This file contains Seattle historian and photographer Paul Dorpat's Now & Then photographs and reflections on The Great Depression and Seattle's shantytown of homeless and jobless people called Hooverville.

Hooverville

In the winter of 1934, University of Washington sociology student Donald Francis Roy paid $15 for a squatter’s shack set among hundreds of others a few blocks south of present-day (2004) Pioneer Square. Called Hooverville, this shantytown was home to hundreds of homeless men and a few women.

Hooverville was one of several shantytowns in King County inhabited by people who had fallen on hard times during the Great Depression. Another was "Louisville," located on Harbor Island, a conglomerate of shacks and huts populated by about 1000 residents in the dead of winter. Hundreds of similar sites dotted local tidelands, abandoned industrial parks, railroad sidings, and the banks of the Duwamish River.

Donald Francis Roy moved into Hooverville not to lighten the cost of housing but to write a master’s thesis titled "Hooverville, a Study of a Community of Homeless Men in Seattle."

Roy’s thesis is remarkable not only for its daring research, but also for its style. Since Roy completed it in 1935, it has influenced every bit of informed scholarship dealing with the effects of the Great Depression on the Pacific Northwest. The style is in turn sarcastic, playful, and sympathetic, and provides a profile of the author as well as of the inhabitants of Hooverville.

Roy writes of Hooverville: "From the sandy waste of an abandoned shipyard site ... was swiftly hammered and wired to flower a conglomerate of grotesque dwellings, a Christmas-mix assortment of American junk that stuck together in congested disarray like sea-soaked jetsam spewed on the beach. To honor a distinguished engineer and designer, this unblueprinted , tincanesque, archtecturaloid was named Hooverville." (Herbert Hoover, U. S. president from 1929-1933, was an engineer by profession.)

Before he could get started with his research, Roy’s $15 shack required some "aggressive adaptations." He placed "a curse upon the rat that gnawed under the flooring at night" and let go his assistant "who snored vigorously from 11 p.m. to 8 a.m."

His homemade stove leaked so badly that "one could quickly smoke a winter’s supply of fish." Roy vowed to get "an occasional night’s rest in an uptown hotel" and to eat one meal a day in a restaurant.

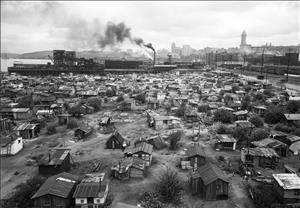

Our mid-1930s panorama of Donald Roy’s Hooverville was photographed from the roof of the B. F. Goodrich Rubber Company building at the northwest corner of (then) Connecticut Street and Railroad Avenue, today (1990s) named Royal Brougham Way and East Marginal Way. In this view we see a little more than half of the 500 shanties "scattered over the terrain in insane disorder … . In this labyrinth the investigator [writes Donald Roy] wondered for days, pacing off lengths and widths and distances from this to that and achieved, after a great sacrifice of leather, a fairly accurate map."

Roy used this map-making project to develop rapport with the residents. With the help of Hooverville’s mayor, a man named Jesse Jackson, he divided the shacktown into 12 lettered parts. Each residence was identified by a letter and number whitewashed beside the door.

With the "college boy’s map," the mayor explained, relief payments could be more readily delivered, new residents and drunk ones would have a better chance of finding their way home at night, and the residents could register to vote. Of course, the map would also help the "college boy" to begin his census and write his thesis.

Roy interviewed 650 residents. He developed a demographic profile of what he called "Mr. Hooverville, Seattle’s candidate for all-American oblivion."

Mr Hooverville was "jobless, propertyless, familyless. Savings spent, he came to Hooverville in the fall of 1932 to make that community his home." He was primarily a "rustler," scrounging for materials to build and maintain his shack and "bumming food from grocery stores." He was white, single, over 40 and a "shovel stiff" or unskilled laborer. Roy also counted seven women, 120 Filipinos, 25 Mexicans, and 29 blacks, one of them Hooverville’s "sheriff."

Roy noted that Hooverville was a rare social "air pocket" in which the normal impersonality of city living had not "choked out the flowers of open, unaffected friendliness toward fellow men. The spirit of camaraderie is carried over racial barriers. The attitudes of the Negroes, particularly, showed an utter absence of feelings of resentment or inferiority toward whites."

At the end of the 1930s, wartime prosperity and the expansion of shipbuilding brought the end of Hooverville. Many residents got jobs. Others simply moved up river and rustled new shacks. As for Donald Roy, he completed his thesis in 1935 and after that, the University of Washington has no record of what became of him.