On March 9, 1937, Seattle voters reject Proposition A to replace municipal streetcars (which run on tracks) with buses and the new "trackless trolleys" (rubber-tired vehicles powered by electricity delivered from overhead lines) at a cost of $11 million. The so-called Beeler Plan is opposed by Seattle Mayor John Dore (1881-1938), organized labor, and many reform and neighborhood groups. It fails by a vote of 59,000 to 39,000. This provides only a brief reprieve for the street railways, which are dismantled by 1941.

Beginning in 1884, Seattle's street railway system had been built up incrementally by private entrepreneurs and real estate developers. In 1898, agents of the national Stone & Webster utility cartel began buying up all of the city's 22 independent streetcar lines. Despite fears of monopoly control, in 1900 the City of Seattle granted Stone & Webster's Seattle Electric Railway a 40-year franchise.

Nickeled and Dimed to Death

But by World War I, the system was losing money due to the nickel fares mandated by the city franchise, lack of capital for improvements, and growing labor unrest. Mayor Ole Hanson (1874-1940) negotiated the city's purchase of the street railways for $15 million, and voters approved the purchase on November 15, 1918.

Buyer's regret set in almost immediately, when people realized that the price was three times the system's true value. A grand jury investigated the deal and found the mayor guilty of "stupidity," but not graft. The debt drained resources from the streetcars, and a 1922 State Supreme Court ruling blocked any city subsidy beyond fare revenues.

Low Politics, High Finance

Stone & Webster's main local company, Puget Sound Power & Light, manipulated the city's problems in an attempt to take over Seattle City Light. The street railway's chronic woes contributed to the defeat of Mayor Bertha K. Landes (1868-1943) in 1928 and to the recall of her successor, Frank Edwards, two years later. Local efforts to refinance streetcar debt failed repeatedly, in part because national automakers such as General Motors pressured major bond houses to decline assistance.

By 1936, the municipal street railway was operating 410 streetcars on 26 electric routes as well as three cable car lines totaling 231 miles of track. The city also operated 60 gasoline-powered buses on 18 additional routes. Despite average daily revenues of $11,000, the system had run up an operating deficit of $4 million and had paid down less than half of the principal on the original purchase price.

Off Track Betting

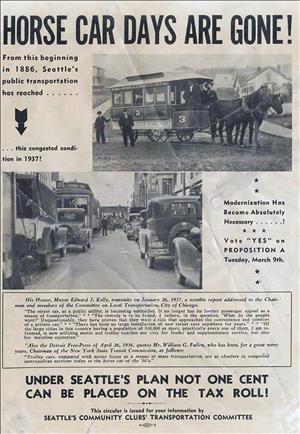

Seattle retained the engineering firm of John C. Beeler to explore alternatives, but rejected its first plan for a rail-bus system. The Beeler Organization responded with a revised plan that scrapped streetcars for a combination of buses and new "trackless trolleys."

These electric buses had been first introduced in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1928, and later in Portland, Oregon. They did not require expensive rails and could pull up to the curb, unlike streetcars, which loaded and unloaded passengers in the center of the street. To answer skepticism over the new vehicles' power, Beeler staged a race up Queen Anne Hill's "counterbalance" between a streetcar and a trackless trolley. The trackless wonder won easily.

The City Council placed the Beeler Plan on the March 9, 1937 ballot in the form of Proposition A, which proposed $11.6 million in bonds to finance the conversion and settle the streetcar debt. The plan was opposed by Mayor John Dore, the Amalgamated Transit Union and other unions, by the Municipal League, and by many neighborhoods that feared loss of transit service. Despite a terrible streetcar accident in West Seattle two months before the election, the Beeler Plan failed by a vote of 53,000 to 39,000.

A Pyrrhic Victory

The street railway could not take its victory to the bank, however, and its financial situation got so bad that the city had to pay employees with nickels and dimes straight from the fare box. Mayor Dore died amid the crisis on April 18, 1938, and his successor, Arthur Langlie (1900-1966), immediately turned to the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) for an emergency loan. (Ironically, Langlie was a Republican appealing to a Democratically-controlled New Deal agency.)

An RFC loan for $10 million was approved in May 1939 to pay off the Puget Power mortgage (antitrust regulators had broken up Stone & Webster in 1934, and Puget Power was reorganized under local control), and implement the Beeler Plan. The State Legislature also mandated creation of an independent Seattle Transportation Commission to manage the new system. The conversion to buses and trackless trolleys began immediately.

The last Seattle streetcar completed its run on April 13, 1941.