In the spring of 1930, Filipino farmworkers on Vashon Island and in South King County are targets of hateful and biased treatment by white farmworkers, some of whom are fearful of losing job opportunities in the first year of the Great Depression. Filipino workers who already are paid roughly half of the white workers’ salaries are harassed, dynamite is exploded outside their living quarters, their jobs are limited to those unwanted by others, and white farm owners who hire Filipino workers are targeted with death threats. None of the people harassing Filipino workers will be arrested, though one of the Filipino workers who insisted a brawl was in self-defense will be charged with felony assault.

Brawl on Vashon

Farms on Vashon Island and in South King County were growing in the late 1920s, and that brought demand for additional labor. In April 1930, the Vashon Island News-Record reported that roughly 50 Filipino workers were expected to arrive in May to work the fruit ranges around the Burton area of Vashon Island as soon as the fruit was ready to gather. Several ranchers wanted the additional workers, worried that a lack of labor would mean a loss for land owners. That year, census data recorded 3,480 Filipinos living in Washington, up from 17 Filipino resident two decades earlier.

The night of Monday, May 12, 1930, Filipino farmworker Louis Modaranga was in a brawl with four white men. Modaranga, who was employed at the Steen Mill box factory in the Ellisport neighborhood of Vashon Island, later testified that several white men appeared suddenly before him and his fellow worker and began fighting. Modaranga admitted he might have struck one with a carpenter’s tool, but testified neither he nor his fellow Filipino worker carried knives. A King County deputy sheriff, F. J. Shattuck (1891-1949), testified be believed the assault was provoked. The incident was first publicly reported four days later in the News-Record. The newspaper account said four young men – Ira Hastings, Donald and Charles Hayes, and Cecil Petrie – went to a cottage occupied by several Filipino workers, including Modaranga, "presumably hunting for employment" ("Arrest Is Made …"). The night after the incident, dynamite was exploded outside a cottage occupied by Filipino workers in Ellisport and at another cottage occupied by Filipino workers in the Shawnee area, blowing in a window and door.

The story was picked up by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, which described "race riots" including the stabbing of a white man by Modaranga and the bombings at Filipino cottages. The P-I reported one of the dynamite charges didn’t explode, and King County Sheriff Claude G. Bannick (1876-1957) told the newspaper no additional deputies would be sent unless further trouble developed. The afternoon of May 16, The Seattle Times described a "Filipino war" that kept a Sheriff’s Office skeleton crew at the ready for riot calls with help from the highway patrol.

Hastings, a 20-year-old house painter, according to census records, was the young man who reported the stabbing. He and the others claimed the Filipinos started trouble without provocation. That led to Modaranga’s arrest; his bail was set at $1,000. News accounts didn’t question why the four young men went to Modaranga's home.

In a June 5 hearing, a justice of the peace bound Modaranga to King County Superior Court on a second-degree assault charge for the alleged stabbing of Hastings. But what happened next appears to be lost to history. In October 2024, after more than a month of searching, Superior Court Department of Judicial Administration staff said they found no record of Louis Modaranga in a search of criminal records from 1923-1937. The last mention of him in local papers was in June 1930, when a deputy prosecutor said he expected Modaranga to be released and expected the courts to assess trial costs against the white plaintiffs. In another newspaper account, the King County prosecutor said Modaranga was unjustly held.

Genealogy records have sparse information on those involved. There’s no Louis Modaranga in census records, though a Pedro Modaranga – possibly his legal name – was a 29-year-old Vashon fruit-farm laborer born in the Philippines. Pedro, also referenced as Pete in census records, worked as a cannery and fruit-farm worker and died on Bainbridge Island in 1977. He never married.

Auburn Workers Terrorized

Anti-Filipino racism wasn’t limited to Vashon Island. At a May 8, 1930, meeting of Kent vegetable growers, packers, and merchants, the group of at least 25 agreed to not employ Filipinos in jobs where they believed white labor could be secured in the midst of the Great Depression. There was pushback from growers who said field work had "some tasks that no American or Japanese workers will undertake, and to carry on the lettuce industry Filipinos must be employed or the industry will suffer" ("Anti-Filipino Feeling ..."). The agreement was to not employ Filipino workers in shed work or packing plants "and where they are employed in the fields, efforts will be made to educate them to keep their place" ("Anti-Filipino Feeling …").

Two days earlier, a self-appointed group of vigilantes terrorized Filipino workers at farms in Kent and Auburn where they were employed. The Auburn Globe-Republican described the incidents in a front-page story:

"In most cases the Filipinos were aroused, chased from their bunks and admonished to leave the country. One report made at police headquarters here yesterday stated that money and property had been stolen, but officers at Kent later scouted the story.

"Trouble had been brewing for some time about the vegetable gardens between Auburn and Kent and north of the latter town. It is said that numbers of white laborers were thrown out of work when some 200 Filipinos were imported to do work of about half white wages. Wage scale is said to have been cut from around 50 cents an hour to 20 and 25 cents" ("Anti-Filipino Feeling …").

The article said a first call came from a farm about a mile south of Kent owned by John Mullen, and that calls "came thick and fast" afterward. A police captain claimed many were "fictious alarms" to Kent headquarters, "keeping his men busy on wild goose chases all night" ("Anti-Filipino Feeling …").

According to the Globe-Republican, three Filipinos – Thomas D. Layos, Octavio Parida, and Marcelo Buers – were aroused shortly after midnight, badly beaten, and had property and $110 stolen (roughly $2,078 in 2025 dollars, adjusted for inflation). Police told them if they returned to their residence, which Layos had leased, they would find the missing property and money. But there was no follow-up report in the Auburn paper, the story wasn’t picked up by The Seattle Times or Post-Intelligencer, and there’s no indication that a suspect was ever arrested – or that the money and property were retuned.

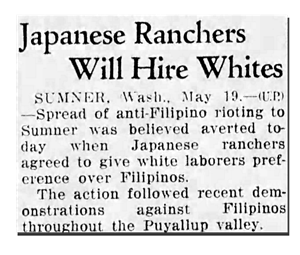

A week after that report, the Post-Intelligencer ran a story about Port of Tacoma Commissioner Charles W. Orton (1877-1963) getting threats of death and property destruction as part of the so-called race riots. Orton owned a bulb farm in Sumner, roughly eight miles south of Auburn, and received an anonymous letter with skull and crossbones saying he’d be killed if he didn’t discharge his Filipino workers. His brother, Ed Orton (1881-1975), who also had a farm near Sumner, received a similar death threat. The State Patrol watched their ranches, though a suspect was never identified. Charles Orton grew his bulb farm into one of the state’s largest, served as president of the Washington State College Board of Regents in 1936-1937, and lived to be 86. His brother, Ed, lived to be 93.

Resentment from Union Organizers

Lettuce production in south King County increased dramatically in the 1920s. In 1929, growers in Kent alone shipped 800 railcars of lettuce and expected to exceed that in 1930. Auburn shipped 265 cars in 1929, with about an acre and a half needed to fill a single shipment. Japanese American growers in 1930 wanted a second crop for their lettuce land, and suggested cabbage and cucumbers were possible. Rapid growth of the pea, cauliflower, and rhubarb land also led to talk of a cannery in Auburn – itself a growing town. Auburn’s 1930 population was 3,927 – 24 percent higher than the census figure of 10 years prior – and the trade territory of 24 nearby communities (including Black Diamond, Muckleshoot, Ravensdale, and Pacific) reached 15,077 people. Separately, the city of Kent had 2,305 people in 1930, Enumclaw counted 2,078, and Renton was the largest King County city outside Seattle with 4,057 residents.

Responding to the farm-labor issue and questions of Filipino workers, the Auburn Japanese Association calling a meeting at the Auburn Chamber of Commerce the night of May 10 and the crowd of roughly 35 including representatives from organizations in Sumner, Algona, Pacific, Kent, and Auburn. H. K. Fukuhara, a Japanese merchant, and W. A. McLean, cashier of the Auburn National Bank, presided. George Bowles (1875-1930), President of the Kent Commercial Club, explained the labor agreement limiting Filipinos to jobs that he believed could not be done by white or Japanese labor, and added that Filipino workers were also not to be employed in the pea fields. They were hired, he said, because additional farmed acreage required the additional laborers.

Auburn Mayor J. W. McKee – echoing sentiments of others who spoke – said he hoped every opportunity would be given for white labor to handle the work, and ensured that whites would take the jobs. "He said the union organizations resented the fact of the invasion of the Filipinos, and thought the Japanese would be acting wisely if they let it be known they would hire white labor" ("Conference Is Held …"). Fueling the hatred was discussion that some Filipino workers were being paid 35 to 40 cents – nearly the price white workers were paid for the same job. The meeting ended with the promise of a committee from the Japanese Association and Auburn Chamber of Commerce appointed to establish a register for those who wanted field work.

While the most public anti-Filipino acts happened locally in 1930, biased behavior continued for years, including national attempts to limit immigration. The 1935 Filipino Repatriation Act pressured Filipinos to return to the Philippines with free passage, and more than a third of Washington’s Filipino population had left the state before the act was declared unconstitutional in 1940. Six years later, President Harry S. Truman – who had granted U.S. citizenship to enlistees in 1942 – signed the Filipino Naturalization Bill, enabling Filipinos to become citizens.