City Light, Seattle's publicly owned electric utility, began to take shape in 1902, when voters approved bonds for a hydroelectric dam on the Cedar River. The project, completed in 1905, was a direct response to the virtual monopoly held by Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power Company (known as Puget Power) over local electrical service and street railways. City Light became an independent city department in 1910 and competed head to head with Puget Power for the next 40 years in an often bitter political and economic struggle for control of regional power markets and supplies.

Let There Be Light!

An electric incandescent light bulb flickered to life for the first time in Seattle (and west of the Rocky Mountains) on March 22, 1886. Current was supplied by a steam-powered generator installed by Sidney Mitchell and F. H. Sparling, agents of Thomas Edison. They later formed the Seattle Electric Light Company with local investors and won the first municipal franchise to provide electricity for lighting public streets.

In 1887, engineer Frank J. Sprague demonstrated a new use for electricity: powering streetcars and trains. "Electric traction" soon became the dominant market for fledgling electric utilities across the nation. Just two years after Sprague's prototype electric streetcar debuted in Richmond, Virginia, Seattle entrepreneurs Frank Osgood (1852-1934), E. C. Kilbourne, L. H. Griffith, and Franz Theodore Blunck (1841-1918) financed an electric streetcar line on Front Street, now 1st Avenue.

Electric Traction

Despite public skepticism and fears of runaway lightening bolts, the first car performed flawlessly on March 30, 1889. Ms. Addie Browns, an investor in the Seattle Electric Railway and Power Company, had the honor of being the line's first passenger.

The new electric streetcars continued running through the Great Fire on June 6, 1889, and private street railways quickly spread across the growing city as it rebuilt. In 1900, most of these systems were purchased and consolidated by the new Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power Company. Although represented locally by banker Jacob Furth (1840-1914), Puget Sound Traction was actually controlled by the national utility cartel, Stone & Webster.

Political Friction

Monopoly ownership of the city's primary electric utility and public transit motivated local reformers to push for a publicly owned alternative, which had been debated as early 1890. Public ownership advocates led by City Engineers George Fletcher Cotterill (1865-1958) and Reginald H. Thomson (1856-1949) prevailed in convincing officials and voters to develop an electric power plant at Cedar Falls in the city's newly acquired Cedar River Watershed. (The region's first hydroelectric facility was completed at Snoqualmie Falls in 1898 and continues to generate power under management of Washington Energy.)

Private utilities led by Puget Power bitterly resisted the Cedar River project and other local forays into municipal ownership. Voters were not persuaded and approved $500,000 in bonds for the new power plant on March 4, 1902. They also approved several additional bond issues to expand the plant and Seattle's city-owned electrical system.

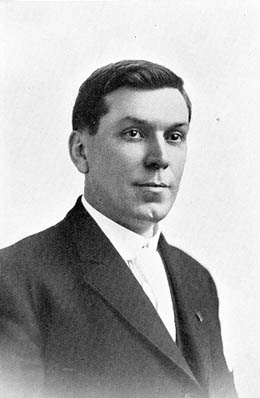

Enter J. D. Ross

Future City Light Superintendent James D. Ross (1872-1939) supervised the Cedar Falls project, which transmitted its first power to a Seattle substation on January 10, 1905. The Seattle Water Department took possession of the private Seattle Electric Company's street lighting system on May 1, 1905. Voters approved an additional $600,000 in bonds to expand the system on March 6, 1906, but the plan was delayed by lawsuits filed by private utility interests.

Voters approved $800,000 more in bonds on December 29, 1908. The Seattle City Council created an independent Department of Lighting on April 1, 1910, which prepared a $1.4 million expansion plan and submitted it to resounding voter approval on November 8, 1910.

L. B. Youngs served as the first Superintendent of Light and Water that same year, and was briefly succeeded by R. M. Arms as Superintendent of Lighting. J. D. Ross took charge as the new Superintendent of Lighting in early 1911. Except for his brief dismissal in 1931 by Mayor Frank Edwards (who was promptly recalled), Ross guided City Light until 1935, when President Franklin Roosevelt appointed him to the new Securities Exchange Commission. Ross died four years later. His legacy is epitomized by City Light's three dams on the Skagit River, for which he obtained federal licenses in 1918. The Skagit complex remained Seattle's largest single power source until City Light brought its Boundary Dam online in 1967.

From Bad Bargain to New Deal

Also in 1918, the city purchased most of Puget Power's Seattle electric streetcar lines (the private firm retained ownership of its electric interurban lines to Tacoma and Everett). The controversial transaction was seriously overvalued and saddled the city street railways with crushing debts. A grand jury found Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson (1874-1940) guilty of stupidity but not of conspiracy.

Private utilities also attempted to make public ownership of electrical systems illegal in 1930, but they were defeated in a state-wide vote. Federal New Deal anti-trust regulations dissolved the Stone & Webster utility cartel in 1934 and Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power (antecedent of Washington Energy) was reorganized under local ownership.

The private utility repeatedly offered to rescue Seattle's streetcar system -- in exchange for City Light -- but Seattle declined and shifted to buses and "trackless trolleys" beginning in 1940. City Light and Puget Power competed fiercely until November 7, 1950, when a scant majority of 754 voters approved municipal acquisition of remaining private power assets and services within the city limits. Since then, City Light has been Seattle's exclusive electric power provider, while Puget Power focused on the suburbs. The latter was reorganized in the 1990s through a merger with Washington Natural Gas to create today's Washington Energy and Puget Sound Energy private utilities.