Just before dusk on July 2, 1881, Seattle receives the following news in a Washington D.C. telegraphic dispatch: “The President is dead. He died at 4 o’clock this afternoon.” The message has taken seven hours to get across the continent. Seattle residents immediately start mourning the assassination of U.S. President James A. Garfield (1831-1881). Two or three hours later, a second telegraph dispatch is received with the news that the President is still alive. The President will live for 80 more days before succumbing to his wounds.

News Flash by Telegraph

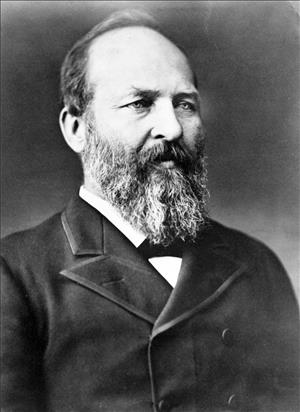

President James A. Garfield had served as the 20th president of the United States for just four months. On July 2, 1881, at 9:26 a.m. (about 6:26 a.m. Seattle time) Garfield was walking through a Washington D.C. railroad station to board a train. Suddenly two shots rang out. One hit the president’s arm and the other lodged in his lower back. Police officers immediately arrested assassin Charles J. Guiteau (1841-1882). The wounded president was taken to the White House to be cared for.

After the telegraphed news of the president's demise reached Seattle at about 8 p.m. on July 2, the word quickly spread. Within an hour, even though darkness was descending on the town, most of the business houses, halls, and many residences were draped in black crepe paper as a sign of mourning. The Daily Intelligencer reported that after receiving the melancholy news, "the town bore a death like silence. Friend passed friend with a silent nod, and a sad expression was depicted on every countenance."

The President Lives, But Not for Long

Then “late in the evening,” probably between 10 and 11 p.m., Seattle received a second dispatch, datelined Washington, D.C. 5:30 p.m.:

“The report of the President’s death is contradicted. He has just wakened from a short nap, and there is still a possibility of his recovery.”

Even at the late hour the news “spread like wildfire” and the crepe draping Seattle’s buildings “came down very rapidly.” The Intelligencer went on to say: “Let us hope for the best, and trust that Mr. Garfield may speedily recover, and long rule over the people that love and honor him” (Intelligencer, July 3, 1881, p. 3).

The Intelligencer editorialized:

“The President had been twice shot and dangerously, if not fatally, wounded … Such acts are fearfully ominous. They shock the sensibilities of the people, make them doubt the efficiency of self government and produce a feeling of uncertainty and unrest. Such acts … strike the foundations of civil government with a shivering and deadly blow. Strong men when they read them or hear of them involuntarily hold their breath and ask, What next? We can only distantly gather and tremble at the ultimate consequences of such diabolism” (Intelligencer, July 3, 1881).

The President’s speedy recovery was not to be. The bullet wounds did not heal. Days of the President’s incapacitation turned into weeks and then months. On September 19, 1881, after 80 days, James A. Garfield finally succumbed to his wounds. He was the second president of the United States to be assassinated while in office, Abraham Lincoln being the first. The crepe paper on Seattle’s buildings reappeared.

Other areas of Washington mourned as well. On November 29, 1881, Garfield County -- named after the president -- was formed in Southeastern Washington by an act of the Washington Territorial Legislature. The original Garfield County stretched east to the Idaho state line; in November 1883, another act of the Territorial Legislature would carve Asotin County out of the eastern portion of Garfield County.

The Assassin

Apparently Garfield had denied the assassin, Charles Guiteau, an appointment as U.S. Consul to Paris. Some claimed Guiteau’s motive was revenge, others that he was a religious fanatic and that God told him to kill Garfield. The Weekly Ledger (Tacoma) described Guiteau as:

“[A] foreigner by birth ... an irresponsible, obscure, pettifogging lawyer, who cheated his clients, failed of success, turned beggar for office without political support, stole stationery from the White House ... was turned out of his boarding house for non-payment, and who did a number of absurd things for some time previous to his assault on the President.”

He pled guilty by reason of insanity. Within a year of shooting the President, Charles Guiteau was tried, convicted, and hanged.

Corrupt Patronage System Protested

In 1881, the Federal government employed about 100,000 civilians. Nearly all of those jobs were more or less political patronage appointments. Each winning president would spend the first weeks of his administration replacing the previous administration’s job holders with supporters of the new administration’s political party. But after Garfield's assassination, universal patronage appointments would come to an end. After it came out that one of Guiteau’s motivations was revenge for not receiving a patronage job, there was an enormous outcry against the spoils system of hiring.

The outcry came even from distant Seattle, which, because the town was still located in a territory, had no say in national politics. Upon the death of President Garfield, Seattle’s post of the Grand Army of the Republic unanimously passed a resolution memorializing the president’s death. The resolution of this Civil War veterans organization included the following:

“[W]e pledge ourselves anew to our country; and, as soldiers and citizens ... we demand that the spoils system in politics — the greedy scramble for office — the ... remote, if not the immediate cause of the President’s assassination, be rooted out” (Intelligencer, September 25, 1881).

By January 1883, in response to the national outcry, Congress passed the first federal Civil Service Act. It required that a portion of the civil service jobs be awarded based on ability and merit. This program started out small but over the years slowly expanded. In the 1990s, 99 percent of federal employees hired by the Executive Branch are hired under the guidelines of the Civil Service Act.