The Seattle Union Record, published from 1899 to 1928, was labor's voice in the Pacific Northwest for nearly 30 years, reaching a peak circulation of 80,000, and achieving its greatest fame during the 1919 Seattle General Strike. The paper was owned by the Central Labor Council of Seattle (predecessor to King County Labor Council), and was edited for much of its existence by Harry B. Ault (1883-1961). The weekly Union Record became a daily paper on April 24, 1918, and ceased publication after 28 years in 1928.

Not in the Interest of Economic Privilege

"Journalism in America is the business and practice of presenting the news of the day in the interest of economic privilege," observed hell-raiser Upton Sinclair. Efforts to do the opposite -- present the news of the day in the interest of labor -- resulted in a proliferation of labor related publications in the early decades of the twentieth century. Some were weeklies, others were dailies. The average life span of the dailies was seven years. The Seattle Union Record, published as a daily for its last 10 years, outlived the average daily labor paper by three years. Among all the labor newspapers, it was the only one owned by an American Federation of Labor (AFL) affiliated central labor body in a metropolitan area.

It all started at a December 20, 1899, meeting of the Western Central Labor Union (reorganized in 1905 as the Central Labor Council of Seattle, which was predecessor to the King County Labor Council). The body approved a proposal to publish a labor paper in Seattle. The Union Record first appeared in 1900 as a private venture under the editorship of Gordon Rice, who had edited the short-lived Labor Gazette in 1894.

In March 1903, the Western Central Labor Union bought the Union Record for $350, made it the official organ of the central body, and elected a six person board of control, keeping Rice as editor with a salary of $40 a week. Frank Rust, a unionist of noted integrity and conservative business ability, was made general manager.

The Man Who Made the Union Record

Without Harry Ault in the Seattle labor movement, there may never have been a Union Record. It was his personal achievement, as well as failure. It was his aim to make a top level paper, but it was a paper owned by an organization, and he was obliged to use writers from the larger member unions. Some of these writers wrote poorly and too avidly, thus hurting the paper. It wasn't completely in Ault's control.

Ault, born October 23, 1883, in Newport, Kentucky, a Cincinnati suburb, was the first of seven children. He claimed to be "the First American-born Socialist born to an American-born Socialist" (O'Connell, 15). Naturally, the family was poor. At five, Ault was selling the Kentucky Post. At 11 he had established his own paper, the Amateur's Friend. The next year he was hawking the Socialist Party's Weekly People on the streets of Cincinnati.

When Ault was 14 his family moved to the Socialist colony, called Equality, being established near Edison, Washington, on Rosario Strait in Skagit County. By the time the spirit of brotherly love and sacrifice was overshadowed by petty jealousies and selfishness, and the community had died, Harry had become a newspaper man.

First he published The Young Socialist, which he financed by rowing a boatload of scrap-iron north to Bellingham and selling it there. In 1903, at 19, he became editor of The Socialist in Seattle. The Socialist was published by Dr. Hermon Titus, a graduate of a New York theological seminary and an M.D. from Harvard.

After working a while for an Idaho socialist paper, Ault returned to The Socialist, where he earned $3.50 a week. In 1910, as a delegate from the Typographers' union, Ault was elected secretary of the Central Labor Council of Seattle. In 1912, at the age of 28, he was chosen to edit the Central Labor Council's weekly organ, the Union Record. Circulation was about 3,000 at the time. According to Ault, this was the job he had been looking for all his life in his passage from one reformist or revolutionary publication to another. His dream was to make the Union Record a dynamic, labor-owned daily.

New Era of Labor Journalism

The paper was never financially strong. Some unions objected to an assessment on all affiliated locals by dropping out of the Central Labor Council. An employer organization, the Citizens' Alliance, urged local businesses to withhold advertising patronage. In summer of 1917, the paper was kept alive only by donations.

In 1917, Ault began a campaign for individual subscriptions among workers earning war wages, higher wages than ever before. By 1918, circulation had increased to 25,000 copies -- home delivered. He also started a Trail Blazers Fund for a daily Union Record. Conservative unionists objected, foreseeing great difficulty in maintaining such an operation.

Ault's response was that the labor movement urgently needed a daily press of its own because the "kept press" was completely subservient to city and national business interests. To support his position, he could have, but apparently didn't, quote Henry Clay Frick, Carnegie Steel manager, who said to his secretary after glancing at an offending cartoon of himself, "This won't do. This won't do at all. Find out who owns this paper and buy it" (O'Connell, 27).

In an autumn 1917 edition, Ault wrote what was on his mind:

"The Union Record will help you win a greater prosperity ... . The Union Record is the only paper in Seattle that dares be consistent in its fight for the working man. It is opposed to capitalist control of the legislative, judicial and executive branches of government. It gives you all the news the other papers give, and, in addition, the news the other papers will not print. It is the one paper that stands between you and industrial slavery ... ." (O'Connell, 27).

On April 24, 1918, the Union Record became the Daily Union Record. Ault had raised more than $13,000, gained 20,000 trial two-month subscriptions, and talked another small Socialist paper, the Seattle Daily Call, also struggling, to quit business so the daily Union Record could benefit by picking up some of its readership. The paper was incorporated as a stock company, with 51 percent of the common stock held by the Central Labor Council. It was hoped that people understood that they were buying stock not for personal profit but as an investment in the future prosperity of the working force.

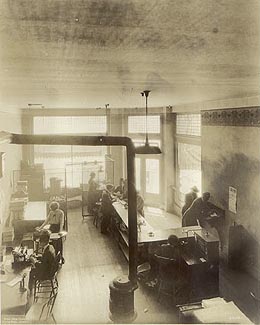

After a struggle to arrange a press association (UPA) contract, Ault had to find a plant for the publication. Seattle's Labor Temple, then at 6th Avenue and University Street, was inadequate and inappropriate. A block away on the northeast corner of 6th Avenue and Union Street, he found space. Soon a sign lettered in white with green outline read

Seattle Union Record

Published for Principle and not for Profit

Although other Seattle papers took no editorial notice, a battle over circulation began in earnest. As Ault later described it to the Director of the Industrial Division of the United States Children's Bureau: "A monopoly privilege to sell newspapers on certain corners, secured, through force, squatter sovereignty, barter and other means ... [grew] to such an extent that one young man 'owned' approximately 40 corners, from each of which he took one/half the net profits" (Letter, November 20, 1920, quoted in O'Connell, 38).

To counter the establishment's actions, the Union Record promoted the revolt of about 300 newsboys and the organization of one of the first Newsboys' union in the United States.

Anna Louise Strong

During the first three years of the Union Record's life, a chief influence was Anna Louise Strong (1885-1970). Strong, the daughter of the local Congregational minister, received her B.A. from Oberlin in 1905 and her Ph.D from University of Chicago in 1908. She had been elected to the Seattle School Board as a progressive and, thanks to opposition of mainstream media (particularly The Seattle Times) had been recalled as too radical.

Under Strong's leadership, in May 1918, the Union Record swung into battle for the Western Union employees, "the telegraph girls," who had been locked out in defiance of a government ruling in their favor after they formed a union.

In April 1918, Strong wrote the foreword to the Union Record publication (20,000 copies sold out, 20,000 more in Canada) of Lenin's address to the Congress of Soviets.

Other Sorties

In the spring of 1918, the Union Record took on the authorities who closed the local IWW hall, arresting 206 men attending a lecture entitled "How American Justice Works." The discovery of draft-dodgers or "slackers" was the ostensible purpose of the mass arrest.

Next, during this war year, the paper took on the rich in Seattle with a headline: "SEATTLE RICH NOT OBSERVING ORDER TO WORK OR FIGHT." The article noted the presence of "autos of wealthy people" parked in the shopping district "with the usual able-bodied male chauffeur at the wheel."

The paper kept up a campaign for public utilities to replace the corporations of the "interests."

During the Tom Mooney trial in San Francisco in autumn 1918, the Union Record gave nearly a page a day to full blow-by-blow trial coverage. (Tom Mooney [1882-1942] was a socialist union organizer convicted of murder in connection with a 1916 bomb explosion in San Francisco. Nationwide protests over his conviction lasted two decades, and a 1931 report by the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement cast serious doubt on the evidence that led to his conviction. He was pardoned in 1939.)

A Turning Point

The Seattle General Strike of 1919, which closed down the city for four days beginning on February 8, 1919, had a tremendous impact on the future of the Seattle Union Record. While the paper had successfully moved from a weekly to a daily, had covered many key movements in the city, had fought off considerable opposition, it had not managed to keep the propaganda confined to the back page as Ault had promised (a false promise at best, no matter who makes it).

When it came to event leading up to the General Strike and the strike itself, an impossible situation, in terms of journalistic objectivity, existed. Ault, in his editorials, always wrote responsibly. Anna Louise Strong was less realistic and tempered only by libel-conscious editors.

The General Strike probably had the same effect on the Union Record that it had on labor in general in Seattle. The immediate effect was a boost in circulation, eventually up to 80,000 subscribers, with their papers printed on the Union Record's one ancient press. But, recriminations and hostility ran deep and wide against the strike, the strikers, the labor movement, and the voice of the Central Labor Council -- the Union Record. Internecine conflicts turned Central Labor Council meetings into a weekly uproar.

Moving Toward the End

By 1920, Ault began to recognize the truth, as Oscar Ameringer of the Oklahoma Leader put it, that "Running a labor paper is like feeding melting butter on the end of a hot awl to an infuriated wildcat" (O'Connell, 49). The Union Record had been launched on the crest of labor strength and wealth in the Pacific Northwest. These conditions did not prevail for long. The loss of class consciousness by Seattle workers after the General Strike and the schisms in the labor movement compounded the inherent financial difficulties of the Union Record and led it to seek release from union ownership.

The end came in early 1928, after several years of struggle. The first issue of the daily Union Record sounded of war in Europe and labor struggles at home. The last issue reflected a hectic kind of peace. The headlines in the first issue were sensational. Those in the last issue catered to a taste for different sensations such as: FILM STAR SCALDED IN ROW MUST QUIT SCREEN -- LINDY FLYING HIS OLD ROUTE -- 12 MISSING IN TRAGEDY OF SF BAY FERRYBOAT. The maiden issue of the daily on April 24, 1918, carried an editorial announcing WHY WE ARE HERE. The last front-page editorial on February 18, 1928, was headed simply THIRTY.

The Union Record name was briefly revived in late 2000, when members of the Pacific Northwest Newspaper Guild on strike from The Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published 18 print editions (plus, in keeping with the technological advances of the intervening decades, a website) of a newspaper they called the Seattle Union Record after its labor forebear.