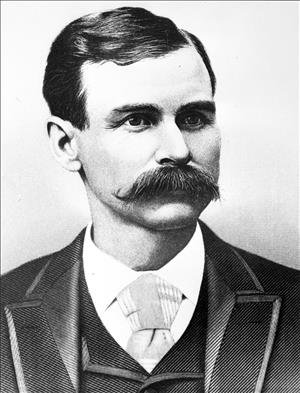

On July 14, 1890, voters elect Republican Harry White as Mayor of the City of Seattle. He is the last mayor elected under the city charter adopted by the Territorial Legislature in 1869 and the first to serve under a new “home rule” charter, approved by Seattle voters on October 1, 1890. He resigns, under pressure, four months before the end of his two-year term.

White, a native of Iowa, moved to Seattle in 1887 and quickly rose to prominence as a real estate investor. He platted and developed dozens of neighborhoods in Seattle, West Seattle, and Kirkland. He also invested in mining properties, principally in Alaska. In one reflection of his standing in the community, he was elected to a one-year term on the Common Council in 1889, just two years after arriving in Seattle.

When White took office as mayor on August 3, 1890, the city was still struggling with the aftermath of the Great Fire that had destroyed much of the downtown area one year earlier. Streets, wharves, sidewalks, and sewers in the lower part of the city had been rebuilt; the grades of business streets had been raised; several streets had been widened, graded, and planked; and steps had been taken to improve the municipal water system. However, most of the bills for this had not been paid. The city’s net indebtedness stood at more than $312,000, compared to $44,000 right before the fire.

The new mayor also faced considerable challenges as a result of changes in the city government. When Washington became a state on November 11, 1889, Seattle became eligible for a “home rule” city charter, written by Freeholders (temporary officials elected to draft city and county charters subject to public ratification.) Under the Freeholders Charter of 1890, what had been a small, largely volunteer city government gave way to a much larger, more complex operation. The charter extended the mayor’s term of office from one year to two, created numerous new municipal departments and offices, and changed the date of the general election from July to March. It also greatly expanded the size of the city council, by introducing a bicameral legislative body of eight aldermen and 16 delegates.

To accommodate the larger council, White recommended that the city buy the old County Courthouse at 3rd Avenue and Jefferson Street. He pointed out that the city was already paying $500 a month rent for office space and still did not have regular meeting rooms for many of its new boards and commissions. The old courthouse, he added, could house both a fire station on the ground floor and a jail in the basement. The city bought the building at an auction, for $61,000, on June 13, 1891.

White eventually came under criticism for his management of municipal affairs and he was forced to resign. He left office on November 30, 1891. The city council appointed George Hall, also a Republican, to complete the remaining four months of White’s term.

White continued living in Seattle for a number of years, although he never returned to public life. His investments in mining properties and oil lands in Alaska apparently made him quite wealthy. By 1916, he was living in Los Angeles and managing his investments through offices in Seattle and London.

Clarence B. Bagley, a contemporary of White’s, both lacerated and praised the former mayor in his three-volume history of Seattle, published in 1916. “While Mayor Harry White and the first city council, under the new charter…held office, extravagance ran riot, debauchery and crime were almost unchecked,” he wrote at one point. “Gambling of every known variety flourished openly, as did harlotry and drunkenness, under the fostering eyes of the police” (Vol. 2, p. 549).

Yet later, Bagley credited White with widening and regrading the streets, relocating the railroad tracks, developing a municipally owned water system, laying out parks and boulevards, promoting the public library, and otherwise rebuilding Seattle “along modern, progressive lines.” In sum, “The story of Seattle’s advancement since 1889 without mention of Mr. White would be like the play of Hamlet without the appearance of the Danish prince” (Vol. 3, p. 1141).