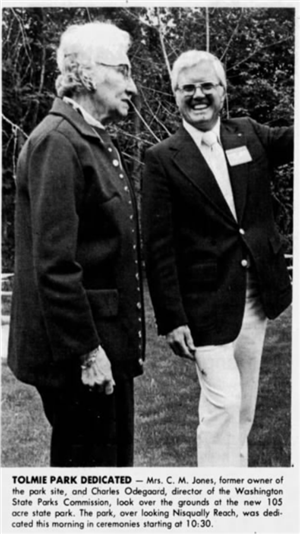

On June 20, 1975, dedication ceremonies are held for newly developed Tolmie State Park on the Nisqually Reach shoreline northeast of Olympia. The park is located on land long known as Jones Beach. Charles M. (1893-1969) and Ola M. (1897-1977) Jones moved there in the 1930s and operated a small resort on the sand-and-gravel spit that makes up much of the beachfront. They sold the property to the state parks commission in the early 1960s and it opened as Jones Beach State Park in 1965, but remained undeveloped for many years. In the early 1970s it was renamed in honor of Dr. William Tolmie (1812-1886), longtime head of the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Nisqually. Development of picnic shelters, restrooms, parking, and other facilities got underway in 1974. The work also included a beach-restoration project designed by engineer and environmental activist Wolf Bauer (1912-2016) using beach nourishment, a technique he devised that uses quantities of coarse gravel to protect an eroding beach, rather than artificial barriers like bulkheads or riprap, which Bauer found often contribute to rather than prevent erosion. The success of the Tolmie Park project will make it a model for beach-restoration efforts around Puget Sound.

State Park at Jones Beach

Tolmie State Park is located in Thurston County on the shoreline of southern Puget Sound a few miles northwest of the Nisqually Delta. Known for many years as Jones Beach for longtime owners Charles and Ola Jones, the property sits on a small cove just south of Sandy Point, where a sand-and-gravel spit protects an estuary formed by several small streams flowing into Puget Sound.

Ola Jones was a prominent local artist and founding member of the Olympia Art League who exhibited her work around Western Washington. Her "Brief History of Jones Beach," presented in The Olympian shortly after her death, recounts that her husband enjoyed fishing and often rented a boat to fish off Anderson Island, located just across Nisqually Reach from Jones Beach. "As he passed by this cove, he always wished he could own the property" (Contris). When the property came up for sale in 1936 the Joneses bought it. The steep road down the bluff made vehicular access challenging so they had cabins built in Tacoma and carried to the spit on the beach by barge. They lived and raised their two sons in a cabin on the spit and rented the others to boaters and fishing enthusiasts. Ola Jones recalled:

"[T]he cabins were rented to the same families year after year ... They all said those were the happiest days of their lives. There were get-togethers on the beach with picnics, swimming, golf practice, baseball and football when the tide was out on the sand flats. There was singing around the campfires at night" (Contris).

Jones also recalled that during World War II, Army troops from Fort Lewis used the area for amphibious tank-landing practice, with up to 40 tanks sometimes parked near their access road. Despite those disruptions and damage to their cabin by earthquakes in the late 1940s, the family lived at Jones Beach until the state bought the site.

By 1961, the state parks commission was negotiating with the Joneses to purchase their property as a saltwater park. The parties reached an agreement in 1962, and the state paid the purchase price in installments over the next three years. After parks commission director Charles H. Odegaard (1928-2007) made the final payment in 1965, Jones Beach opened to the public for picnicking and boating, with nearly 16,000 people visiting it that year.

However, despite several efforts over the years, it was not until the 1970s that the state was able to begin developing park facilities there. In June 1972 U.S. Representative Julia Butler Hansen (1907-1988) announced that the federal Bureau of Outdoor Recreation had made a $170,074 grant to build day-use facilities at the park, including restrooms, picnic shelters and other picnic areas, and parking, and construction got underway in early 1974. By then the park had been renamed in honor of Dr. William F. Tolmie. As head of the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Nisqually (which was located in present-day DuPont across the Nisqually Delta from the future park site) from 1843 to 1859, Tolmie not only played a significant role in the early non-Native settlement of the Puget Sound region but was also an accomplished naturalist who left detailed writings regarding the plants, animals, and natural features of the region.

The spit, a prominent part of Jones Beach, was slowly eroding when the state acquired the property. To preserve the spit and the important habitat of the estuary behind it, state officials initially planned to install riprap, a layer or wall of stone intended to control erosion. They were convinced to try a new approach after consulting Wolf Bauer, who was in the process of combining his longstanding interest in environmental protection and his profession as an engineer into a new career as a shoreline consultant.

Wolf Bauer

Bauer, then in his 60s, had already achieved prominence in several other areas. He was a well-known mountain climber and skier and helped found the Mountain Rescue Council. He also became an enthusiastic kayaker, helping introduce the sport in Washington and exploring most of the rivers of Western Washington and the shores of Puget Sound. Threats to the rivers he loved first inspired his environmental activism, as he got involved in the unsuccessful fight to prevent dam construction on the Cowlitz River and then the successful effort to preserve the Green River Gorge. He was also a professional engineer who spent most of his career designing manufacturing equipment and factories.

It was what Bauer saw with his engineer's eye as he kayaked Puget Sound shorelines that sparked his revolutionary work in shoreline design and protection. From his observations he concluded that solid artificial barriers like bulkheads and riprap, which had long been used to protect beaches and waterfront property from erosion, actually increased erosion damage along shorelines. It is the force of water withdrawing after a wave breaks that carries sediment with it, creating erosion, and those hard barriers had the effect of directing the full force of the withdrawing wave down onto the beach below them, increasing erosive force. In addition, Bauer noted that many of Puget Sound's high bluffs had frequent small slides and cave-ins, making them what he termed "feeder bluffs" supplying new sediment to down-drift beaches, especially points and spits, and bulkheading those bluffs reduced the material feeding the beaches. Bauer concluded that a far better way to control erosion and restore eroded beaches was to use porous gravel rather than hard rock structures. The porosity absorbed the force of waves so that they deposited sediment they carried on the beach and the return flow did not wash away beach material.

By the late 1960s, much of Bauer's environmental activism was focused on urging changes in how Washington's shorelines were managed and protected. He joined other conservationists in establishing the Washington Environmental Council, which advocated successfully for landmark environmental legislation including establishment of the Washington Department of Ecology in 1970 and passage of the Shoreline Management Act of 1971, which incorporated some of the shoreline policies Bauer advocated.

Bauer was also able to use his professional credentials to support his environmental advocacy by changing his consulting engineering practice to focus on shoreline resources, assisting both public and private landowners in restoring or redesigning failing shoreline systems and advising governmental agencies on regulation of new shoreline construction. It helped that he had gotten to know many environmental officials in the course of his earlier activism, including John Biggs, first head of the Department of Ecology. When Biggs invited Bauer to present his guidelines for shoreline protection to the new department, the staff initially found them, Bauer recalled, "too radical and new" (Bauer and Hyde, 230).

But he got a chance to demonstrate the effectiveness of his approach when the parks commission sought his assistance for some problems with the waterfront work getting underway at Tolmie. Bauer later wrote:

"When I learned that the eroding spit-beach at Tolmie State Park was to be 'saved' by riprapping in 1974, I convinced the Department of Ecology and the State Parks Commission of a great opportunity to fight the growing 'Riprap Syndrome' with the installation of a properly graded gravel-berm beach with a dune-grass backshore" (Bauer and Hyde, 237).

Pioneering Beach Restoration at Tolmie State Park

The existing conditions at the park when Bauer was called in provided a graphic illustration of his point that use of hard armoring like bulkheads actually contributed to beach erosion. The erosion of the spit, which parks officials sought to prevent, was due in part to bulkheads constructed along the bluffs "up-drift of the park [that] significantly impacted the already-limited sediment supply for the spit" (Johannessen, p. BN-28). In addition, a bulkhead on the beach at the base of the spit where a parking lot had been located blocked much of the sediment that would have accumulated along the spit.

Pursuant to Bauer's design, once the parking lot and its bulkhead were removed some 6,000 cubic yards of coarse gravel were brought in to stabilize and widen the spit. Most of the gravel was placed near where the parking lot had been, where some of it formed a large bulge in the shoreline at the base, or up-drift end, of the spit. This "overfill" provided a source of ongoing beach nourishment that would gradually wash down toward the point of the spit, so that it would not be necessary to bring in new sediment for many years. Additional gravel was placed along the waterward side of the spit, and a little bit along the "backshore" side along the estuary.

Bauer's beach-nourishment approach worked very well, as an evaluation conducted in 2012 in conjunction with development of state marine shoreline design guidelines found, noting it accomplished the goal of maintaining the spit for four decades. Long before that evaluation, the Tolmie State Park project had become a showcase and model for additional projects throughout Puget Sound. Bauer himself designed more than 30 additional beach-restoration projects around the Sound, including a dozen at City of Seattle parks and beaches such as Alki Beach and Carkeek, Myrtle Edwards, and Discovery parks. Many other designers also utilized his principles to design similar projects, which were often referred to as "Bauer Beaches."

When the state's Marine Shoreline Design Guidelines were published in 2014, Bauer's beach-nourishment approach was one of the primary recommended techniques for shore protection, and the publication noted his role in introducing it: "In the Puget Sound region, gravel beach nourishment was pioneered by Wolf Bauer ... Early Bauer nourishment projects have served as models for landowners and designers since his first public project in Puget Sound" at Tolmie State Park (Johannessen, p. 7.1.1). Bauer was one of two shoreline experts to whom the guidelines publication was dedicated:

"This document is also dedicated to Wolf Bauer, now 101 years old, who basically invented the field of soft shore protection in Puget Sound and Lower British Columbia. Wolf worked as a tireless proponent of understanding Puget Sound region coastal processes and working for conservation and restoration of beach and marshes, along with scores of beach creation and enhancement projects. Wolf heartily applied his hard earned knowledge gained from spending thousands of hours walking and kayaking our shores" (Johannessen, p. ii).

Dedication Ceremonies

By June 1975, beach restoration and park construction had been completed. There were two day-use areas, one on the bluff above the beach and one near the estuary at the beach level, each with a picnic shelter, restrooms, additional picnic areas, and parking. (The park was and in 2025 remains day-use only, closing overnight with no camping allowed). There were also hiking trails, swimming access, fishing and clamming areas, and an underwater park for divers, created by sinking three barges off-shore to create marine-life habitat.

The Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission dedicated Tolmie State Park in ceremonies held on Friday, June 20, 1975. Commission director Charles Odegaard served as master of ceremonies for the event, which featured a keynote address by State Senator Harry B. Lewis and commission chairman Thomas C. Garrett officially presenting the new facilities to the public. Ola Jones gave a history of the Jones Beach property as part of the ceremonies and the Olympia Art League sponsored a potluck picnic immediately following the dedication.