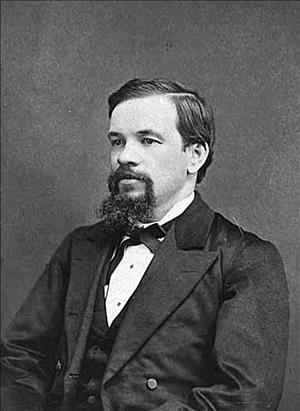

Thomas Burke, chief justice of the Washington State Supreme Court, arrived in Seattle in 1875 at the age of 25. A lawyer, he began practicing law, and within a couple of years was elected probate judge. He was a civic activist, becoming involved in education, railroading, and the cultural growth of the city. He opposed the Northern Pacific Railroad, became a partner in the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad, and in the end served as attorney for James J. Hill's Great Northern Railway to Seattle. He was an eloquent speaker and a voice for racial tolerance during the anti-Chinese riots of February 1886. He was married to Caroline McGilvra.

New York Irish

Burke was born in Clinton County, New York, on December 22, 1849, of strong Irish antecedents. After graduating from Ypsilanti Academy in Michigan, Burke read law with the encouragement of the Bagley family, who were friends of the Burkes. Soon after completing his studies, Burke was elected city attorney of Marshall, Michigan.

The Bagleys, both of whom were doctors, moved to Seattle in the 1870s. They invited Burke to try his wings in the Queen City of Puget Sound. Burke borrowed money for the trip and arrived by ship in 1875. Within a couple of years he had demonstrated his knowledge of the law and was elected probate judge. His law partners included several of Seattle's best lawyers, including Oliver C. McGilvra, son of Judge John J. McGilvra (1827-1903).

The Seattle Spirit

Besides his interest in the law, Burke became a champion of other projects, including higher education, railroads, and the cultural growth of his adopted city. He supported the University of Washington and Whitman College. Whitman conferred on him the LL.D. degree. His railroad interests hinged on connecting Puget Sound with Eastern Washington and points east, north, and south. In the cultural realm, Judge Burke embodied what became known as the "Seattle Spirit," endorsing and supporting history, literature, and art. He served on the board of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

On October 5, 1879, Judge Burke married Caroline E. McGilvra, daughter of Judge John J. McGilvra and Elizabeth (Hills) McGilvra. Caroline Burke also had civic and cultural interests. She worked on a food conservation campaign during World War I, participated in the Red Cross, supported the Ladies' Relief Society, Camp Fire Girls, the Seattle Garden Club, the Lighthouse for the Blind, and the Seattle Historical Society. Her social involvements included the Seattle Tennis Club, the Sunset Club, the Seattle Golf Club, and the Garden Club.

Opposing the methods and route of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Judge Burke and his partners incorporated the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway at Seattle in 1885. The new company planned to run a line from Seattle through Snoqualmie Pass to Walla Walla (a center of agriculture and at the time one of the state's largest cities), with a spur to Spokane Falls. Competition was stiff and potential financial support was often in the fickle hands of New York bankers. Also, railroads began to swallow each other and routes were contentious and subject to endless political bickering. Although the struggling Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern failed, Burke's heroic efforts were noted by James J. Hill, who retained him to help bring the Great Northern Railway into Seattle.

The Golden Gift of Eloquence

Judge Burke played a key role in calming Seattle during the anti-Chinese riots, which occurred in February 1886. Addressing a hostile audience, Burke called upon his considerable stump speaking abilities – one commentator said the Burke "had the golden gift of eloquence which has been likened to that of Patrick Henry" – to point out that minority rights must be respected. Burke also told his listeners that they should be concerned with the city's reputation. The riots were settled by cooler heads and by the intervention of the 14th U.S. Infantry.

Burke collapsed on December 4, 1925, while addressing the board of the Carnegie Endowment in New York City. Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University, caught him as he fell. He wrote that Burke died "in the midst of an eloquent and unfinished sentence which expressed the high ideals of international conduct."