmie chiefs turned the six over to Captain Hill at Fort Steilacoom and were paid with 80 HBC blankets purchased from Fort Nisqually. The Snoqualmies were tried at Fort Steilacoom in the first American court proceedings in what is now Washington. The two identified killers were convicted and hanged the next day, while the four others were acquitted by the American jury and freed.

Marriage and More Settlers

Tolmie continued dealing with American settlers claiming company land in disregard of the treaty provisions. In November 1849 Thomas Glasgow staked a claim right at Fort Nisqually, encompassing the Sequalitchew village and its burial ground, while Thomas M. Chambers (1795-1876) staked a claim at the mouth of Steilacoom Creek. Tolmie presented both settlers with written protests of the trespass, which they ignored, although the documentation later strengthened PSAC's claims in negotiations with the U.S. for compensation.

In early 1850 Tolmie traveled to Victoria, where Jane Work lived with her family. They married there on February 19 and she returned with him to Fort Nisqually. The marriage prompted Tolmie to abandon any plan to retire in Scotland and instead look forward after his service at Nisqually to settling with his family on Vancouver Island, where he purchased land as early as 1852. Their first six children were born while the family lived at Nisqually; six more after they moved to the island. Their youngest son, Simon Fraser Tolmie (1867-1937), became premier of British Columbia.

In April 1850 Englishman Edward Huggins (1832-1907) arrived at Nisqually, where he would live most of his life, becoming Tolmie's "righthand man" and eventual successor in charge of the fort, as well as an in-law – in 1857 Huggins married Jane Tolmie's younger sister Letitia Work.

The schooner Cadboro, which carried Huggins and a load of supplies from Fort Victoria to Nisqually, became the next point of contention between the company and American authorities. U.S. customs inspector Eben May Dorr seized the schooner and the goods it had unloaded for violation of new regulations – that the Company hadn't been informed of – requiring all British ships to undergo customs inspection before discharging passengers or cargo. Despite repeated protests by Tolmie and other HBC officers, U.S. officials held the ship and goods for two months, until head Customs Collector John Adair announced in June that HBC was innocent of smuggling and released them.

A major tipping point for both British and Native Americans in the Northwest came when Congress passed the Donation Land Claim Act in September 1850. It authorized settlers in Oregon Territory to claim title to up to 320 acres of land at no charge, sparking a surge in U.S. settlement. Most PSAC farms were soon surrounded by American settlers staking claims. Clerk Edward Huggins compiled a list of 70 such claimants from 1851 through 1853, all protested by the company as trespassers.

Caught in the Middle

The newcomers also encroached on tribal lands, increasing tensions between tribe members and settlers. To clear the way for American settlement, new territorial Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862) embarked on a program to get the tribes to cede nearly all their land to the U.S. and move onto small reservations. The way he did so sparked open warfare between some Indigenous people and settlers, leaving Tolmie and HBC caught in the middle.

Stevens began a rapid series of treaty councils in December 1854, meeting with members of south Puget Sound tribes at Medicine Creek in the Nisqually Delta a few miles west of Fort Nisqually. Stevens and his Indian agent Michael Simmons designated prominent tribal members as chiefs or subchiefs to sign the treaties. It was likely on Tolmie's recommendation that the Nisquallies designated were Leschi and Quiemuth. Although official documents claim no tribal members objected, the overall record, including accounts by tribe members who were present and others with contemporary knowledge, including Tolmie, make clear that at the council and repeatedly thereafter many leaders, notably Leschi, objected to the completely inadequate reservations assigned the Nisqually and Puyallup.

In the months that followed tension rose across the territory as Stevens imposed treaties on additional tribes. Fighting broke out east of the Cascades in September 1855 and spread to Puget Sound in October. The many tribal members who did not take up arms, including PSAC employees, suffered too. Most, under orders from Simmons, were interned. Native people working at Fort Nisqually were allowed to remain, but for their own safety they spent nights in the fort or locked barns. Even that protection was not always sufficient. In May 1856 a volunteer heading to a militia camp near Spanaway Lake east of Nisqually shot and killed Say-sillch, a well-liked employee known as Indian Bob, who was cutting firewood near a swamp behind the fort. (According to Huggins, writing in 1900, the location became known as Bob's Hollow, and a street in DuPont bears that name today.) Tolmie traveled to the camp with several Native witnesses, asking Colonel Benjamin Shaw to arrest the killer. Shaw did, but released him after armed militiamen surrounded and threatened Tolmie and his companions, who Shaw escorted to safety.

By then fighting had petered out. But the conflict prompted Stevens to provide substantially larger reservations for the Puyallup and Nisqually, presented to tribal leaders in August 1856 at a council where Tolmie served as interpreter. Ironically for Tolmie, who favored the larger reservations, some 3,300 acres of the new Nisqually reservation encompassed PSAC lands north of the Nisqually River. To preserve PSAC's right to compensation he had to file a protest.

Stevens wanted Leschi and Quiemuth prosecuted for killing territorial soldiers. Quiemuth was murdered before he could be tried. Leschi was tried twice. The first trial took place at Steilacoom, with Tolmie as one of two defense witnesses, and ended in mistrial when jurors did not agree. A retrial in Olympia resulted in a guilty verdict. Tolmie, many American settlers, and Army officers at Fort Steilacoom strongly disagreed with the proceedings and verdict. Tolmie wrote to Fayette McMullen (1810-1880), Stevens's successor, seeking a pardon for Leschi, and wrote an open letter to territory citizens demonstrating his friend's innocence. When Leschi was hanged in February 1858, Tolmie sent a wagon to Steilacoom to bring his remains home for burial.

Production at Fort Nisqually and its outstations, which slowed during the conflict, did not pick up afterward, as American settlers kept encroaching on PSAC land. Some also poached its cattle or helped themselves to field crops. Company officials focused on moving more operations to Vancouver Island.

Life in Victoria

Tolmie, promoted to Chief Factor in 1855, moved to Victoria in 1859 and took charge of PSAC farms on Vancouver Island. The Tolmies settled on the land he had purchased near Victoria. There, in addition to managing PSAC lands around the island, he developed his own Cloverdale Farm. In 1861 Tolmie was appointed to the Board of Management for HBC's Western Department. At the company's urging Tolmie sought election to the Vancouver Island legislature. After the island became part of the province of British Columbia, Tolmie served in the provincial legislature. He also served on boards of education for both island and province. He retired from HBC in 1871, but remained active in politics until 1878 and continued farming Cloverdale.

Tolmie had briefly resumed his personal journal during his 1841-1843 trip to Europe, but put it aside again until one last entry on an 1881 trip to Washington, noting "Here ... journalize again in this volume after a lapse of some thirty-nine years of life" (Journals, 383). Fittingly that final entry recounts visits to two other chroniclers of life in the early days of Washington Territory – Ezra Meeker (1830-1928), at whose home Tolmie wrote it, and James G. Swan (1818-1900). William Tolmie died at 74 on December 8, 1886.

Various plant and bird species, classified based on specimens Tolmie collected in the Northwest, are named for him. Tolmie Peak in Mount Rainier National Park commemorates his early exploration of the area (though it may not be the peak he climbed). In 1933 the National Park Service marked the centennial of Tolmie's exploration with a dedication ceremony, attended by British Columbia premier Simon Tolmie and other descendants, for a new park entrance on Mowich Lake Road featuring a plaque honoring Tolmie. Opened in 1975, Tolmie State Park in Thurston County a few miles northwest of the Nisqually Delta is named in his honor.