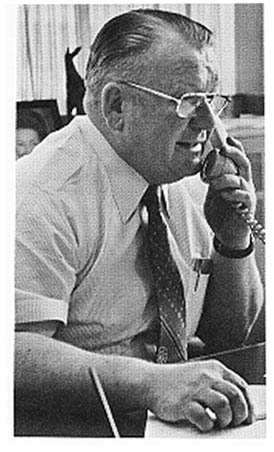

Gordon Franklin Vickery served the City of Seattle for 34 years, first as a firefighter, rising to the office of Chief, and then as Superintendent of Seattle City Light. In both offices he exercised strong leadership and implemented many innovations. His tenure at City Light was controversial and his impact on the department "had to be measured on the Richter Scale" (Watson). In 1977, both mayoral candidates promised to fire him. Vickery was born in 1920 in Ruthton, Minnesota, and moved to Snohomish with his parents. After his marriage to Frances Schluter (d. 1995) in 1941, he moved to Seattle. In 1946, he joined the Seattle Fire Department. He rose through the ranks and in 1963 was appointed Chief.

A National Model

Vickery built the Seattle Fire Department into a model for community service and fire prevention. His efforts to hire minorities and women won praise. When he donned the chief's helmet in 1963, Seattle had one African American firefighter. By 1972, there were 100 minorities in the department. He organized community safety programs and an arson task force, but his most visible achievement was Medic One.

In 1968, Chief Vickery began discussions with Dr. Leonard Cobb (d. 2023), Chief of Cardiology at Harborview, about providing care to heart attack victims at the scene. In 1970, the first unit of the pioneering Medic One became operational. This unit of the Seattle Fire Department provided out-of-hospital emergency cardiac care to heart attack patients.

Medic One involves both a system of reacting to heart attack emergencies and a custom-built van staffed by two specially trained firefighters and a physician. (After a time, the physicians communicated with the paramedics by telephone instead of riding in the car.) It was one of the first paramedic programs in the nation to provide physician-level assistance to cardiac patients at the scene of the heart attack.

Victims were first assisted by paramedics from a local Fire Department Aid Car who administered cardio-pulmonary resuscitation until the Medic One unit could respond from Harborview. In 1974, Medic One prompted the TV news program 60 Minutes to call Seattle "The Best Place to have a Heart Attack."

Power Trip

Vickery retired from the Fire Department in 1972, but immediately got a call from Mayor Wes Uhlman (b. 1935). The mayor needed someone to take over Seattle City Light, where there was "all kinds of nepotism, favoritism, wasted motion and goofing off" (Watson). Vickery accepted the challenge. He took the job and cracked down on extended lunch and coffee breaks, drinking on duty, favoritism for relatives, and employees taking tools home. He fired three-dozen employees, had others prosecuted for theft, suspended some supervisors, and cut the payroll from 2,000 to 1,750 employees. He increased minority employment at City Light from 6 percent to 10.5 percent. He placed women in administrative jobs and he instituted programmatic budgeting.

In 1974, City Light employees went on an 11-day wildcat strike to protest his management. The employees also launched a recall against Mayor Uhlman, which was defeated 2 to 1.

They Were Unhappy

When Vickery took the elevator to his office, City Light employees would get off rather than ride with him. His home and automobile were vandalized. A committee investigated his management of City Light. "The got me on one count," Vickery recounted. "The only thing they could find that was wrong about me was, 'Vickery doesn't get along well with employees' "(Watson).

When an ice storm crippled Portland one winter, Vickery ordered City Light crews to Oregon to help restore power. "Gosh," the old firefighter confessed. "I love an emergency" (The Seattle Times).

In 1977, mayoral candidates Charles Royer and Paul Schell both promised to fire Vickery if elected. Royer won, but he discovered that Vickery's contract permitted him to stay for his full term.

Nuclear Power v. Conserving Power

In 1975, Seattle was given the opportunity to participate in nuclear power plants being constructed by the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS). Vickery along with Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman supported the staff of City Light in need for the extra power (the Bonneville Power Administration placed considerable pressure on utilities to participate in the expensive plants), but environmentalists questioned the projections for power consumption and the advisability of nuclear power.

Vickery established a 27-member citizen's advisory committee, including environmentalists, to study the WPPSS matter and other City Light policies. Influenced in part by the Arab Oil Embargo and high oil prices, the committee reported, and the city council agreed, that additional power would not be needed if Seattle practiced conservation.

Vickery disagreed and called the move "a bum decision" (Chasen). Nevertheless, Seattle and City Light achieved savings with City Light's "Kill-a-Watt" program. Seattle ratepayers were not entirely spared the financial disaster of the multi-billion-dollar cost overruns and bond defaults that plagued WPPSS. They had to pay Seattle's share of the original investment ($50 million), but not the far higher tab it would have owed if Vickery had prevailed.

Federal Office

In 1978, U.S. Senator Warren G. Magnuson (1905-1989) nominated Vickery as the head of the U.S. Fire Administration under President Jimmy Carter (b. 1924). The agency was created to improve the nation's fire fighting capabilities. Under Vickery's five-year leadership beginning in 1979, the agency established the National Fire Academy, advanced fire-prevention education and a national fire incident reporting system, and Vickery worked for federal legislation requiring sprinkler systems and smoke detectors in buildings. He also served as the acting head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency in 1979.

Vickery returned to Seattle in 1984. He died of heart failure on December 14, 1996.

"I had one ruling credo," Vickery declared, "and I made it plain to the five mayors and the City Council people. 'I don't work for you,' I told them. 'I report to you, but I don't work for you.'

" 'I work for the city of Seattle' " (Watson).