Katharine “Kay” Bullitt was a prominent Seattle-based educational reformer, civic activist, and philanthropist. She attended private schools and graduated with a degree in government from Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After teaching elementary school for five years, she moved to Seattle around 1951. There she met her husband-to-be, attorney Charles Stimson (Stim) Bullitt, at a Democratic fundraiser in 1954. Stim Bullitt was heir to the Bullitt family fortune made in timber and real estate, but despite their wealth the couple eschewed the spotlight. For decades, they opened their home at 1125 Harvard Avenue E to friends and colleagues for summer picnics and welcomed groups as diverse as the Urban League, Save Pike Place Market, Japanese American Citizens League, and Common Cause. During summertime in the 1960s, Kay Bullitt organized an integrated day camp in her yard for children. Among her many causes were school desegregation, civil rights, the arts, historic preservation, and international understanding. In 1973, six years before the couple divorced, they deeded their home to the city to use as a public park after the last surviving partner died. That was Kay Bullitt, who died at home on August 22, 2021, at the age of 96.

Like Mother, Like Daughter

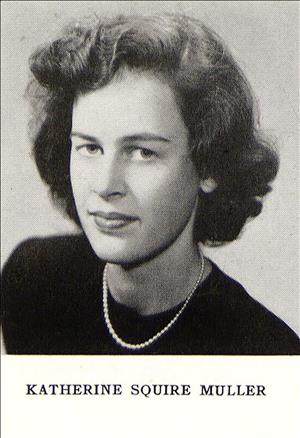

Katharine Squire Muller Bullitt (1925-2021), called Kay for much of her life, was born in Boston on February 22, 1925, and raised in the nearby suburb of Arlington, Massachusetts. She was the second of three girls (with siblings Marion and Margaret) born to William Augustus Muller (1867-1941), a real estate and insurance agent, and Marion Churchill (1885?-1976).

Bullitt’s father died while she was still a teenager. Her lifelong passion for educational reform, civil rights, and activism were likely inspired by her mother Marion, whose own career path was unusual for the time. Marion graduated magna cum laude from Radcliffe College in 1906 and received a Master of Arts degree in 1920 from Colorado College in Colorado Springs. She began her career as a high school teacher in the Boston area and later served as dean of women at Colorado College before marrying William Muller in her late thirties. Founder of the Radcliffe College Alumnae Association, she also established the Arlington Visiting Nurses Association and was president of the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union of Boston.

Daughter Kay attended Shady Hill School in Cambridge, went on to Concord Academy, and then attended her mother’s alma mater, Radcliffe College, where at one point she worked in a community center that served Black youth. In a break during the summer of 1944, she joined the Hampton Institute, an historically Black college in Hampton, Virginia, where she was part of an interracial farm project tasked with growing food for the war effort. It was here that Kay got an up-close look at the realities of racial segregation. The experience intensified her interest in activism and civil rights.

Even as a student, Kay Muller stood out among her peers. Journalist Sam R. Sperry wrote: "Whether it was her part in the triumph of the women’s eight-oared crew that defeated the Harvard men, or catching the recognition and admiration of the future Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Thomas P. (Tip) O’Neill, when she testified, as a student, in support of Fair Employment practices before the Massachusetts Legislature or, social convention notwithstanding, choosing to join a summer program for young African American women – Kay just did it" ("Making Waves …").

After earning a bachelor’s degree in government, with a thesis on the role of the federal government in education, she became a fourth-grade teacher at her former elementary school, Shady Hill, a post she kept for the next five years. During that time, she took a cross-country trip to study how children in other parts of the nation were being trained to enter the work world. To prepare for her journey, she talked with educators and others, including cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978), whom she visited in New York.

Seattle and Marriage

Kay Muller left Massachusetts around 1951 for Seattle, where she quickly made friends with like-minded women. The list included Eleanor Siegl (1917-1996), who founded The Little School in 1959, one of the first alternative pre-schools in Seattle (of which Bullitt served on the board of trustees), and Dorothy Block (1925-1961), who championed numerous youth organizations and served on the Seattle Board of Parks Commissioners. It was Block and her financier husband Robert who introduced Bullitt to her future husband at an Americans for Democratic Action meeting in 1954.

At the time, Seattle attorney Charles Stimson (Stim) Bullitt (1919-2009) was in the middle of making a run for Congress – his second, unsuccessful attempt. The grandson of a wealthy Pacific Northwest lumberman and real estate developer and the son of a lawyer and politically active statesman with roots in Kentucky, Stim Bullitt was educated at Yale and the University of Washington. During World War II, he served in the U.S. Navy and was wounded in the Philippines. His mother Dorothy Stimson Bullitt (1892-1989) was a savvy businesswoman who founded KING-TV in 1949, the first woman in the U.S. to buy and manage a television station.

Stim Bullitt was taken with Kay from the start and was said to have proposed within two weeks of their meeting. The wedding took place on November 27, 1954, at the historic Old South Church in Boston, with a reception at the Shady Hill School where Kay had once taught. This was Bullitt's second marriage. His first was on January 24, 1948, to Carolyn Ashley Kizer (1925-2014), a well-regarded, and later Pulitzer Prize-winning poet from Spokane with whom he had three children. She filed for divorce less than six years later, on December 1, 1953, citing cruelty and personal indignities. Kay agreed to help raise their three children – Ashley, Fred Nemo, and Jill. Kay and Stim had three more children: Dorothy, Margaret, and Benjamin. Benjamin (1957-1981) died at the age of 24 while sailing on his brand-new boat on Lake Washington. His body was never found.

The Home on Harvard Avenue

In 1952, Stim Bullitt acquired nearly two acres of land on Seattle’s Capitol Hill near Volunteer Park. Much like the Bullitt family itself, the property was steeped in local history. An earlier house on the lot had been built in 1893 by Seattle pioneer and railroad magnate Horace Chapin Henry (1844-1928), who later donated his art collection to the University of Washington to form the Henry Art Gallery. After his death, the Henry heirs donated the land to the city for a library. The city demolished the existing house but then decided to build the library elsewhere. Lumberman Julius H. Bloedel (1864-1957), who lived next door, purchased the empty lot, which was later sold by his son Prentice Bloedel (1900-1996), founder of the Bloedel Reserve on Bainbridge Island, to Stim Bullitt in the 1950s.

Bullitt hired Seattle architect Fred Bassetti (1917-2013) in 1955 to design the house at 1125 Harvard Avenue E. Bassetti, a leader in midcentury-modern design with a distinctly Northwest aesthetic, created an unusual A-frame home on the site, complete with skylights, open floor plan, and massive stone fireplace. The house was reminiscent of a ski chalet, a style said to be favored by Stim, who loved skiing and the outdoors. San Francisco landscape architect Garrett Eckbo (1910-2000) was retained to create the landscaping.

Kay Bullitt lived in the Harvard Avenue home for the next 66 years, long after she and Stim divorced in 1979. Every Wednesday in July for more than six decades, she threw open the doors of her home and yard to host a picnic for family, friends, and colleagues, which often drew hundreds of guests. She firmly believed: "When you bring people together around a purpose, good things happen" ("Making Waves …"). This sentiment was borne out by scores of meetings, fundraisers, brainstorming sessions, and political campaign events held on Harvard Avenue.

Focus on Education and Civil Rights

Throughout her life, Bullitt put the full force of her energies, enthusiasm, and resources to work, helping to create change and build better futures for those less fortunate. Historian Chrisanne Beckner explained:

"While Stim was involved in law, politics, real estate development, and management of the King Broadcasting Company in the 1950s and 1960s, Kay often worked, with and without her husband, to cement relationships, build coalitions, and conduct civic actions from her home at 1125 Harvard Avenue E. Kay was an outgoing and well-connected activist who, like other members of the Bullitt family, was interested in philanthropy. Her priorities included peace activism, racial equity, education, music, and the advancement of women in business" (Seattle City Landmarks Nomination, 21).

Her theory was that incremental change, even by one individual, can lead to great advances. For three decades, she advocated for the desegregation of Seattle schools. Her civil rights activities took many forms – from supporting school busing to hosting an integrated day camp during the summer months at her home. In 1967, she co-founded the Volunteer Instruction Program (VIP), to assist public school teachers in Seattle’s Central District. In 1969, she participated in a protest walk to Olympia to persuade Washington legislators to allocate more funding to public schools. She helped organize the Coalition for Quality Integrated Education, a desegregation-focused nonprofit, in 1971 and served as its president until 1974. She took an active role in many other education groups including Seattle’s Say on Schools and Citizens Education Center Northwest.

In 1979, Bullitt helped create an innovative school-business partnership called PIPE, or Private Initiatives in Public Education. Modeled after similar programs in Dallas and Minneapolis, PIPE matched people from the business community with educators from each of Seattle’s 12 high schools. The partners worked together to identify ways to better prepare students for the work world – arranging for students to shadow workers on the job or commandeering local business leaders to help guide curricula development. Bullitt was a PIPE board member from 1979 until 1986.

Her nonstop commitment to education was lauded by many, including Norman B. Rice (b. 1943), who during his term as Seattle mayor in the 1990s said of Bullitt: "I’ve never met a person who was so committed to education in the community … Her influence was far reaching and deep" ("Kay Bullitt, Seattle Philanthropist …").

Art, History, and World Peace

Bullitt also worked to advance civil rights and women’s rights, historic preservation, and environmental awareness. As she noted in an interview with the Post-Intelligencer:

"If you get on one path, you have to keep following it … The trouble is, I have too many paths. But as I look back over my life, I’ve been consistent in my interests – education, civil rights, historic preservation, the environment, international understanding and peace and the arts. They are important social issues to me – and there’s still a lot to do" ("Winner of 1983 Award …").

Bullitt’s interest in historic preservation was sparked by a newspaper article that she read in her thirties. The story centered on an historic schooner called Wawona, built in 1897 in California that was deteriorating on a South Lake Union pier. Acting with other civic leaders including Seattle City Councilmember Wing Luke (1925-1965) and restaurateur Ivar Haglund (1905-1985), Bullitt helped found Save Our Ships, an organization to raise funds to restore the vessel and repurpose it as a museum. Thanks to the group’s awareness-building tactics, Wawona was named a National Historic Site in 1970, the first ship in the country to be listed on the National Register.

The ship’s restoration costs proved prohibitive and after 46 years of fundraising and volunteer outreach, the painful decision was made to dismantle the vessel. Before that happened, a team of maritime archaeologists thoroughly documented the ship in 2009, and officials at the Museum of History and Industry commissioned artist John Grade to create a 65-foot sculpture for their atrium using some of the schooner’s wooden planks. Although disappointed, Bullitt tried to put a positive spin on the decision: "I really felt, after all this time, that all the preparation to move her, the documenting efforts, the move, was a real example of death with dignity" (“Once Proud Vessel Can’t Be Saved …").

In 1971, Bullitt was appointed to a team to create the Mayor’s Arts Festival. The event was a success and led to Bumbershoot, the annual Labor Day music and arts festival held at Seattle Center a few years later. She was actively involved in saving Pike Place Market, which had been targeted for demolition. Bullitt was an inaugural member of the Pioneer Square Historic Preservation Board charged with preserving and protecting the historic and architectural character of that neighborhood, a post she retained from 1971 until 1982.

As the first president of the Historic Seattle Foundation, Bullitt supported the completion of the Good Shepherd Center, which included space for community groups and affordable housing for artists, and she campaigned to acquire the Third Church of Christ Science (now Town Hall Seattle). She raised funds to repair the Cadillac Hotel, damaged by the 2001 Nisqually earthquake, which became home to the Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park.

Bullitt was a long-time board member of BlackPast.org, a website promoting African American history. As part of her push to end discrimination, Bullitt co-founded Sound Savings & Loan in 1977, a bank financed and operated mainly by women for women. She demonstrated against the Vietnam War and in the 1980s helped organize the "Target Seattle" antinuclear protests.

Bullitt received many awards and citations, including the Jefferson Award for Public Service, YMCA Milnor Roberts Award for World Peace through International Understanding, United Nations (Seattle Chapter) Human Rights Award, Paul Beeson Award from the Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility, Lifetime Achievement Award from the Metropolitan Democratic Club, and Seattle Bar Association’s Ralph Bunche Award. Along with other Bullitt family members, she shared the 2000 Seattle King County First Citizen Award.

Later Years

After nearly 25 years of marriage, Kay and Stim Bullitt divorced in 1979 although Stim had moved out three years earlier. The couple remained close for the next 30 years until his death in 2009, often celebrating family birthdays and important milestones together. In 1973, six years before the divorce, they decided to donate their house and the 1.6-acre parcel on which it sat to the City of Seattle to create a public park upon the death of the last surviving resident.

In her later years, Bullitt kept busy with committee meetings and events, interspersed with taking her dogs on leisurely walks around her Volunteer Park neighborhood. She had always loved the outdoors and as a young woman had enjoyed swimming, boating, hiking, and tennis. Well into her eighties, she would rise at 7 a.m. for a morning aerobics class before putting in a full day of appointments, board meetings, and fundraisers. In her "down" time, she read three newspapers a day.

Bullitt’s home and yard continued to be a hub for friends and colleagues to gather and relax as well as to come together to discuss ways to solve some of the city’s most divisive issues. Historian Chrisanne Beckner observed: "In her later years, when she was less active and mobile, Kay even offered up her large yard as a place for local dogs to play, both so that she could watch them from her window and so that newcomers and people living in apartments had a place to run their pets" (Seattle City Landmarks Nomination, 23).

Kay Bullitt died peacefully at the age of 96 on August 22, 2021, in her home on Harvard Avenue, supported by family members and a team of caregivers. In accordance with the Bullitts's wishes, the City of Seattle acquired the house and grounds in December 2021. At a public meeting on July 19, 2023, Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board designated the property as a historic landmark and began a series of community meetings and surveys to get input on how best to create a public park. A segment of the Bullitt property was expected to open to the public in late 2025 with full park access estimated in 2029.