On March 11, 1958, voters in western King County reject creation of a new government agency, the Muncipality of Metropolitan Seattle, with broad responsibilities for regional sewage treatment, public transportation, and regional planning. A narrower Metro plan for improving water quality was adopted the following September. (Metro took over regional transit in 1972 and was merged with King County in 1994.)

Impending Crisis

The idea for a new, federated city-county agency to tackle regional issues such as waste management, mass transit, regional parks, and regional planning was inspired in part by progressive reformers' frustration with King County government, which they viewed as corrupt and unresponsive. They also saw mounting problems due to growth and suburban sprawl, including traffic congestion, pollution, deforestation, and other threats to the area's quality of life.

Reformers led by the Municipal League of Seattle and King County doubted if the county's 180 independent jurisdictions could muster the consensus and authority to cope with these needs. Their first solution was to restructure King County government under a new home rule charter, but opponents denounced the plan as too radical, even Communistic, and voters rejected it in 1952.

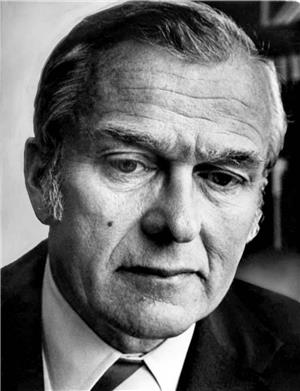

The following year, James R. Ellis (b. 1921), a young attorney and leading proponent of the unsuccessful effort to enact a new charter, addressed the Municipal League on the impending crisis in regional governance and growth. The League created a special committee chaired by John Blankinship and later C. Carey Donworth to study regional needs and solutions. Its 1956 report prompted Governor Arthur Langlie (1900-1966) to appoint a special state committee on metropolitan problems. In addition, the King County Board of Commissioners and Seattle Mayor Gordon Clinton (1920-2011) appointed Ellis to chair a local Metropolitan Problems Advisory Committee.

A New Approach

Inspired by the metropolitan government of Toronto, Ontario, Ellis and his committee drew up a plan for a new "federated" municipal corporation to be governed by representatives of King County and local governments. It would act much like a public utility to provide regional, cross-jurisdictional services such as waste treatment, mass transit, regional parks, and long-range planning, while being shielded from direct electoral politics.

The Ellis committee drafted enabling legislation and sent it to Olympia, where it faced withering opposition from conservatives and rural and suburban communities, which feared the precedent of local "supergovernments." Democratic State Senator Robert R. Grieve and Republican Senator William Goodloe joined forces to get the law passed in the upper chamber, while freshman Republican Representative Daniel J. Evans helped in the House. Thanks to an adroit maneuver by House Speaker John L. O'Brien, the Metro act passed by a single vote on the last day of the 1957 session. Newly elected Governor Albert Rosellini (1910-2011) promptly signed the bill into law.

The original Metro boundaries were drawn to embrace King County's most populous western areas (it became coterminous with King County with passage of Metro Transit in 1972). The first Metro plan asked for local authority and funding to improve waste treatment, water quality, mass transit, and comprehensive planning. Of these needs, stopping the flow of inadequately treated sewage into Lake Washington was the most urgent, but development of a mass transit system to contain suburban sprawl and traffic congestion was closest to reformers' hearts.

Opposition and Recovery

Lawyer Nick Maffeo attacked Metro as undemocratic and led opponents around Renton and in south King County. Metro also met criticism in Eastside suburbs such as Kirkland, which had invested heavily in their own sewage treatment plants. Metro's approval required dual majorities in Seattle proper and in the rest of its service district. On March 11, 1958, Seattle voters approved Metro by a 3-to-2 ratio and the measure won an overall majority, but the plan was killed because it narrowly missed a majority in the suburbs.

Metro backers regrouped by redrawing the boundaries to exclude the more recalcitrant South County precincts and by focusing on the most visible problem, the poisoning of Lake Washington and other local waters with human and industrial waste. Mayor Clinton also made concessions that helped to mollify Eastside communities. The revised plan carried Seattle easily on September 9, 1958, and it won by an even larger margin outside the city.

Metro had made substantial progress in cleaning up Lake Washington by 1964, with the successful cleanup effort continuing in subsequent years. It expanded countywide in 1972 when voters gave it authority for a regional bus system.

In 1990, Federal District Judge William Dwyer (1929-2002) found Metro's federated Council membership to be unconstitutional. In 1992, voters approved its merger with King County. Two years later the agency ceased to exist.