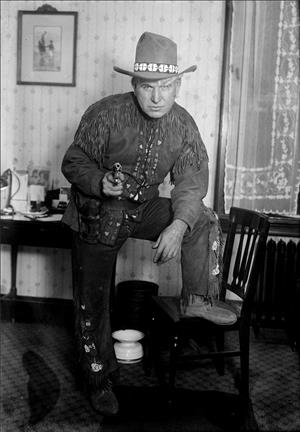

Joseph Knowles (1869–1942) was an American artist and adventurer best known for a 1913 survival stunt in the Maine wilderness, where he claimed to have lived unaided for two months. Following that episode, Knowles sought to capitalize on his fame by venturing into various fields, including a brief and unsuccessful foray in the film industry. In 1917, he relocated to the Long Beach Peninsula in Washington and settled in Seaview. There, he reinvented himself as an illustrator, producing popular drawings and paintings that depicted scenes of the American West, including Native Americans, shipwrecks, and wildlife. His artwork garnered attention, leading to commissions such as 46 oil paintings for the Monticello Hotel in Longview. Despite his public persona, personal accounts suggest that Knowles had a complex relationship with his community, sometimes expressing disdain for his neighbors. He continued to reside in Seaview until his death in 1942 at the age of 73. His legacy persists, with some of his sketches and memorabilia displayed at the Long Beach Peninsula Trading Post serving as a testament to his multifaceted life and career.

"Nature Man"

On the Long Beach Peninsula north of Ilwaco, a self-styled "nature man" spent the last decades of his eventful life. His celebrity lay in the past, the profits from his golden years long squandered. Using shipwreck timbers and flotsam, he hammered together a house so near the Pacific that a wave-tossed log once drove through his front door. Much like Johnny Schnarr (1894-1993), the fabled Northwest rumrunner, Knowles's native smarts outran his formal education, and both men were adept with their hands. While Schnarr cleverly evaded detection during Prohibition, Knowles incited all the publicity he could. In 1913, after a two-month sojourn on the Maine frontier – a sojourn that he claimed he had undertaken solo – he was celebrated by 20,000 cheering fans in Boston.

His life story, laden with controversy, has intrigued historians for more than a century. How could his wilderness sojourn have spawned so many newspaper headlines, speaking gigs, engagements on vaudeville stages, and at least two silent films? How did a man in animal skins manage to cultivate such a gullible public? Knowles’s allure stemmed from a "legacy of frontier fakery," or so the subtitle of his biography insists (Motavalli). His fame must also credit newspapers that were competing keenly for readers. Indeed, his story in great measure is equally a story of journalistic fakery. Exploiting a kindred species today, TV shows featuring unclad actors in outdoor environs are much in vogue. Like those so-called reality game shows, Knowles shed his clothes to conduct a stunt in survivalism that his promoters situated as scientific. His celebrated career ended, as it had begun, with his making public art by contract and commission.

In the American Grain

A boyhood filled with hardship lay the foundation for Knowles. The Gilded Age in American history refers to a period roughly from the 1870s to 1900 – the term "gilded" denoting a thin layer of gold that made business dealings appear prosperous on the outside, but which camouflaged lies and corruption within. A return to nature was widely held to be a cure for such a contagion from capitalism. Knowles had grown up hunting and trapping by necessity for sustenance in Maine because his family was so poor.

Joseph Greenleaf Knowles (1833-1915), his father, had been crippled in the Civil War and could not provide for his family in Wilton, Maine. He had to rely on his wife, Mary Wilcox Knowles (d. 1923), as the "sole source of support for ten years" (Motavalli, 29). Mary hauled wood, picked berries, took in piecework, made moccasins, and wove baskets. The four children ate a lot of sowbelly and cornbread. When he was old enough to tote a gun, Joe Jr. began to bring home wild game to sustain the family. At about the same time, he acquired a precious set of crayons and began to sketch. His self-taught visual art would become a lifelong enterprise.

An early self-portrait shows the flair he used to construct the self-legend and lore that would inform his later exploits. The untitled oil portrait shows him slogging through deep snow with a rifle in one hand and a massive moose head with full rack on his shoulder (Motavalli, 35). Likely drawing from his days as a hunting guide, the portrait requires viewers willingly to suspend their disbelief, for most mortals would not have the capacity to haul a horned moose head of 40 to 60 pounds in deep snow. But Knowles presented himself as no mere mortal. He claimed he ran away from home after a parental scolding and became a sailor at 13. From Portland, Maine, to Pensacola, Florida, to Cuba and back north to New Brunswick, he got his sea legs. He became a Navy man at 19, but, "We may have to take Knowles's word for that Navy enlistment" (Motavalli, 37). Research on his service record turned up nothing. He said he served in the Merchant Marine as well in "Europe, Africa, Asia, the West Indies, and South and Central America" (Motavalli, 37). He also claimed he traversed the Great Lakes and lived among the Sioux and Chippewa Indians, whom he credited with much of what he learned about wilderness survival.

An Artistic Life

Having played with crayons and given his sketches to friends, Knowles yearned to make an actual living with his skill. When a magazine bought one of his paintings to use as cover art, it inspired him to rent a Boston attic for use as a makeshift studio. He spent 10 years practicing his craft and peddling his creations to magazines and newspapers. Thanks to exposure to outdoor life as a boy and a young man, nature was his nonstop topic. He burned and painted leather for camps and dens, and drew fish and animals for sportsmen groups. He took one art class and claimed the teacher kicked him out, fearing that he was good enough to seize the teaching job himself.

He continued to sketch in the first decade of the twentietch century and sell art to periodicals, including Field and Stream, National Sportsman, and Baseball. He also drew for glossy fashion magazines – as counterintuitive as that might seem for one who was soon to be lauded as the robust nature man. But the fashion art of his first wife, the former Sadie Andrews, whom he married in 1893, explains his foray into that line of work. In interviews or writings, he does not discuss his wives or paramours. By 1910 the two had divorced, and she made shift by living with her sister and working as a hotel chambermaid. Knowles’s first steady job as an artist was for the Boston Post from 1907 to 1910, during which he rented a studio in Bradford, Vermont.

The brainwave that ignited his avatar as a naked man in the woods developed in tandem with associates at the Post. Drinking in a Boston bar, by one account, Knowles boasted to those associates that he could thrive alone in the woods without clothing for two months. A light came on for them, and the promotion stunt was born. The first story about Tarzan, Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950), had appeared in the pulp magazine All-Story in October 1912, one year before Knowles set out, and then as a book in 1914. The noble-born Tarzan swung from jungle vines, befriended wild animals, and dressed himself in a loincloth. A white and flabby Knowles wore a jockstrap and bared his behind for publicity photos. The Boston Post folks might have reasoned that if his outdoor experiment killed him, the paper would still have gotten lots of good copy and be poised to publicize his vain ambition and document his ordeal.

Stagecraft is an art, like any other. Nature was to be Knowles's stage. The newspaper agreed to stage-manage him and subsidize his timely escapade. He proved to be the ideal actor for the role.

Summoned by the Wild

Besides the model of the ape-man Tarzan, writer Jack London (1876-1916) contributed to the zeitgeist for Knowles’s experiment – zeitgeist being German for "spirit of the time" or "spirit of the age." London’s The Call of the Wild was published in 1903, and his White Fang followed in 1906. Both novels explore themes of survival and the empathies between humans and animals in the harsh environment of the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush (1896-99). Rumor had it that Knowles and London drank together and were cooking up some stunt, but London died too soon. London’s novels have canine protagonists, Buck and White Fang, whose transformations mirror Joe Knowles’s themes of nature versus nurture, survival, and the wild’s influence on character. The dogs’ trajectories cross. Buck goes from domestic to wild, while White Fang evolves from wild to domesticated. Such transitions were top of mind in the United States at that time, when many families were gravitating from ranches and farms to urban factory jobs.

Knowles, with the Boston Post promoting his boasts and underwriting his venture, vowed to spend two months in the wilds of Maine. He would enter without clothing or tools of any kind. Everything he needed he promised to craft from materials found in the woods. Food was to be gathered or hunted; fire, conjured by the friction method. Communication with the outside world would be undertaken on missives written with charcoal from his fire pit. Sketches and letters, done on birch bark, would be left covertly at a place that had been prearranged. Knowles pledged to have no contact with other human beings during those eight weeks.

The outset of his experiment was attended in the Maine woods by a small army of reporters and well-wishers. He smoked a final cigarette on August 4, 1913, and set off in the rain. Some of the commentators called his jockstrap a G-string, accenting the voyeuristic element that would chronicle his unclothed competition against wild animals for his safety and his food. The promise of vicarious thrills attracted readers to the newspaper accounts. The editors and publishers of those accounts were excited to draw new ad copy and subscribers. Fame and fortune motivated Knowles to get modestly naked before the gaze of an appreciative America.

A counterpart to Joe Knowles is survivalist Bear Grylls (b. 1974). While filming his show Man vs. Wild (known as Born Survivor in the United Kingdom), a scandal emerged in 2007. Known for extreme survival stunts, Grylls was accused of misleading viewers by not always sleeping in the wild as portrayed on TV. Reports revealed that during the filming of some episodes, he slept in hotels or lodges rather than in the harsh conditions he showcased. One example included an episode filmed in California’s Sierra Nevada, where he appeared to build a natural shelter but was later reported to have crashed in a luxury lodge. The Discovery Channel and the show’s producers admitted that certain scenes were staged or reenacted to enhance educational value.

The Survivor television franchise has been adapted in more than 25 countries since its inception in the late 1990s. As of January 2024, the American version alone has aired 45 seasons since its debut in 2000, with the 46th season premiering in February 2024. Beyond the Survivor franchise, the survival reality TV genre has expanded significantly to encompass many shows that challenge participants to endure harsh conditions. Indeed, Washington has its own celebrity participant. "Former Survivor contestant Nick Brown has become the first Black person to be elected attorney general in Washington state" (Adams). While he was a student at Harvard Law School in 2001, Brown was a cast member on Survivor: The Australian Outback.

Knowles got snared like Grylls did, though his critics took some time to gather the most damning evidence against him. Before he set out, he pledged to dress himself in animal skins, requiring him to skirt game laws in Maine, where hunting seasons in summer and early fall when he set out were closed. Joe strangely claimed he wrestled a deer and broke its neck with a twist before skinning it to make himself leggings. More damning was his claim to have trapped a bear in a pit only 4 feet deep. That bear skin became a coat, which was later reported to have hidden bullet holes. Worse, a report that was 25 years unfolding revealed he probably slept in a new-built cabin and enjoyed a woman’s company. The witness reported seeing tin cans and beer bottles, a modern man’s midden, in a pile hidden behind the covert cabin (Motavalli, 81).

Had Joe’s fans heard the whispers or read the allegations, they might not have cared. And so, Joe emerged from his eight-week sojourn in the New England wilderness a hero. The only wrinkle was his violation of game laws. To shield him from that breach, handlers hired an Indian guide and had him emerge in Megantic, Quebec. The troupe of supporters and reporters there included Maine game wardens, who levied a small fine before accompanying him back to the banquets and cheering crowds awaiting him in Massachusetts and Maine. He spruced up in a dress suit at first, but popular demand soon had him clad back in his stinky skins.

After he became the talk of the nation, his handlers launched him on a tour with the Indian Ishi (c. 1860–1916), the last known member of the Yahi, a group of the Yana people indigenous to Northern California. Ishi is often referred to as "the last wild Indian" because he lived most of his life outside of Euro-American society. The two men competed on vaudeville stages to see which one could start a friction fire fastest or shoot an arrow with most accuracy. Knowles earned $1,200 a week for 20 weeks with the B. F. Keith Vaudeville Circuit (Holbrook, 152). Adjusted for inflation, that sum totals more than $573,000 in 2025 dollars.

The Boston Post had accomplished its goal. The only quibbles arose from competing newspapers, particularly the Boston American owned by William Randolph Hearst. The Boston marketplace, saturated with 10 to 15 daily newspapers, made for fierce rivalries. Lawsuits and countersuits were filed about his story, but Knowles's notoriety proved golden. In fact, a year later Hearst lured Knowles out to California to reprise his feat in the Siskiyou Mountains. There, home to Hearst’s media empire, his flagship San Francisco Examiner would publicize that second cunning stunt. Professors and scientists this time were to observe him outdoors in 1914 and vouch for the authenticity of his scientific experiment in survival.

But that second excursion went bust. Hunters and miners had driven away the game animals Joe needed. Gawkers kept seeking him out to inquire about his progress. Within six days, too, the start of World War I knocked his naked escapade off the headlines. Demoted to the back pages of the Examiner, he got less publicity than he had hoped for and too little gratification as the "nature man." But he had discovered Washington and the American West, where California led the nation in film production, and every shred of evidence says that he made plans to stay.

Celebrity Author

Four weeks into the hubbub that accompanied his return in Maine, fans learned they would soon have a chance to read his forthcoming book. Alone in the Wilderness, One Man’s Survival in the Forests and Nature of Maine as a Wild Man of America came out in early December 1913, rushed into print and ghost-written. His biographer speculates that Michael McKeogh of the Boston Post wrote it. Knowles could have had no time between his nonstop public appearances to put pen to paper following his emergence four weeks before. The book includes a range of undocumented borrowings from English poetry; it quotes Oliver Goldsmith and William Wordsworth without identifying them; it lifts from the Bible. While the rush of publicity was keeping him busy, Knowles was also somehow managing to make his first film.

The scattershot structure makes the book tough to track. The first half shares tales of encounters with wild animals, but the second half meanders into recollections from earlier times in his life. It loses focus on the great Maine escapade. Interspersed for scholarly sincerity are philosophical reflections that may be summed up in a single sentence: "I wanted to get away from the sham side of modern life, and from people" (Alone ..., 34). Contradicting that claim, he laments how morbidly lonely he got and how he almost threw in the towel before the two months were up. One chapter, titled "Wilderness Neighbors," suggests that his ghostwriter knew Henry David Thoreau’s Walden and its chapter "Brute Neighbors." The cover image for Joe’s book, a retouched photo of him clad in skins, makes him look like John the Baptist. If that biblical figure fed on locusts and honey, Joe fed chiefly on fish and berries he gathered.

His book ends by pitching future proposals for projects he hoped to get off the ground. He sings the praises of the Boy Scouts, at one point directly addressing them, as if speaking from the pulpit: "Boys, you all have brains" (Alone ..., 90). Robert Baden-Powell (1857-1941), a British Army officer, founded the Boy Scouts in 1908. In the U.S., inspired by the British scouting movement, the Boy Scouts of America was founded in 1910 by William D. Boyce (1958-1929). Knowles might have hoped to succeed Boyce as leader of that organization. In one tangible result of his affiliation with them, Knowles directed a Scouts summer camp near Ilwaco in 1917. Much later, in 1939, the American Scouts issued a fresh edition of Alone in the Wilderness. The last quarter-century of his 73-year life, Joe Knowles spent on the coast of Washington state.

In the final chapters of Alone, he fertilizes a project that would never sprout. His College of Nature, if he could create it, "would result in a marked change in child literature. Through the books that would be written the child would come to love the woods rather than to fear them" (Alone ..., 108). The growth of cities and industry made for a widespread sentiment that humankind was degenerating due to artificiality and confinement. Living outdoors, Knowles held, might freshen stunted frontier roots. Long and happy lives might ensue from a month spent in wild areas every year. Historian Roderick Nash sees such outings as "partly masochistic," meant to prove that "man still deserved his place atop the Darwinian tree of life" (Nash, 328). Alone in the Wilderness is reputed to have sold 300,000 copies, all of them now difficult to find. Were those copies read to pieces – or were sales figures exaggerated, like other inflated claims?

Among Knowles’s many uncollected writings, he penned a script for a silent film that was never made. A Modern Robinson Cruso [sic] is set in Mexico. After a shipwreck, Knowles-as-hero lands on a desert island. He befriends critters displaced conspicuously from their native environs (invalidating his claim he had traveled in Central America as a young man). In the abortive script, monkeys toss coconuts from trees. A deer plunges out of a thicket. A wild coyote is encountered. The hero fights an alligator before he builds a boat and, "with monkeys as his passengers sails back to the mainland, where his old friend the governor is waiting with outstretched arms. The End" (Motavalli, 171). Chronicling Knowles’s various inspirations with a straight face can be difficult, in part because aesthetic standards were so different in his day.

The celebrity author got paid to make two silent films. Due to industry neglect and the poor quality of the celluloid, neither has survived. Nitrate stock was the standard medium for motion pictures from the late-nineteenth century until the early 1950s. While the material made from cellulose nitrate offered high-quality images for its time, it was flammable and prone to deterioration. Cellulose acetate was introduced in the 1920s and 1930s as a safer alternative, but Knowles by then had widened into late middle age and tumbled out of public view. His two outdoor adventure films were titled The Nature Man (1913) and Alone in the Wilderness (1915).

Second Marriage, Third Excursion

On November 13, 1914, in Tacoma, Knowles married Marion Louise Humphrey (1886-1947). The two met when they were illustrating for the Boston Post in 1907. Records are so sketchy that no one knows exactly when they coupled, but one may speculate that they toured the nation under cover of journalistic darkness due to the scandal their unmarried cohabitation might have caused. Female admirers or former lovers mailed Knowles torrid letters and offered to make a life with him, but Marion stuck beside him till he died almost three decades later. In semiretirement in Seaview on the Long Beach Peninsula, she hand-rolled cigarettes the two of them shared, while abetting his fondness for homebrew and white lightning (Motavalli, 217).

Knowles, at 45 years of age when they married, was at the peak of his celebrity. If his outing in the California mountains had fizzled, as measured by an absence of PR, other aspirations were occupying his mind and time. He was delivering lectures in the Golden State and had a second film to make. He toured the Orpheum Circuit, which was the largest and most prestigious chain of vaudeville theaters in the U.S., known for showcasing a variety of live entertainment acts, including comedians, singers, dancers, magicians, and acrobats. He wrote or proposed screenplays he would pester filmmakers with. He had another project that required him to be naked outdoors, which was to pair him in 1916 with the young film actor Elaine Hammerstein.

She was first cousin to the lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, who would write some of the greatest lyrics in musical theater history. Elaine and Joe were to live outdoors and demonstrate subsistence skills. In the prepublicity that boosted the project, they were positioned theatrically as Dawn Man and Dawn Woman. Those names suggested that they were to be identified as cave people, Adam and Eve, or both. An unclothed couple romping, as if in the Garden of Eden, would guarantee a certain titillation. Hammerstein was only 20, less than half Knowles's age. After she grew convinced that the project would advance her film career, she agreed to its terms.

It was to take place in the Adirondacks of upstate New York at a town named Old Forge. In the planning stages, the quackery was covered in depth by the New York Journal American, a newspaper owned by William Randolph Hearst. He had handpicked Hammerstein to star. The Journal American, like the San Francisco Examiner and Hearst’s other papers, aimed to captivate readers with sensational tales. In large bold type one headline screamed, KNOWLES HURLS DEFY AT GRIM NATURE (Holbrook, 154). Hearst was also investing in silent films and newsreels. Those media were distinct from one another in that newsreels were nonfiction and shorter, only 5 to 10 minutes long, while films were fiction and 60 to 90 minutes long. Joe likely hoped the Adirondacks romp had the potential to become a film. Rehearsing as Adam to Hammerstein’s Eve, whom everyone knew was soon to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, Joe labored to teach her how to build a hut, harvest frog legs, and cross a beaver dam without a dunking (she failed). Other outdoor tasks likewise seemed a bad match for her background.

The project began on September 23, way too late in the year for that northerly locale. Hammerstein’s grass skirt offered her scant comfort from the elements. The Hearst machinery tried to generate "a lot of heavy breathing" by noting that her "slight, dark-haired and piquant good looks attracted much attention on the train, and curiosity as to her purpose here is already deepening" (Motavalli, 191). A resident of New York City, she objected when the role required her to soil her hands and get them bloody. She backed out with only a week beneath her belt.

Settled in Washington

Once the dew evaporated from the rose of his national celebrity around 1917, Knowles chose to return to the visual art that had kicked his career into gear. Seaview, two miles north of Ilwaco, was a different kind of wilderness from the one that he had known in Maine. The Pacific could never be devastated by loggers or overrun by hunters and miners. The vagaries of the public eye by then had likely begun to weary him. Reports from Seaview in the ensuing years described him as pudgy, which photos show, like he was before his first excursion, when he etched himself as an Adonis sporting a couple dozen fewer pounds. One photo of Joe and Marion (Motavalli, 249) shows him in a painter’s frock fastened well below the knees. The hatted husband and wife, with their companion husky Mukluks, squint out through eyeglasses.

In 1923, Knowles was commissioned to create a series of oil paintings for the Monticello Hotel in Longview. These artworks, collectively titled The Winning of the West, consist of 42 murals that adorn the hotel’s lobby. Positioned above the mahogany wainscoting, the paintings depict pivotal scenes from the history of the Pacific Northwest, including the Whitman expedition and portraits of early figures such as John McLoughlin (1784-1857) of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Knowles completed these murals in 1925. His work contributes to the hotel’s Georgian Revival interior, enhancing its historical ambiance. Those murals remain a central feature, offering guests and visitors a visual journey through Washington’s past.

The married couple took in two other women to live with them and made a ménage. Both women were painters who helped Knowles complete commissions to meet the financial needs of his sunset years. Nellie Carney was an accomplished artist. Edyth Henry had come to study with him but soon thereafter became his able assistant. Both women allegedly had a loft above the detached garage, and all four shared one outhouse. No one knows the exact bonds that kept those four souls happy, nor do telltale records survive of community opinions about their strange arrangement. No Hearst was found buzzing around to create sensations or to tempt Knowles to further escapades. He recommitted himself to the visual arts and found commissions from hotels and government agents. A sign on his door read, "Joe Knowles the Nature Man, Etchings, Oils, Watercolors" (Motavalli, 212).

Few records remain of his early earnings. When he began to win sizeable commissions in Washington, he was filling four stomachs and satisfying his own appetite for costly automobiles, one of which he crashed with a load of friends while trying to race across a set of tracks and beat an oncoming train. His "finances were always up and down, with windfalls followed by long periods of penury" (Motavalli, 238). A windfall in 1925 contracted him to paint 12 Italianate panels for the 1000-seat Liberty Theater in Astoria, Oregon, designed by the architectural firm Bennes and Herzog. An Astoria newspaper made the claim that he "has traveled through Italy and spent considerable time in Venice, so has thorough, first-hand knowledge of his subject" (Motavalli, 240). The claim is ludicrous, like the many other claims that stretched the skin of truth till it squeaked, but he "could be a very convincing liar, and no doubt he told some very big ones to get this lucrative commission" (Motavalli, 241). Even so, "Knowles was a significant artist, whose work documenting the Washington coast is still highly regarded in the Pacific Northwest" (Motavalli, 153).

If his Bohemianism endeared Joe Knowles to people in positions to give him money, few would have faulted him as a free spirit, either in his domestic arrangements or in his willingness to shuck his clothes to advance his claims about nature. In early Washington, which earned its statehood in 1889 to become the 42nd state, he was a minor renegade. That word entered English from Spanish in the sixteenth century, where it originally signified an outlaw – someone who has turned away from or rejected an established authority, tradition, or system. As a showman of questionable but steady renown, Joe flouted the longstanding practice of truth in advertising.