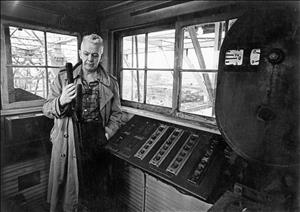

This reminiscence of Murray Morgan (1916-2000), the preeminent Northwest historian, is by Paul Dorpat, HistoryLink's principal historian, and an old friend of Murray Morgan's.

Murray Morgan

Murray Morgan (1916-2000) was fond of noting that he was blown in with the Big Snow of 1916. Eighty-four years and a few months later, he died in the early morning of June 22, 2000. The heart that had weakened him, especially in the last year, stopped. For his friends and readers the loss was similar. Murray shared his great gift for storytelling, both in his books and at dinner. Murray thought of himself more as a reporter than historian, although his many histories were well researched, often with the help of his librarian wife and sometimes co-author. Murray claimed that Rosa had uncanny powers of investigation, entering cavernous warehouses like the national archives and finding exactly the right stuff, often in uncatalogued boxes.

Murray generally liked the persons he wrote about. That they were also often flawed was a sign of both his realism and compassion. When I interviewed him for public television in 1987, Murray claimed that his greatest pleasure as an author was returning voices to those who were no longer heard.

As an example he noted the suffragette and firebrand populist Mary Kenworthy. In his book Skid Road Mary again fights the railroads and pursues monopolists in the 1880s, but this time also before the thousands who have read what has been the best-loved history of Seattle. Since its was first published in 1951 in time for the city's centennial. "Skid Road" has never been out of print.

Both of Murray's parents were writers, his mother of children's literature and his father, a Universalist Unitarian minister, of poetry and inspirational oratory. Murray was not always comfortable with the effects his father¹s considerable charm had on a large and often adoring flock, so the son shaped himself with irony, humor made often at his own expense, and a manner that was both forthright and whimsical at the same time.

Murray was a great wit. His hair was wild, he shuffled, and while lecturing he cleared his throat a bit too often to be considered mellifluous. I have learned not from Murray but from Greg Lange's chronology of his life and work that Murray was first published as a senior at Tacoma's Stadium High.

The title of his first work, "How to Second a Boxer" refers, I suspect, to Frank Sadler, a classmate who would sometimes win purses in out-of-town boxing matches away from his mother¹s scrutiny. Murray's recounting of how Sadler once broke up a military parade with his winnings was one the delightful stories that is here worth repeating, although not so well as Murray told it. Required to march in full uniform for the review of military brass, Sadler filled his pockets with small change won while boxing and through a hole in his pocket released the coins to the parade ground of Stadium Field as he and the forces passed in front of the review stand. Sadler's suspicion that the lure of free change would be irresistible to his fellow cadets was correct and the pomp and circumstance of the military review was soon reduced to a depression-time free for all.

Of the five books that came before Skid Road, two were novels. I recently read the second of these, The Viewless Winds, when the University of Oregon Press reissued it. Murray displayed a kind of mock pride when he recalled the novel's earlier distinction. The Viewless Winds sold a total of 242 copies when it was first published in 1949, stimulating the editor's claim that in 100 years of publishing never had a book sold less -- "not even poetry." Through nearly 70 years of publishing Murray delivered much more than his 20 or so books. It will now be the instructive pleasure -- perhaps for someone at the Tacoma Library -- to catalogue the thousands of articles and reviews he wrote for publications of all sorts. Eventually, we may hope for a "Murray Morgan Reader."

I met Murray when he was about the age I am now. I remember his 65th birthday, and not surprisingly, it seems more like nine years ago than nineteen. During the winter of 1979-1980, I helped Murray and his daughter Lane with the illustrations for their Seattle: A Pictorial History. Of the many delights that were attached to this friendship I must note one advantage. I was blessed to have recourse to a perfect reader, someone who was not only familiar with the subject but a friend who would gently help improve my writing.

The fondest memories are fixed upon the circle of friends gathered for dinner at the home at Trout Lake in southern King County that Rosa and Murray converted in 1947 from an old open-air dance hall. Dinner with the Morgans began in the late afternoon and often continued past midnight. It was here that the old stories were told and retold, stories like that of Sadler's "performance art" at Stadium High or stories about each other. Friends since grade school, Rosa and Murray had developed a helpful repartee that was often brilliant to witness.

During the summer this feast moved to Hartstene Island and the string of seven or so cabins -- some kerosene powered -- occupied by the Morgans and their friends. I photographed Murray in his Historic Murray Morgan teeshirt as he led me to a point at the north end of this beach collective.

There were, of course, other destinations, often the homes of other friends like Anne and Jim Faber. The dinner stories told about Jim and Murray's morning radio show and their muckraking through the politics of Tacoma in mid-50s were sufficiently hilarious to threaten digestion. The friendship I developed with Jim and Anne was a great delight, although short lived. Jim died in the late 1980s and Anne soon followed. The last time I talked with Murray we noted, as we had many times before, how much we missed them both.

Through the 1960s, Murray continued his radio reporting on Tacoma politics. As the opposite of an "Organization Man," Murray, of course, never ran for any political office. However, he and Rosa showed a somewhat heroic interest in politics that was both committed and reflective. Between the two of them through nearly 20 years of reporting they missed only a handful of Tacoma City Council Meetings.

Murray was thoroughly freelance. If the occasion required it, he could walk -- as he did from his position as head of the University of Puget Sound's journalism department when the school administration refused to reverse a ruling censoring a student journalist's criticism of the rising cost of coffee in the school cafeteria.

Earlier as a journalism student at the University of Washington, Murray was suspended for one day from his job as editor of the UW Daily for writing an article on the incidence of venereal disease on campus. There were about three cases. That time Murray did not resign, perhaps because Rosa, who was in charge of Daily photography and its library, was the only other paid staff member.

Since the publishing of Skid Row in 1951, The Dam in 1954, The Last Wilderness in 1955 and The Northwest Corner in 1962 most regional historians have been following Murray. He is the exemplar of the one who chose both his words and subjects well.

Although generous to a fault he was also a sharp parodist of pomp. By the mid-1960s, the still young Morgan was already the "Dean of Northwest Historians." A kind of "Morgan Standard" developed. A good deal of moral nerve and periods of at least the threat of poverty sustained it.

When Murray started producing his well-wrought histories, there were few others in the field. Now it is wonderfully crowded. I suspect that all historians -- popular and academic -- who treat on northwest subjects, will happily confess to have been following "The Historic Murray Morgan."

Ultimately, of course, all of us will catch up with him. The death of any good friend or cherished mentor is a reason for both calling on the support of fond memories and continuing with the resolve to live on.