Priscilla Maunder Kirk (1898-1992), an African American Seattleite, was born on August 9, 1898, in Seattle. In 1919 she moved to Montana with her husband, where she lived until 1929. She also lived in Minnesota before returning to Seattle in 1955. This is an excerpt of an oral history interview of Priscilla Kirk done by Esther Mumford on June 18, 1975, as part of the Washington State Oral History Project. Priscilla Maunder Kirk died on November 14, 1992.

Excerpts From the Interview

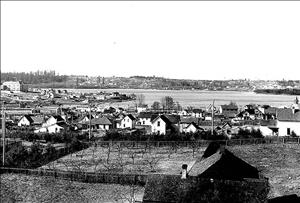

"My early years were spent in the Green Lake district of Seattle, that’s one of the northern parts of Seattle. My father had purchased the land there in 1900, and built our home. The homeplace is still standing, although it is not in the family possession. We attended the Green Lake public school … through the eighth grade, then I entered Lincoln High School from which I graduated in 1916.

"When we first moved into Green Lake, my father was able to buy a quarter of a block for $500. And I can remember going to Green Lake school through cow paths and wooded areas, old rickety sidewalks. It was built up and began to … oh, become populated, and the streets were graded and paved and paved and paved -- sidewalks. But that didn’t even happen until I would, say 1911 and 1912.

Rickety Sidewalks, Rickety Streetcars

"[Before] they were old wooden, rickety sidewalks and dirt streets. Our home was on 59th and Kensington Place, and if you ride the bus now, the bus runs, comes right down Kirkwood Place, just one, within one block of our old homestead, down to the lake. We lived just five blocks just from the lake.

"Our home was built out in Green Lake, around 1904 or ’05 ... at that time there were street cars that came from the downtown area around East Lake, around … Lake Union past Boeing’s little old plant ... 1916 ... they had opened up this here Boeing plant on Lake Union in 1916. And we used to drive around, these rickety street cars aro und Lake Union out over the Fremont Bridge, and around through …the street car circled the lake, completely. Through the middle of Woodland Park and back on down into the city, into the central Seattle area city. The Aurora Bridge was built, oh around in … I would say 1915, ’16 maybe ’17. I can remember them constructing that bridge … I hadn’t finished from high school.

"We used to ferry across Lake Washington, on a ferry boat to Kirkland. And as kids that would be one of our great day outings. We would get on the ferry boat, down there at Leschi beach, and ferry across to Kirkland. So when I returned in 1955, why the Mercer Island Floating Bridge was a novelty to me, in fact some of them told me it was one of the Seven Wonders of the World. It was because they told me it was built on concrete pontoons. That was quite a novelty.

Limited Opportunities for Blacks

"I took a college preparatory course ... [including credits] in History, English, Foreign Language. So I was prepared for college although I was not able to attend … because I had a sister who was three years younger. And my father thought that she should be given the opportunity to finish out the high school. Therefore I obtained the job, which was a menial job, but which was practically all that was open to the black, at that present time.

"I worked as a maid in the parlor of the Moore Theater, which was quite a popular theater house at the time. I worked for a Jewish man by the name of Mr. Ritter. It was a theater that ran shows I would say, shows that came into the city, probably traveling shows. I worked in the, as I say, lounge, where the people would come for powdering … just a menial job.

"From then, from there I moved over to ... receptionist and attendant at the Ohio Dental Parlor, which I thought was quite a promotion. This was down on 5th and Seneca … I just recall the name of Miss Darwell, it was Jane. Jane Darwell. Maybe many of you have seen her in some of the old-time movies ... I stayed with the Ohio Dental Parlor almost two-and-a-half years.

"When I left Seattle [in 1919], 85th was the boundary line at the north. And it had been extended to 145th, city limits. And that was quite shocking. Seattle had grown … oh, in all dimensions. I can remember where Sand Point is now, we use’ to go around there and pick blackberries, around the lake there, blackberry patches and here it was Sand Point Naval Station. It had just grown by leaps and bounds the boundaries in every direction.

"Just to think ... back in those years ’17, ’18, ’19, the young [African American] men were elevator boys in the stores. They were waiters in fabulous Washington Hotel, which is now the Josephinium Catholic Retirement Home. The majority of the men ... if they didn’t work as mail carriers. Not very many clerks … in the post office. You carried mail on the streets … there were quite a number of exclusive barbershops owned and operated by old timers, but they catered to white clientele. Downtown establishments, yes.

"The work ... I didn’t realize the conditions that were kept back [then], as to employment until I came back on a visit in 1944. And I was told that we had black school teachers. Well my eyes were just opened. I didn’t know ... well how did it come about? We had no teachers. We had, in fact there was no job openings for us, outside of those menial jobs. You could work at the docks, you could work on the boats. The Alexander Boats. Cruising, and it was for the better class, it wasn’t for blacks. It was for the better class of white people, but they had black help. Cooks, waiters, and whatever they hire on the boats. But that did afford a livelihood for a number of young men.

The Great War

"[During World War I] ... I have an older brother George ... and ... he was drafted for the first, for World War I and was stationed in Fort Lewis. I don’t know where they brought in these young men from, I guess from parts up and down the coast. But anyway they were recruited and brought up to Fort Lewis. And from there left to go overseas. My brother went overseas and was stationed in France.

"I treasure a postcard that he had mailed from France, 'Somewhere in France' it says. 'World War One, 1918.' My brother was very fortunate. He had attended a business school after graduating from Lincoln High School. And he was able to work in the headquarters while stationed overseas. And came back safe after the war was over and is still living in California. He went into the ministry. And is an ordained C. M. E. pastor, and has a little 'Mission by the Side of the Road' in Pacoima, California, George Hartwell Maunder, Reverend.

"The days of getting prepared for this World War I ... There was a small group of women who organized a club, it was called the Self Improvement Club. And those women knitted socks and did what I would call Red Cross work. A very very dedicated group of women. They corresponded with the boys and sent packs to them, cigarettes, those [African American] boys going over in World War I weren’t treated like the boys maybe in World War II. They were discriminated against. This I know to be a fact.

"They, lots of things that came over there through the Red Cross and organizations like the Self Improvement Club, and other groups who organized and sent to the boys individually, they wouldn’t receive packages, you know, from home. I have heard my brother tell about packages arriving and being bypassed, by different things that came, through organizations other than black organizations ... they were passed by.

"But nevertheless the boys went over and did their duty, and they came, majority of them came back safe and sound. I never will forget the day when those boys returned. I was working in the Ohio Dental Parlor, and they had a march down 2nd Avenue. And everybody in the Ohio Dental Parlor quit work and lined up in the windows to watch the boys come marching home. It was a very, very, very ... well it was a day of rejoicing, it was yes, I should say, an emotional day.