Intensive logging started later in Southwest Washington than it did around Puget Sound, largely because sandbars at the mouths of the Columbia River, Willapa Bay, and Grays Harbor impeded the passage of heavily laden schooners. But when loggers did begin cutting the forests of the Black, Doty, and Willapa hills; the Chehalis, Cowlitz, and Columbia river basins; and the foothills of the southern Cascades, Washington quickly became the nation's top wood producer. In the 1980s and 1990s, the depletion of old growth forests on privately owned land and new restrictions in federal and state forests led to sharp declines in logging, which had repercussions throughout the region. But Southwest Washington has been recovering as its residents have begun forging a new relationship with the forests in which they live.

The Original Inhabitants

The magnificent forests of Southwest Washington began to take shape after the last great Ice Age loosened its grip on the Pacific Northwest. About 16,000 years ago, at the peak of the glaciers' southern expansion, an observer standing at the site of Tenino would have looked north to an immense rampart of ice rising to a height of more than 3,000 feet. To the northwest and east, massive glaciers crowned the Olympics and Cascades, with rivers of meltwater scouring gravelly outwash plains. The landscape looked more like northern Canada than today's Western Washington.

By about 15,000 years ago, the ice lobe between the coastal ranges and Cascades had retreated to around the Canadian border. Over the next few millennia, plant and animal communities expanded across southwest Washington from scattered Ice Age refugia. By about 9,000 years ago, the forests of the region contained species that are common today, with a mixture of red alder, Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock in the lowlands. (Western redcedar moved into the area from the south somewhat later.) Subalpine species like silver fir and Engelmann spruce, previously found in the lowlands, grew on the flanks of Mount Rainier, Mount Adams, and Mount St. Helens and near the Cascades crest.

The post-glacial period of warming was when Native Americans began to occupy the region. According to one hypothesis, the first humans to enter the interior of North America may have moved up the Chehalis River after migrating southward along the coast from Asian homelands, since massive ice sheets would have blocked passageways to the interior farther north. Though much more archeological research is needed, Southwest Washington could have been the point of entry for humans into a previously uninhabited continent.

Native Americans made extensive use of the forests around them. They made structures, canoes, and masks from Western redcedar and used the tree's bark for baskets, mats, clothes, and hats. They set fire to the forests and brush to boost the growth of berries, clear the ground for crops like camas, and increase browse for the animals they hunted. The result was an "anthropogenic landscape" in the words of ethnobiologist Nancy J. Turner (b. 1947): "mosaics of geographic and ecological regions and sites where people participate in diverse ecological processes ... which are interconnected in a seamless web of natural and cultural processes that extends across generations and millennia" (Turner, 217).

The Arrival of Europeans and Americans

The first European and American explorers to see the forests of the Pacific Northwest were astonished at their scale and scope. In June 1788, the English fur trader John Meares (1756-1809) wrote of the forests: "The timber is of uncommon size, as well as beauty, and applicable to any purpose" (Meares, 239). One American pioneer remarked in his diary that the trees of the Northwest were "so thick tall and straight that it must be seen to be believed" (Ficken, 4).

The newcomers would eventually transform the forests of the Northwest, but their greatest initial impacts were on the region's people. Smallpox spread by sailors killed an estimated 30 percent of Native Americans in coastal communities during an epidemic that began around 1781. Later and repeated epidemics of smallpox, malaria, measles, influenza, whooping cough, cholera, and other diseases may have reduced the numbers of Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest by 90 percent.

The earliest settlers in the Pacific Northwest used hand-powered whipsaws to cut planks for houses and other structures. The region's first sawmill, built by the Hudson's Bay Company six miles up the Columbia River from its Fort Vancouver outpost, began operating in 1828. Lumber from the mill, in addition to being used locally, was sold as far away as California and Hawaii.

By 1860, more than 20 sawmills were operating on Puget Sound, where calm waters and deep harbors facilitated the loading of spars and sawn lumber onto schooners bound for markets as far away as Peru and China. The lumber industry was slower to develop in Southwest Washington because of the treacherous bars at the mouths of the area's three harbors – the Columbia River, Shoalwater Bay (later Willapa Bay), and Grays Harbor. The first mill on Grays Harbor built to serve the cargo trade did not begin operating until 1882, right before a major transition for logging in the Pacific Northwest.

The 1888 completion of the first transcontinental railroad to Washington Territory through a tunnel over Stampede Pass provided a new way to ship lumber to Midwestern and Eastern markets. At the same time, railroad technology opened vast new realms of the forests to logging. Previously, trees within a mile or two of the shoreline were cut down and then dragged on skid roads by oxen, horses, or donkeys to the water, where they were floated to sawmills or waiting schooners. Logging railroads extended the reach of loggers into the woods by an order of magnitude. The first logging railroad in Washington Territory was built near Tenino in 1881, and by 1887 the territory had 107 miles of logging railroads. Meanwhile, the proliferation of the recently invented steam donkey made it possible to drag felled logs from much farther away to landings. Double-bitted axes, steamships (including tugs to tow schooners into and out of bar harbors), improved saws in the woods and in sawmills, and high-lead logging all added to the technological and human juggernaut.

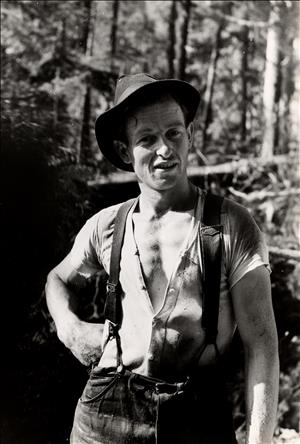

By the first part of the twentieth century, Washington loggers were swarming over some of the greatest forests on earth. They worked their way up the drainages coming off the southern Olympic Mountains and the Black Hills southwest of Olympia. They reduced tracts of the Willapa and Doty hills, which are bounded by the Chehalis, Cowlitz, and Columbia rivers, to muddy clearcuts. They made their way east and north from the Cowlitz and Columbia rivers toward the foothills of the Cascades, sending logs in gigantic rafts downriver to the waiting mills. Logging "paid the bills, bought property, and provided a fragile sense of security" to a growing workforce of loggers in Southwest Washington, as James LeMonds of Castle Rock wrote in his book Deadfall: Generations of Logging in the Pacific Northwest (LeMonds, 1).

Land Acquisition

The intensity of logging in the Pacific Northwest reflected the depletion of forests elsewhere. By the end of the nineteenth century, Midwestern timbermen were turning their attention away from the cutover white pine of Wisconsin and Minnesota toward Washington and Oregon. The most consequential purchase of timberlands occurred on January 3, 1900. Frederick Weyerhaeuser (1834-1914), who had built an industrial behemoth after his 1860 purchase of a small Mississippi River sawmill, announced that he was buying 900,000 acres of timberlands from his St. Paul neighbor, railroad baron James J. Hill (1838-1916). Hill had come to control the land grants of the Northern Pacific Railway. At that time, the Northern Pacific held more than 7 million acres of land in Washington (almost 20 percent of the state's total area). The property came from the land grants it had received for building rail lines from Kalama north to Tacoma (the rail line that parallels Interstate 5 today) and from Spokane through Pasco to Tacoma. In subsequent years, Weyerhaeuser bought more land from the railroad and from other owners, becoming by far the largest owner of land in Southwest Washington.

Many other public and private entities were also acquiring land in the region. Upon becoming a state in 1889, Washington received more than 3 million acres of land to support public schools and other services, and it subsequently acquired more land through tax foreclosures, purchases, and gifts. Timber companies and individuals bought timberland to log or hold as an investment. Metsker maps from the 1930s and 1940s, which show ownership of sections and sub-sections of land, testify to the very wide range of property owners in Southwest Washington.

Not all Americans were eager to see the forests of the Western United States reduced to stumps by ambitious and increasingly wealthy timbermen. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, a budding environmental movement contributed to the creation of forest reserves withdrawn by the federal government from settlement. The Pacific Forest Reserve was created in 1893 to protect land around Mount Rainier. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot, chief of the Forest Service, created the Rainier National Forest along the Cascades range. The next year the southern portion of this area, from south of Mount Rainier National Park (created in 1899) to north of the Columbia River, was separated out as the Columbia National Forest. In 1949, the area was renamed the Gifford Pinchot National Forest to honor the Forest Service's first chief.

Getting Out the Cut

By the early 1900s, as wood began to pour out of the forests of Southwest Washington, the state had become the nation's leading lumber producer, a position it held until being overtaken by Oregon in 1938. Rapid expansion of the pulp and paper industry after World War I created additional demand for timber, including the less desirable hemlock that loggers had often left to rot in the woods. At one point, Grays Harbor and the adjoining Chehalis River had 46 sawmills and other wood-processing plants and 33 docks that could handle 55 ships at a time. In 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took his Spirit of St. Louis on a national tour, he tipped his wing to the Hoquiam mills that had manufactured his airplane's spruce wing spars and ribs.

The timber industry experienced good times and bad in the twentieth century as war, economic depression, and labor unrest (including a gun battle between pro- and anti-union forces that left five men dead in Centralia) had both direct and indirect consequences in Washinton's forests. The good times were exemplified by the Long-Bell Lumber Company's opening of a major manufacturing complex in 1924 where the Cowlitz River joins the Columbia, along with construction of the nearby planned city of Longview with room for 20,000 employees and their families. The bad times were exemplified by the same company's severe financial difficulties less than a decade later during the Great Depression.

After World War II, the assault on the woods heightened. Trucks and tractors largely replaced logging railroads and led to the construction of many thousands of miles of logging roads in Southwest Washington forests. Chainsaws made it possible for a single logger to fell and buck trees faster than an entire crew using axes and crosscut saws. The demand for plywood and fiberboard to build houses swelled after the war, and the export market boomed. By the 1960s, one in seven jobs in Washington was related to logging and lumbering.

By that time, much of the private land in Southwest Washington had been logged at least once. Some companies and individuals were willing to hold onto their land and wait for the forests to regrow. Weyerhaeuser, for example, established several large tree farms on cutover land where it applied intensive forestry management to plant, fertilize, cull, and then harvest successive generations of trees. Other companies sold their land or let it revert to public ownership.

The inevitable wait for forests to regenerate put increased pressure on the federal and state governments to open public lands for logging. After decades of being largely a caretaker of the national forests, the Forest Service entered a new period in which it not only permitted but encouraged extensive logging of public timberlands. Aerial photographs of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest revealed as many clearcuts as in nearby privately owned forests. Communities throughout Southwest Washington became economically dependent on a steady supply of logs from not just private but public lands.

The Boom Ends

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens coincided with a watershed period in Southwest Washington. After a century of logging, the primordial forests of the region were almost gone. Private companies, including Weyerhaeuser, were cutting the last of their old growth, after which it planned to shutter its mills that could handle big trees. The economy of the Pacific Northwest was diversifying, so fewer people depended on the woods for their incomes. And a rapidly growing environmental movement was pressuring the federal and state governments to reduce logging and protect the forests from further road building and development.

All of these forces intensified over the course of the 1980s. In response to the demand for wood, the Forest Service and Washington State Department of Natural Resources increased sales of timber from public lands, which led to further protests from environmentalists. More and more people came to the woods to hunt, fish, hike, backpack, snowshoe, snowmobile, ride horses, and camp, and many of them decried the wholesale cutting of trees. Forest researchers increasingly recognized and publicized the value of mature forests in providing societal benefits other than wood.

In 1990 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service approved adding the northern spotted owl to the list of species protected under the Endangered Species Act. The next year United States federal district court judge William L. Dwyer (1929-2002) issued injunctions blocking timber sales and logging on federal lands pending development of a plan to protect the owl. The Northwest Forest Conference held in Portland in April 1993 led to the creation of the Northwest Forest Plan, which protected old growth and "late successional forests" as well as the species that depended on those forests. The listing of several salmon species as endangered in 1998 led to further restrictions on logging.

Constraints on logging in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, along with the depletion of timber on private lands, caused timber harvests in Southwest Washington to plummet. Across the region, loggers lost their jobs, mills shut down, businesses related to logging and lumbering shuttered, and people began to move elsewhere. Fewer timber sales on public lands led to a decline in tax revenues. Ranger stations began to close, washouts on logging roads went unrepaired, and public amenities deteriorated. Service jobs associated with tourism and recreation partly compensated for job losses in the timber industry, but such jobs paid far less than jobs in the woods and mills had paid.

A Renewal

The forest-products industry in Southwest Washington will likely never again be as large or vibrant as it was during the twentieth century. Most of the area's old growth is gone, and the old growth that is left has more protections than in the past. Though controversies continue to surround the cutting of land overseen by the Washington State Department of Natural Resources – particularly the older forests – the department more closely regulates the cutting of timber on its own land and on private land. Native American tribes are more involved in the management of the forests. Researchers are adding to the inventory of benefits that older forests provide. Environmental groups continue to monitor timber sales and object to ill-advised logging.

Nevertheless, the wood-products industry has survived and in some cases is thriving. Weyerhaeuser and other logging companies are raising a second, third, and even fourth generation of trees on the land that they own. Innovative logging companies have brought new approaches to the harvesting of wood, such as conservation easements that maintain working landscapes. The 110,000-acre Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, created in 1982 after the eruption, attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors annually, though Forest Service cutbacks have constrained the visitor experience. Controversies over cutting cycles, the use of herbicides on tree farms, carbon retention, the logging of older trees, and forest access continue. Given the many and often competing demands people make of forests, these controversies will persist.

Overall, the forests and the communities of the region are recovering from the bust of the 1990s. Between 2010 and 2025 – even excluding the fast-growing city of Vancouver – the population of Southwest Washington (Clark, Cowlitz, Grays Harbor, Lewis, Pacific, Skamania, and Wahkiakum counties) grew by 17 percent. People no longer flock to the region to log or work in the mills. But the rain-washed trees, misty hillsides, and hardy communities exert a powerful attraction. As long-time Grays River resident Robert Michael Pyle wrote in his paean to the Willapa Hills, Wintergreen: Rambles in a Ravaged Land: "When the mills close, the log trucks stop rolling, the dairies go to summer beef or weeds, wet green remains the same" (Pyle, 333).